Gov. Brown should get Esquire’s Dubious Achievement Award

By Wayne Lusvardi

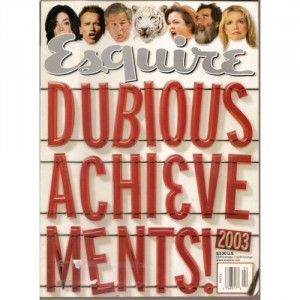

Esquire magazine once gave out an annual Dubious Achievement Awards as a running gag for unintentional humor, but discontinued it in 2008. Esquire should revive and give it to Gov. Jerry Brown’ for his interview, titled “What I’ve Learned,” in its November issue.

Brown’s interview was not a direct pitch for his tax increase proposal on the November 6 election ballot, Proposition 30. Instead, Brown and his public relations handlers tried to project a slick image of coolness and hip moral superiority. They hoped this would impress jet set college age voters who read Esquire to indirectly consider voting for Brown’s tax increase by identifying with his countercultural lifestyle and values. And what better person could there be to create an image with the youth culture than Brown, who never entirely left that culture himself?

Brown’s answers to interview questions seem highly scripted by political handlers to give young, idealistic and impressionable voters what they want to hear. Wat else can we call Brown’s interview but unintended humor?

Let’s consider how dubious Brown’s interview statements with Esquire are.

Brown: “There’s not a difficulty to having an insider’s knowledge and an outsider’s mind. The more you understand, the better off you are.”

When Brown came into government in the 1970s, he was considered an outsider who wanted to communicate he wasn’t the typical duplicitous politician put where he was by big corporate interests. He never lived in the governor’s mansion. He embraced the counterculture, dated pop singer Linda Ronstadt, and hung out at antiestablishment nightclubs and restaurants. He wanted everyone to know he wasn’t into money; that he was different than other politicians because he was spiritual.

But after serving two terms as governor, we found out he was just like everyone else — a slick politician. He was better at what former U.C. Berkeley sociologist Irving Goffman called “impression management” than he was at managing any accomplishments.

In fact, he prided himself in not accomplishing anything. Psychologists call this passive aggressiveness. His accomplishments were all negative: He stopped all new freeway development; replaced new power plants with building energy regulations that ended up causing “sick building syndrome”; appointed Supreme Court judges that the public had to kick from office; signed into law lucrative pension packages that are now bankrupting cities; delayed the airborne spraying of malathion to squelch the spread of medflies resulting in millions of dollars of crop losses; tilted court procedures in favor of defendants that resulted in voters’ retaliating with the Three Strikes Law; and he opposed Proposition 13 — then supported it after it passed. Brown was an outsider all right: he didn’t understand how to govern.

Cherry tree

Brown: “I have a cherry tree right below my deck at home. In the spring, the cherry tree has these beautiful white blossoms. Then cherries appear. Then everything falls off and the limbs have a whitish appearance. It looks like the tree is dead. But I know in a few months the blossoms will come again. And I find it somewhat encouraging that there is renewal amidst all this other stuff we’re encountering in the political realm.”

One must ask Brown: Where is the economic renewal for California after five years of managed depression, including his first two years in office? Brown tends to believe that everything will be OK on its own. But even cherry trees need certain nutrients to thrive.

In California, government makes it so difficult for small businesses that they often die. Their demise isn’t only because of the after effects of the Mortgage Meltdown. It is also because of regulations that have no demonstrable benefit to the public: such as perchlorate regulation or Cap and Trade used as a wealth distribution scheme. The Mexican or Turkish grocer who moves to California with the hope of one day owning and operating a supermarket better forget such dreams under a Jerry Brown’s anti-business governorship. Unlike George Washington, Brown should receive the “dubious achievement” award for chopping donw the cherry tree.

Brown: “It was the mysticism, the otherworldly quality that drew me toward the priesthood…. I think I’m the only governor that has actually taken vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. These were perpetual vows–even though the pope released me from their obligation when I left the Jesuit order. But there is an experience there. Austerity is something of real value.”

Asceticism — a life of self-denial and austerity — has been historically used to give moral authority to traditionalism, nationalism, socialism, and postmodernism. Cesar Chavez was a California Catholic farm labor movement organizer. Chavez went on long fasts to gain moral authority for his cause.

Gandhi was an Indian nationalist and pacifist who took a vow of poverty. Lenin was a Communist revolutionary and mass murderer who adopted a life of asceticism. Jerry Brown uses the façade of an ascetic, monk-like life style to gain moral authority for his postmodernist political ideology. There is nothing inherently more moral with austerity. It is a tool that can be used to make any political end or system seem morally superior.

Jerry Brown is probably California’s wealthiest governor ever. He has an undisclosed fortune in an oil trading company he inherited from his father, former Gov. Pat Brown. An oil trading company in Hong Kong was given to Brown Sr. by Indonesian generals who took over their country in a violent coup. This was in return for Brown Sr. brokering $12 billion in U.S. loans to help nationalize oil companies. Brown Jr.’s inherited business was lucrative because Indonesian low-sulfur crude oil could meet early clean air standards in California.

Brown can choose to live an austere lifestyle where others can’t. He is married to Ann Gust, former chief administrative office of the Gap, a chain of youth culture clothing stores. The Browns maintained a home in the Oakland Hills bought for $1.8 million, according to the Huffington Post.

Like everything else about Brown, you never get full disclosure about who he is or what he really stands for. Is Brown’s lifestyle simplicity or duplicity?

Jerry knows Latin

Brown: “There is this notion captured by the phrase tantum quantum in Latin. What that stands for is: So much, how much. So much you need, that’s how much you should get. That’s the principle. I’m not saying I come close to that. But it’s an ideal. Our system of economy doesn’t work that way. The notion of capitalism is the endless creation of new needs and desires. Then the fulfillment of those needs and desires by a proliferation of novelties, commodities, and new services. So the whole system depends on the opposite of tantum quantum. Now, how long and how stable that system is, that’s another question. When people want less of taxes and more of everything else, you’ve got a problem.”

Can even young impressionable people take Brown’s above statements seriously? He conveys an unbelievable ignorance of how our capitalist economy and representative form of government work. In fact, he portrays our system in reverse of the way it is supposed to work: it is when people are able to earn more of everything else that more taxes are generated. And lower tax rates have historically led to more economic productivity. In fact, much of the state general fund budget relies on capital gains taxes on profits made from stocks and real estate.

Brown is a postmodernist who wants to go back to 19th century technologies: trains, barges, windmills, and water wheels modernized for greater efficiency. They may clean the air but kill the economy.

Roman republic

Brown: I’ve been reviewing the history of the late Roman republic, and I found that the struggles between the senators — or what were called the optimates versus the populares — were endless and often violent. Some senators lined up with the masses. Others were more conservative and upheld the traditions of the elite and the old families. These struggles got more and more violent, and ultimately it all broke down. It seems like the nature of a republic is that there is a lot of struggle. That’s just the way it is…. Looking back, what I appreciate is the stability of these larger institutions, or their inertia–they move very slowly. Whether you’re trying to change a school system or a political party or some bureaucratic aspect of government, things just move relatively slowly. Absent a crisis, you can only nudge them. The people elected for four years or eight years are bit players.”

The Optimates in the Roman Republic were a corrupt social class that advocated collective rule by the Roman Senate. The Populares were an equally corrupt class of aristocrats who formed a coalition with the Plebians for their own self-serving aims. As documented in Klaus Bringmann’s, “A History of the Roman Republic,” those who were offered free land to become Roman soldiers ended up robbed by Populare tax farmers and sold into slavery. But Brown is not likely to tell you that part of Roman history.

According to Brinkmann, the downfall of the Roman Republic came from the inability to provide its military veterans enough free land for retirements. An accompany cause of decline was the Roman bureaucracies becoming “masters of the state” instead of its servants.

California’s public pension systems and self-serving bureaucracies are just a modern example of what brought decline to the Roman Empire. Brown sees bureaucracies as un-reformable. The California Energy Commission and the new Department of Business Oversight — renamed the Business and Consumer Services Agency — are both bureaucratic creations of Brown.

Brown: “I can remember the day. August 14, 1956. That’s when I entered Sacred Heart Novitiate. It’s primarily a life of silence, meditation, prayer, and study, with some servile labor mixed in. When I got there, I had my first experience with what was called magnum silencium. The great silence.”

Brown fashions himself as a modern version of an ancient Greek or Roman philosopher-king, but inspired by Zen Buddhism and monastic Catholicism. Like many ancient rulers, he wants to be considered semi-divine.

The Koan is an ancient Chinese practice used to provoke “great doubt” and test a student’s progress in Zen Buddhism. One method is to ask the question: “Two hands clap and there is a sound. What is the sound of one hand clapping?” Answer: It is Jerry Brown congratulating himself for his lack of accomplishment while furthering the eventual ruination of the state. But the sound of one hand clapping is silent. And Jerry Brown loves silence because otherwise he would have to file an environmental noise impact statement for all his self-aggrandizement.

Related Articles

'Consumer' Group Reaps Big Salaries

JUNE 10, 2011 Last week, the Assembly passed AB 52, which would require health insurance companies to seek permission from

Air Resources Board corp facing open meetings

May 30, 2013 By Katy Grimes Stop the presses! A really good Republican bill just passed the Assembly 63-0. What?

Kamala Harris not likely to be Supreme Court nominee

While Kamala Harris has a good shot at becoming the next U.S. senator from California, she has little shot of