State's Prisons Exploding

NOV. 5, 2010

By ANTHONY PIGNATARO

It was apparently a matter of “disrespect.” It happened at Calipatria State Prison, located on the edge of the Salton Sea near the Mexican border. Around 2 p.m. on June 12, two inmates met at the Facility A recreation yard and shortly thereafter began fighting. In no time at all, the fight escalated into a riot involving 39 inmates, 37 of whom were injured. One inmate, S. Johnson, later died. “It was something small that grew into something big,” prison spokesman Lt. Jorge Santana said. “That’s prison.”

Four months later, on Oct. 19, another riot broke out at Calipatria’s Facility A. This time, 120 inmates battled each other. Staff eventually busted up the riot with a combination of pepper spray and Mini-14 rounds, injuring 14 inmates. That riot, though still under investigation, is not believed to be linked to the June 12 violence, Santana said.

Over the last six months, riots and other acts of disorder have broken out at seven prisons, all over the state. On July 9, racial tensions at the California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison at Corcoran led to an inmate work stoppage and hunger strike. Two weeks later, one inmate stabbed another inmate to death in the San Quentin reception center yard (the murder is still under investigation, a prison spokesman said). On Aug. 27, 200 inmates rioted at Folsom State Prison, just outside of Sacramento. There, guards used “verbal orders, chemical agents, less-lethal ammunition and deadly force options [read: bullets]” to quell the violence, according to prison spokesman Lt. Anthony Gentile. A month later, an inmate at High Desert State Prison in Susanville who tried to kill another inmate was himself shot and killed by guards. Nine days before the second Calipatria riot, a dozen inmates at the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco rioted.

Though corrections officials deny that these incidents illustrate a trend, they do exemplify the tinderbox-like state of California’s prison system. In fact, as late as last year, researchers began noting the rising violence. They especially found troubling a massive riot on Aug. 8, 2009 at the California Institute of Men in Chino. That riot, which prison officials later said stemmed from “racial tensions,” involved more than a thousand inmates (249 of which were injured). Nine prison guards also sustained injuries and inmates burned seven dorm units. No one died, but damage costs ran into the millions. Race also apparently played a role in a smaller May 21, 2009 riot at the Chino prison.

“The problem in the Golden State is not the overall rate of prison inmates per capita (we are average when compared with other states) but overcrowding,” Professors Robert Weisberg and Joan Petersilia wrote in the Oct. 23, 2009 issue of the Stanford Lawyer (Petersilia declined to comment for this story, but sent a copy of the article). “Where we do see upheavals, like the one in Chino, they usually are not organized as rebellions against authority – except in the indirect sense that the physical and psychological pressures of state-tolerated overcrowding make daily wear-and-tear tensions among prisoners all the more volatile.”

Indeed, a day after the Folsom Prison riot, Lt. Gentile told reporters that the riot “just seemed to explode.” It then took 30 minutes for guards to stop the violence.

“There’s no question about it,” Donald Spector of the Prison Law Office, which has advocated on behalf of prisoners since 1976, said when asked if there’s a link between overcrowded prisons and violence. “California prisons have been overcrowded for so long it’s hard to figure out what normal is anymore. They’re overcrowded because of sentencing laws and parole laws that put more people into prison than they were designed for. We can change those laws, but the state hasn’t done that.”

All of the prisons that have seen violence since June are experiencing horrendous overcrowding – state corrections figures show inmate levels between 139 percent and 202 percent of design capacity. The state built Calipatria in 1992, which saw two riots this year, to incarcerate 2,208 inmates but it’s currently holding 4,272 – an overcapacity rate of 193 percent. Folsom, the second oldest prison in California, should only be holding 2,085 prisoners; it has 3,540. Chino, ironically enough considering the violence that plagued the institution in 2009, has just a 139 percent occupancy rate.

Santana, Calipatria’s spokesman, said he didn’t think the recent violence was any more than usual for the prison. “Incidents as a total were pretty much the same as last year,” he said, though he added that he couldn’t remember any riots in 2009. “In the past five years, violence has gone down,” he added.

Though Weisberg and Petersilia say that prison riots have become “less common in the United States in recent decades,” they also made clear that riots “are a problem demanding attention on their own.” This is because California’s unique overcrowding conditions actually make the potential for more prison riots more likely. Specifically, they took notice that Chino’s riot began in its “reception area.”

“At any time, a large fraction of prisoners are in open double- and triple-bunked dormitories where new prisoners live while awaiting long-term designation (think 600 high school students sleeping and hanging around for weeks in the gym),” Weisberg and Petersilia wrote. “These reception centers can be a managerial nightmare. The physical environment is very hard to secure and, worse yet, there populations are often a chaos of inflow and outflow… Under these circumstances, the most able and fair-minded prison administrator finds it difficult to provide security and order, and it is sometimes the prison riot that provides public confirmation of that difficulty.”

Race — which causes tension in civil society — poses special dangers in the densely packed prisons. The work stoppage at the California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison at Corcoron (currently operating at 187 percent of capacity) in July was a result of attempts by prison officials to integrate a few new northern Hispanic prisoners in with the facility’s southern Hispanic population.

“At the time, there were no northern Hispanics in the facility,” prison spokesman Lt. Stephen Smith said. “You have to be careful with that — northern and southern Hispanics typically have issues.”

Of course, the knowledge that California’s prisons are overcrowded is old news. Over the past few years, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger has floated various ideas – moving female inmates to “community detention centers,” early releases of other inmates, transferring a few thousand more inmates to county jails and passing a few billion in bond measures to boot.

A panel of three federal judges also ruled in 2009 that California’s overcrowding is so bad prisoners can’t get sufficient medical care – a violation of the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Their order to release 46,000 inmates is currently under review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the meantime, advocates like Spector see more work ahead of them. When asked if he’s getting more inquiries these days for legal help, Spector said there was no question. “We’re now receiving hundreds of letters per day,” he said.

Photo of San Quentin State Prison courtesy of State Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Related Articles

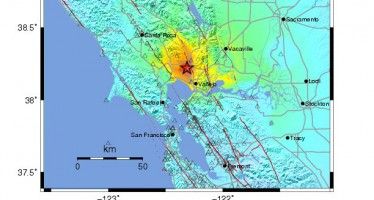

Expert says drought did not cause Napa quake

Natural disasters predictably bring up speculation about causes. On radio shows, callers have been wondering whether the ongoing drought or

Will Enviros Bend on CEQA Reform?

Jan. 28, 2012 CEQA, the California Environmental Quality Act, has long been the third rail of politics here in theGoldenState.

High speed rail pushed back 4 more years

Falling short even of some critics’ expectations, California’s beleaguered high-speed rail was dealt another blow to its credibility as