Grizzly Bear Project seeks property tax increases

There could be a property tax increase in your future — if the Grizzly Bear Project gets its way. Project head Anthony York is a veteran reporter who has “covered California politics for close to 20 years. Before launching the Grizzly Bear Project in 2015, he covered Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration for the Los Angeles Times.”

There could be a property tax increase in your future — if the Grizzly Bear Project gets its way. Project head Anthony York is a veteran reporter who has “covered California politics for close to 20 years. Before launching the Grizzly Bear Project in 2015, he covered Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration for the Los Angeles Times.”

His survey title asks and answers a question: “Want budget stability? Property taxes may be the answer.” He writes:

Since the early 1990s, we’ve lived through the boom and bust cycles of the California budget. Today, we are more dependent than ever on personal income taxes. And those taxes are more progressive than they have been in years, meaning our economic stability is tied to the fate of the wealthy .

The top 1% pays more than 50% of our income taxes. And income taxes account for two-thirds of the state budget.

There’s been some suggestion from Sen. Robert Hertzberg and others that expanding the sales tax would stabilize our tax base. That approach was rejected when it was recommended by the Parsky Commission in 2009, but Hertzberg wants to have the conversation again.

Another possibility is moving toward a system that is more property-tax based.

He notes that, according to data from the Legislative Analyst, property-tax revenue is a lot more stable than income-tax and capital-gains-tax revenues. During good times, income and cap gains rise quickly, filling state coffers. But during recessions, they drop sharply, causing the infamous budget deficits, which ran to $20 billion during the last years of Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s administration, 2010 and 2011.

The deficits then bring tax increases, largely on income. In 2009, Schwarzenegger increased taxes a record $13 billion. That lasted two years. But Gov. Jerry Brown then pushed through the $7 billion tax increase of Proposition 30 in 2012.

York notes:

Since 1978, the state’s property tax revenues have fallen below the previous year’s totals only twice – with 1% drops each in 2009-10 and 2010-11, as the state coped with the housing crash.In all, there’s been an average of 5% annual growth in property tax revenues over the last 20 years, with the largest single year increases coming in 2005-2007, during the state’s housing boom. (To learn all you ever wanted to know about the state’s property tax, check this primer from the LAO).

Politics

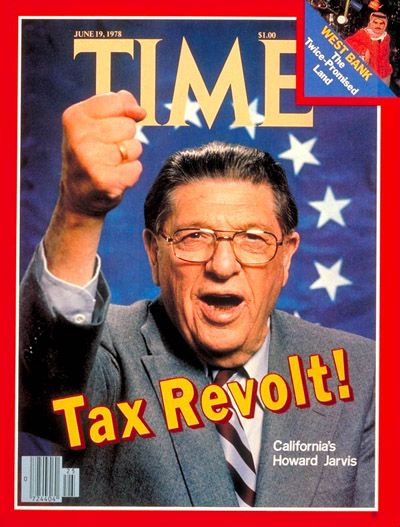

Of course, aside from whether this is a fiscally sound idea, the politics is that Proposition 13 would have to be repealed, or severely modified. The 1978 tax limitation measure remains part of the warp and woof of California politics even as the state’s voters have become more liberal.

The Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, named after the firebrand who sparked the initiative, remains dedicated to defending Prop. 13. So far, and likely for the foreseeable future, it has thwarted any attempts at changing it significantly.

York concedes:

Of course, considering such a system means changing Proposition 13 and Proposition 98, a virtual political hornet’s nest. But part of the idea of this project is to get past the knee-jerk emotional political reactions in hopes of having an honest discussion about whether these ideas are good for the state. If there is strong leadership and a sustained effort to educate, voters can be convinced to go along. The campaign for Proposition 30 proved that.

Except Prop. 30 was sold as taxing rich people to fund schools — and was temporary for seven years (unless it ends up being extended).

Changing Prop. 13 along any significant lines would bring back the horror stories of grandmas turned out of their homes by the grim reaper known as the property-tax assessor.

Gann Limit

Actually, there was a better way to even out spending and taxing: The Gann Limit, which was enacted in 1979, with the support of Gov. Jerry Brown, as a companion measure to Prop. 13.

It limited increases in spending to the increases in population plus inflation. It worked great in the 1980s, until it was repealed by misguided voters in 1990 with Proposition 111. York himself pegs 1990 as the year things went haywire.

The Gann Limit even produced a rebate to taxpayers in 1987. The mechanism was faulty: an expensive mailing of checks to taxpayers. A better idea would have been to just cut taxes for the next year.

Finally, there is another tax reform that would end the volatility problem: A flat tax of about 5.5 percent of income, with no deductions. Brown actually supported a national flat tax when he ran for president in 1992.

Are those reforms — bringing back Gann or a flat tax — just as unrealistic as gutting Prop. 13? Alas and alack, probably.

John Seiler

John Seiler has been writing about California for 25 years. That includes 22 years as an editorial writer for the Orange County Register and two years for CalWatchDog.com, where he is managing editor. He attended the University of Michigan and graduated from Hillsdale College. He was a Russian linguist in U.S. Army military intelligence from 1978 to 1982. He was an editor and writer for Phillips Publishing Company from 1983 to 1986. He has written for Policy Review, Chronicles, LewRockwell.com, Flash Report and numerous other publications. His email: [email protected]

Related Articles

$50 Million-A-Day Budget Talks

Katy Grimes: Sen. Bob Dutton showed an appropriate level of impatience with the continuing spending bills in the Budget Conference

NBC discovers Obamacare is bad for biz

CalWatchdog has done more than 50 stories about Obamacare and the Affordable Care Act since just Januray 1, 2013, warning about the detrimental impacts

L.A. mayor’s State of City address skips economic woes

In January 2014, a blue-ribbon commission created at the behest of Los Angeles City Council President Herb Wesson presented the