Taxation Without Representation?

by CalWatchdog Staff | September 22, 2010 3:23 pm

[1]

[1]

SEPT. 22, 2010

By ANTHONY PIGNATARO

If you’re a politician, pundit or just political junkie, chances are redistricting is on your mind. There are two measures on this year’s ballot dealing with redistricting – Proposition 20[2], which would create a citizens’ commission to draw new congressional districts, and Prop 27[3], which would kill the citizens’ commission created by Prop. 11 in 2008 to draw assembly and senate districts.

That panel – the historic California Redistricting Commission[4] – is still being formed. On Sept. 22 the Applicant Review Panel began meeting in a fourth floor suite on the Capitol Mall to whittle 120 prospective commissioners down to 60. Next year, when the list is down to just 14 members, that panel – and not the partisan Legislature – will take up the delicate task of drawing district boundaries.

And when they do, they’ll run into a little-known, curious phenomenon. “We’re going to have a very strange situation where for two years some people won’t have a senator,” one Democratic staffer told me. “And then there will be some people who will have two senators. I have no idea how they will work that out.”

Those who wind up without a senator are called “deferred voters.” Those with two are known as “accelerated voters.” They are unavoidable consequences of redistricting senate districts (assembly districts are immune, for reasons explained below) and they pop up all over the state regardless of who draws the new boundaries. There’s also no way to predict, until the maps are drawn, who will become one.

To say the study of deferred and accelerated voters is obscure is an understatement; in fact, many academics and officials who delve into redistricting on a regular basis have either vague or no knowledge of them.

“Oh, that does happen,” Bob Stern, president of the Center for Governmental Studies[5] in Los Angeles, said of deferred voters. “My guess is the senator who used to represent the area will continue to handle constituent services, but that’s just my guess.”

Margarita Fernandez, an official with the state auditor’s office who is handling media affairs for the new California Redistricting Commission, said she’d never heard of the phenomenon when called for comment.

“It’s an unavoidable byproduct of having staggered Senate seats,” Darren Chesin, the chief consultant to the Senate Committee on Elections, Reapportionment and Constitutional Amendments[6], said. “And you can’t prohibit it, unless you get away with staggered Senate elections.”

Put very simply, voters get “deferred” when their district, or just a portion of their district that they happen to live in, gets folded into a new district with a later election date than they were used to. Instead of voting for a new senator right after redistricting, they end up having to wait in a senator-less frontier for the following election.

“If you’re living in an odd-numbered district now, and redistricting puts you in an even-numbered district, then you could be deferred,” Chesin said. “And now, congratulations. You’re now the third person in the state who understands this. Now you can bore people at cocktail parties.”

Accelerated voters occurs when a voter’s new district election coincides with the old one, meaning that two senators will, until the election after redistricting, hold jurisdiction over the same territory. But this is less ominous than deferring voters (or, in truth, residents) since senate representation for all is required by the state constitution.

“The Senate Rules Committee[7] always ends up essentially appointing a senator for any area that is deferred,” Chesin said. “In a way, it has to be this way because you never know where the lines will end up.”

No one contacted for this story could come up with an estimate of how many people may end up deferred or accelerated when the Redistricting Commission finishes its work next year. “There’s no way to tell,” Chesin said. “You don’t know which given area would move from odd to even.”

Scott Sullivan of the Senate Office of Demographics[8] agreed. “It’s not knowable,” he said. “It just depends on how boundaries cross.”

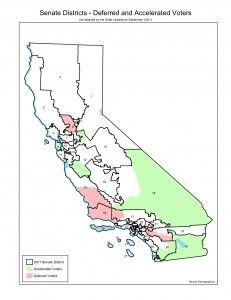

That may be true, but Sullivan was able to provide surprisingly precise figures as to how many people were deferred or accelerated following redistricting 10 years ago. According to Sullivan, a decade ago California wound up with 2,983,372 accelerated residents and 3,424,984 deferred residents (see map below).

[9]

[9]

That’s more than 5 million people. One of them, Tedda Oldknow, who today also works out of the Senate Demographics Office, found out about her status the hard way.

“I was a deferred voter,” she said. “I lived in the 5th District, and we got to use our old district.” Oldknow said her old senator provided any constituent services that were needed.

But Oldknow also discovered something disconcerting about being a deferred voter. Because of the sheer numbers of people involved, no notices were sent out telling people of their new “deferred” status. She found out entirely by accident when she called her old senator, only to be told that he wasn’t technically her senator anymore.

It’s a problem that organizations like the League of Women Voters[10] know very well when they try to conduct grass roots campaigns.

“It comes up in our organization when we talk about people contacting their legislators,” Trudy Schafer, the Senior Director for Program for the League’s California office, said. “It’s just this awkward thing. It’s a time when people may need assistance.”

Photos: California State Senate courtesy Wiki Commons; map generated by Senate Demographics Office.

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/800px-California_Senate_chamber_p1080899.jpg

- Proposition 20: http://ballotpedia.org/wiki/index.php/California_Proposition_20,_Congressional_Redistricting_(2010)

- Prop 27: http://ballotpedia.org/wiki/index.php/California_Proposition_27,_Elimination_of_Citizen_Redistricting_Commission_(2010)

- California Redistricting Commission: http://www.wedrawthelines.ca.gov/

- Center for Governmental Studies: http://cgs.org/

- Senate Committee on Elections, Reapportionment and Constitutional Amendments: http://www.sen.ca.gov/ftp/sen/COMMITTEE/STANDING/EL/_home1/profile.htm

- Senate Rules Committee: http://www.sen.ca.gov/ftp/sen/committee/STANDING/RULES/_home1/PROFILE.HTM

- Senate Office of Demographics: http://www.sen.ca.gov/ftp/sen/offices/demographics/_HOME/

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/here.jpg

- League of Women Voters: http://ca.lwv.org/

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2010/09/22/taxation-without-representation/