SFSU Whitewashes History

by CalWatchdog Staff | January 20, 2011 1:59 pm

[1]JAN. 20, 2011

[1]JAN. 20, 2011

By STAN BRIN

My alma mater, San Francisco State University, celebrates Nov. 6, 1967 as the birth of a movement to create the first department and college of Ethnic Studies[2].

I remember Nov. 6, 1967 very differently, as a bad day, a violent day. It was bad for the students, bad for California, and bad for the integrity of scholarship. Myths surrounding that day, and subsequent events tied to it, allows the university to push an entirely fabricated history of itself, and a nasty and dangerous agenda.

Every year, the university’s College of Ethnic Studies sends me a series of emails, each kindly inviting me to a weekend of festivities surrounding this day. This year’s events featured the unveiling of a plaque honoring the campus Black Students Union, the third such tribute that the BSU has received in three years.

The College of Ethnic Studies served “sumptuous hors d’oeurves” (sic) and had a great time at a Persian restaurant.

I didn’t go. I knew the Black Students Union. It was a gang of goons.

And Nov. 6, 1967 was an especially bad day for me – I could have been killed.

The Fire At Merced Hall

I was a sophomore back then, just turned 19 years old when, on the morning of Nov. 6, 1967, I awoke in my fifth-floor room to a screaming fire alarm. I figured it had to be a prank. But residents on the other side of the hallway saw smoke and flames rising below their windows. So we put on our slippers and bathrobes, and raced down the fire escapes. On the ground, we found smoke and fire spewing from the windows of the dormitory lounge, a one-story add-on that faced the street. By then flames rose 20 or 30 feet above the roof.

The logbook of the San Francisco Fire Department states that three fire companies appeared at Merced Hall at 6:17, 6:24, and 6:27 a.m. The fire left the lounge a blackened, roofless, windowless wreck, but there were no injuries. Rooms on the first floor suffered smoke damage, but the main structure of Merced Hall stood unscathed. The quick response of firefighters and the building’s concrete construction prevented the fire from spreading, but had the fire escapes been blocked, hundreds would have suffocated.

An hour or so later, the firefighters left. We were allowed into our rooms and went to class.

While there was no physical evidence pointing to anyone, other evidence suggests that more than one individual was involved. The doors of Merced Hall were locked from inside at 10 p.m., indicating that someone inside the building had to open a locked door and allow entry to at least one accomplice to carry in the accelerant used in the fire.

The fire at Merced Hall was front-page news in the San Francisco press for two days, and there were at least 800 witnesses, 405 in Merced Hall, and 400 more in the directly adjacent women’s dorm, Mary Ward Hall. The university’s president John Summerskill labeled the fire “arson,” but the event was quickly forgotten. No one ever claimed credit, no arrests were made, and today neither the fire department nor the police department can confirm that an arson investigation ever took place.

Oddly, the university now maintains that the fire never happened. Its official Web site[3] specifically ignores it. If former students ask about the fire, university officials tend to react with silence, anger and lies, even screaming.

“There was no fire at Merced Hall!” a librarian shouted at alum Mark Seidenberg, a former high ranking official of the Department of Transportation in Washington.

“What do you mean it never happened?” an astounded Seidenberg replied. “I was there!”

And the bad day at SF State had just begun.

The Black Students Union

To appreciate what happened next, it is important to understand what the Black Students Union[4] was, and who its members were.

By 1966, the methods and ideas of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bayard Rustin that led to the landmark Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 were out of fashion on university campuses. The new ideology, Black Power, was an odd mélange of racial separatism, pan-African nationalism, pseudo-Marxism and fascism.

Formed in 1966 out of the former Negro Students Association, the BSU adopted Black Power ideas and a style that can only be described as Nazi-inspired. They wore black uniforms and berets, they goose-stepped across campus, they converted the black-power fist into a stiff-arm salute. They held Wagnerian rallies that appeared to have been adapted from close study of Triumph of the Will. Members felt the need to literally growl when white students stood too close.

A wall poster popular with the BSU portrayed a black man standing on a tiny rock in the middle of a storm-tossed sea. He carried a spear and wore a leopard-skin loin cloth, a Mephistophelian pointed goatee, and an expression of inchoate rage, his fist shaking at an unseen, all-powerful enemy. Paranoia, narcissism, anger and hatred.

The BSU formed an alliance with the campus white radical power structure, an odd mix of red-diaper types who used compulsory student government fees as a piggy bank. The BSU became the radicals’ strong-arm gang, used to snarl at opposition candidates and intimidate voters, a sort of Bay Area Sturmabteilung.

Members of the student legislature who resisted BSU demands were threatened. In one famous case, they resisted orders to cancel concerts by famed saxophonist John Handy and hand the funds to racist playwright Leroi Jones and the BSU, no questions asked. The administration and faculty representatives on the legislature supported the BSU, and the student representatives caved in. (As “Amiri Baraka,” Jones became poet laureate of New Jersey in 2001. His racial and anti-Semitic animus forced the state to abolish the post two years later in order to get rid of him.)

The BSU threatened opponents relentlessly, and without apologies. BSU member and Black Panther “Minister of Education” George Murray, told Examiner reporter John Hurst a month later[5], on Dec. 13, 1967:

“Black people cannot commit any crimes against white people. Anything we do to the ‘dog’ cannot be wrong. The only crimes we can commit are crimes against humanity. And white people aren’t part of humanity.”

The BSU’s “on-campus coordinator” Jerry Varnado, told Hurst, that a white man “asked me why they (BSU members) called him a racist dog, and he said it hurt him. I said that shouldn’t hurt him because if somebody came up to me and called me a man, it wouldn’t hurt me – because I am a man.” Varnado is now a retired attorney living in a prosperous suburb, one of many former BSU members who became professionally and financially successful. The College of Ethnic Studies’ honors Varnado as one of its “leader donors.”

Hurst concluded, “With the enemy defined, the anything-goes philosophy is justified by dehumanization.”

And while the BSU has never been linked to the Merced Hall fire, arson was in its blood. According to a report of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence (NCCPV), on Nov. 8, 1968 alone, BSU “raiding parties” set approximately 50 fires in campus buildings.

The Gater Raid

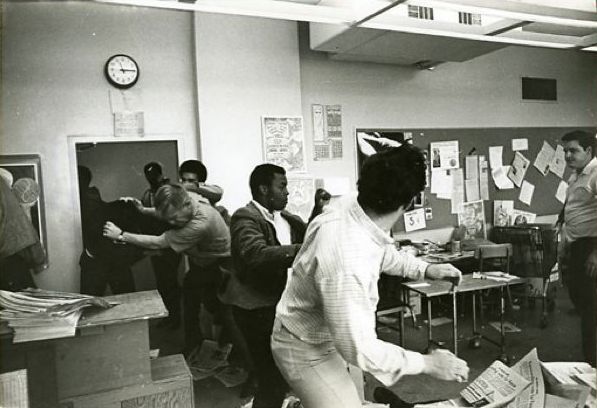

Roughly five hours after the attack on Merced Hall, 10 members of the BSU, some wearing sport coats, some dressed in the group’s black leather uniform, burst into the office of the student newspaper, then called the Golden Gater. They proceeded to beat and kick the staff and faculty advisers. Gater editor Jim Vaszko and Lynn Ludlow[6], a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner and professional adviser to the Gater, were among the injured.

I was introduced to Vaszko by the paper’s previous editor, Ben Fong-Torres, later to gain fame as a co-founder of Rolling Stone. We hung out a few times. Vaszko later became a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner, until he was gunned down on May 1, 1990, while riding his bicycle, a victim of another violent attack.

Ludlow, now retired after a career at both the Examiner and the Chronicle, recalls that BSU member George Murray and several others stood by the door to block the exit while the rest attacked the staff, overturned desks and threw down typewriters.

“They punched and kicked Vaszko in the kidneys until he was spitting blood,” Ludlow recalls. “He was hospitalized for two days.” Ludlow’s finger was broken in the melee, and he never regained full use of it.

Like the fire, the attack on the Gater staff might have disappeared down a memory hole if not for student photographer Bill Owens. He hid beneath a desk and snapped pictures while, as Ludlow, remembers, student secretary Linda Gallagher “picked up a phone to call the campus police.” Or, rather, tried to call the police: Ludlow says a BSU member “tore the phone from the wall.”

The assailants left as suddenly as they came – and ran straight to the office of campus President Summerskill, where they hung about in an effort to establish an alibi. The tactic didn’t work. According to Ludlow, “Bill Owens immediately developed the pictures and hand carried copies to Summerskill’s office, which took care of the denials.”

When it became clear that Gater staffers would press charges, Summerskill himself appears to have arranged legal defense for the BSU, an attorney who would soon become the king of Sacramento, Assemblyman Willie Brown.

Ten members of the BSU surrendered to the police, six of them on Friday, Nov. 10 their names published in the Examiner. Among those surrendering to police and named in the Examiner was “Danny L. Glover, 21, of 860 Oak St.” If the name sounds familiar, it appears to be that of the future film star, Danny Glover, who was, by his own admission, a BSU activist at San Francisco State. In a 2002 article published in the journal “Crossroads,” Black Panther Kathleen Cleaver[7] confirmed that the actor Danny Glover formerly lived on Oak Street. When contacted through his publicist, the actor refused to confirm or deny his participation in the Gater attack.

George Murray was also among those arrested.

The arrestees were charged with assault and conspiracy and quickly released on bail. They never explained why they attacked Vaszko and the others. At times, they claimed that they were angered by Vaszko’s disdain for Muhammad Ali’s membership in the Nation of Islam, at others that they didn’t like the Gater’s long-standing opposition to the BSU’s fund-raising schemes and threats against student leaders.

According to Michael Grieg, writing in the Chronicle on Nov. 7, student president Phil Garlington, later a reporter for several leading California newspapers, claimed that the “triggering” incident was the recent election for homecoming queen. The BSU candidate came in second, causing the group to cry foul.

Two unnamed BSU members were immediately suspended.

The Aftermath

While the BSU perpetrators didn’t like being arrested for the Gater attack[8], they hated being suspended even more. They created a “Movement Against Political Suspensions” and launched a seemingly endless wave of protests, break-ins and general mayhem across campus.

According to the Examiner of Dec. 1, when a Nov. 31 meeting of the student legislature refused to approve a slate of student appointments consisting entirely of BSU members, Jerry Varnado stood and told the body, “we will move outside the law.” He pointed to the members, one by one, and said, “We will move over you… or you… or you…” Varnado added, “Anybody who wants to come up and put me down can try.” Twenty BSU members attending the meeting laughed. Varnado then overturned a table.

Students appealed to President Summerskill to halt the violence, but he refused. “If I interfere in student affairs,” he said, solemnly, “it will mean the end of student self-government.”

“Even to prevent intimidation and ensure fair elections?” he was asked.

He didn’t understand the question.

The spring riots of 1968 eventually caused Summerskill to suddenly fly to Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, in search of another academic gig. Chancellor Glenn Dumke of the State University system caught up with Summerskill by phone at the airport and fired him on the spot. Summerskill’s successor, Robert Smith, lasted nine months.

The radical-controlled Associated Students Board of Publications took over the Gater. The paper became violently radical – and all but unreadable by the students whose compulsory fees paid its bills. Student journalists complained of political censorship and control. In response, the journalism faculty started their own newspaper, appropriately named the Phoenix, which they financed out of matching grants and prize money.

Precisely a year after the Merced Hall fire and the Gater attack, the members of the BSU’s central committee issued a set of 10 “non-negotiable” demands. This decalogue commanded the administration to create a Black Studies department staffed with no fewer than 20 full-time professors of the BSU’s choosing, nearly one professor of Black Studies per 10 or 12 black students. In addition, any non-white who applied to the university was to be admitted, regardless of qualifications.

The BSU ordered all of the university’s 18,000 students to boycott classes, and enforced their ultimatum with threats, beatings and vandalism. They were very persuasive — not for their logic, but for the very absence of any logic but terror.

The ensuing four-month brawl, the most violent and prolonged of the era, is known to historians as the “Student Strike” – but there was no strike vote. No one ever asked the students if they wanted to dodge strangers bent on grabbing their genitals or yanking their nipples as they got off the trolley car. Or if they wanted a trash can thrown through a plate glass door by a grinning mob.

President Smith resigned in November, 1968, and renowned semanticist Professor S.I. Hayakawa volunteered to replace him. Hayakawa quickly gained national fame by pulling out speaker wires from a sound truck, which was, again, paid for with compulsory student fees.

This act may have enraged the radicals, but it didn’t stop them. Like his predecessors, Hayakawa failed to block the radicals’ control of student funds, and the riots rolled on. They took place every school day, from roughly 11 a.m. to 1 p.m., rain or shine, from November, 1968 through the third week of February, 1969.

Taking advantage of the mayhem, the San Francisco State local of the American Federation of Teachers authorized its own “strike.” For some reason, the AFT picketed and shut down the dorm dining hall, forcing 800 students to live on pizza and canned soup, but the AFT professors weren’t actually striking, merely scamming the system. They stayed home, did nothing, and continued to receive paychecks, while their students lost an entire semester.

The “strike” finally ran out of steam in mid-February. Deputy Attorney General Joanne Condas, in charge of prosecuting corruption cases involving non-profits, asked Superior Court Judge Edward F. O’Day to shut down the student government. She did this only after a student whistleblower threatened to sue her for inaction. Condas and her colleagues had sat on piles of incriminating evidence for six months, since the previous August.

On Feb. 17, Judge O’Day agreed with Condas. He concluded that the law did not permit the BSU and other radicals to stage phony elections, loot student funds, or assign each other federal work-study grants. Judge O’Day placed the student corporation in receivership, freezing the radicals’ money. They had to find jobs. The daily riots ended overnight.

The BSU’s attacks against students finally ended with an abortive bombing of the Creative Arts building on March 5, 1969, in which the bomber injured only himself. (Such was the administration’s “understanding” of the BSU that, following his recovery, the bomber was allowed to return to class.) Oddly, for all their violence and bluster, the BSU never actually killed anyone.

By then, an estimated 4,000 students had transferred to other campuses.

President Hayakawa became a hero. He appeared on the Johnny Carson show, and in 1976, the public rewarded him with a six-year term in the U.S. Senate. Sadly, Hayakawa’s habit of sleeping through debates and committee hearings soon made him a national joke. He didn’t bother to run again.

Legacy

These days, the university’s College of Ethnic Studies regards the BSU’s non-negotiable demands, as well as five similar demands from the “Third World Liberation Front,” as its founding charter, something like the Declaration of Independence.

Actually, according to books written by two former presidents and another by the NCCPV report, the administration was already formulating plans for black and ethnic studies programs and raising funds for them. In fact, the strike ended without any of the BSU’s demands having been met. They could not have been met – many required strict racial tests for admission and hiring, which violated state and federal law. Others required money that would have required a special appropriation by the state Legislature and approval by then Gov. Ronald Reagan, which were unlikely events.

All of this seems forgotten in the rush to celebrate the unquestionable gains of African Americans, the most salient of which was the election of Barack Obama to the White House.

But recognizing the ways in which America is a better place has, at least on the campus of SF State, become an opportunity to mythologize the excesses of a group of thugs and maintain a climate of pseudo-scholarship.

Today, SF State remains a uniquely unfriendly place for those with views at odds with the school’s ideologically motivated faculty and administration.

And the fire at Merced Hall never happened.

Stan Brin is a journalist specializing in business and politics living in Aliso Viejo. He is a graduate of the American Film Institute, a former software entrepreneur, and is currently working on a novel about the years preceding the First World War.

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/gaterattack.jpg

- San Francisco State University, celebrates Nov. 6, 1967 as the birth of a movement to create the first department and college of Ethnic Studies: http://www.sfsu.edu/~ethnicst/41hosts.html

- official Web site: http://www.library.sfsu.edu/about/collections/strike/chronology.html

- Black Students Union: http://articles.sfgate.com/2010-02-01/news/17841847_1_black-studies-black-student-unions-bet

- BSU member and Black Panther “Minister of Education” George Murray, told Examiner reporter John Hurst a month later: http://ec2-174-129-179-30.compute-1.amazonaws.com/articles/archives/1968/apr/11/trouble-at-san-francisco-state-an-exchange/?pagination=false

- Lynn Ludlow: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/e/a/1998/03/01/SPECIAL804.dtl

- In a 2002 article published in the journal “Crossroads,” Black Panther Kathleen Cleaver: http://www.prairiefire.org/CRSN/CRvol10no31.pdf

- Gater attack: http://books.google.com/books?id=DKKhz_XVrDcC&pg=PA47&lpg=PA47&dq=Jerry+Varnado+gater+attack&source=bl&ots=8Tk-2zvPvY&sig=ShHM1gsXTPBrO2VjSZu39QlEzhU&hl=en&ei=F5E3TfyqN4e4sAPQ3L2wAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Jerry%20Varnado%20gater%20attack&f=false

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2011/01/20/sfsu-whitewashes-history/