Pensions May Be 'Touchable'

by CalWatchdog Staff | February 11, 2011 3:44 pm

[1]

[1]

FEB. 11, 2011

By TROY ANDERSON

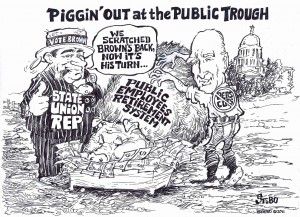

The prevailing wisdom holds that existing public pensions – once converted into Cadillac plans – can’t be turned back into Oldsmobiles.

For decades, union officials have repeated the mantra that government agencies can’t modify or reduce pension benefits without violating the constitutional prohibition against impairment of contracts.

But a growing number of legal experts say public agencies may have far more latitude to change retirement benefits – especially future benefits earned by current employees – than once commonly believed.

“We’ve looked at the case law very carefully and our view is very different than the so-called talking heads – be they politicians, union leaders or whatever,” says Jeff Chang, an attorney at Chang, Ruthenberg & Long, a Folsom-based firm that is advising government agencies throughout the state about their legal options to reduce pension costs. “The case law is much more ambiguous and refined. It’s not nearly as black and white.”

CalPERS spokesman Ed Fong disagrees.

“Litigation in this area has never supported this view,” Fong says. “Courts have always ruled that vested retirement benefits cannot be taken away or reduced once they are earned.”

As public pension costs consume 25 percent to 50 percent of the payrolls of a growing number of agencies throughout the state and nation – raising concerns about tax increases, reduced public services and a wave of municipal bankruptcies – officials are asking the once-taboo question of whether it may be necessary to seek to reduce promised pension benefits.

“It’s a very hot topic,” says Lisa Hill Fenning, a Los Angeles attorney and former U.S. bankruptcy court judge who will speak about the controversy Feb. 17 in Irvine during a California Foundation for Fiscal Responsibility[2]-sponsored boot camp for elected officials. “Ultimately, the question that is going to be posed in the courts is whether the modification of these pensions is necessary to save everybody.

“If a government agency is otherwise going to run out of money – won’t be able to pay its pension obligations, can’t pay its current employees and can’t provide basic services – then everybody might agree it’s necessary. Most likely it will be debated in the political arena. These types of discussions have already been going on in academia and the bar.”

These discussions come as state lawmakers have bestowed generous pension increases upon public servants in recent decades. As a result, taxpayers are now on the hook for trillions of dollars. In California, the average state retirement packages now valued at more than $1.2 million, according to the CFFR.

Joe Nation, a professor of the practice of public policy at Stanford University, says the estimates of the unfunded pension liabilities in California alone range from $265 billion to $737 billion[3].

“I think most jurisdictions and pension systems are beginning to understand that unless they have the authority to modify benefits going forward for current employees that there is really no way to dig out of the hole they are in,” Nation says. “I think a lot of cities are going to find they simply can’t afford to continue to pay these pensions unless they get rid of a majority of the services they provide. The question is can jurisdictions ask voters for tax increases. I think that is going to be a tough sell, especially to fix a system that most people think is broken.”

Throughout the nation, experts are warning of the approaching insolvency of state and local retirement plans. Experts at the University of Chicago and Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management estimate public pension funds nationwide are unfunded to the tune of more than $3.2 trillion.

Currently, 7 million public retirees are collecting pensions from government retirement plans. An additional 20 million Americans have been promised these benefits. But by 2020, 10 states are expected to exhaust their pension funding. All but eight of the 50 states are expected to run out of pension money by 2030, including California in 2026, according to U.S. Rep. Devin Nunes, R-Tulare, co-author of the Public Employee Pension Transparency Act[4].

The act provides enhanced transparency for state and local pensions and also establishes a federal prohibition on any future public pension bailouts by the federal government.

“You can’t get around these numbers,” says Nunes’ communications director Andrew House. “The period when you could put your head in the sand and put this off – that period is ending for most of the states.”

In response, officials throughout California are quietly discussing the legal options they might have to address the soaring costs.

Manteca City Manager Steve Pinkerton raised the issue in a recent blog post entitled – “Are Government Pensions Untouchable?”[5]

“I’m beginning to see a groundswell of discussion from legal experts who claim that government pensions aren’t as untouchable as labor would like us to believe,” Pinkerton wrote. “One California law firm in particular has been making some fairly bold statements about the ability to challenge public employee pensions.”

In a position paper on its Web site, the law firm of Chang, Ruthenberg & Long cited one of the leading cases in pension law – Kern v. Long Beach[6]. The case involved a retired firefighter who sued Long Beach in 1945, alleging the city rejected his application for retirement benefits on the grounds the benefits had been eliminated by charter amendment 32 days before he completed 20 years of service. The state Supreme Court heard the case in 1947 to determine if he had a vested right to a pension that the city could not abrogate by repealing the charter provisions without impairing its contractual obligations. The high court found pensions for public employees are more than a “mere gratuity” and a “pension right … cannot be destroyed, once it has vested, without impairing a contractual obligation.” However, the court also found that while an employee “may acquire a vested contractual right to a pension” the government is allowed to make modifications and changes in the system.

“The employee does not have a right to any fixed or definite benefits, but only to a substantial or reasonable pension,” the justices wrote.

Taken as a whole, Chang says the case does not mean that pension benefits can’t be modified or reduced. Although public employees have a right to participate in public pension programs, government agencies have the right to modify or change the system – particularly if the changes are necessary to address a budget crisis, Chang argues.

Under federal anti-cutback rules, Chang says if a government agency is going to reduce a pension benefit it at least has to preserve the amount of the pension the employee has already earned.

“If you believe that is what the case law intended, then the extension of that means you should be able to change things they have not yet earned,” Chang says. “I believe the courts in their wisdom never intended to say anything more than you cannot cut back an already earned and vested benefit, but I don’t think they ever intended to say you can’t change the formula.”

This particular aspect of the case law is drawing attention because one of the most critical pieces of legislation that expanded public pensions was SB400, a bill state lawmakers approved in 1999 that raised benefits as much as 50 percent for some employees. The adoption of SB400 ushered in an era of dramatic pension increases, including the “3 percent at 50” formula that allowed California Highway Patrol officers and other public safety officials with 30 years of service to retire with 90 percent of their final salary as young as 50 years old. The bill sparked a wave of public employee pension increases in cities, counties and other government agencies throughout the state and caused an exodus of public employees into the ranks of retirees.

Amy Monahan, an associate professor of law at the University of Minnesota, says a degree of uncertainty exists in terms of how courts might view prospective pension changes such as altering the “3 percent at 50” and similar formulas with respect to future service in order to reduce pension costs.

But even if the courts ruled state lawmakers couldn’t change pension formulas affecting workers’ future benefit accruals, Monahan says states could ultimately use their “police powers” to reduce pension costs.

“It’s possible that the state’s fiscal situation is bad enough that it would justify a change to an otherwise enforceable contract about future benefit accruals and that it would make changes permissible, essentially because the changes would be considered necessary to protect the welfare of the state and its citizens,” Monahan says.

Already, lawsuits have been filed against three states – Minnesota, Colorado and South Dakota, after state lawmakers rolled back cost-of-living increases for retirees, Monahan says. None of the lawsuits have been resolved yet.

“These are the people who have already performed their service, accrued their pensions and they are changing them post-retirement,” Monahan says. “That is, in my opinion, the legally riskiest thing to do. In terms of what is less risky – new hires are easy. You can do whatever you want with new hires. But with respect to people already in the system, changing benefit accruals going forward should be the least risky option.”

Alexander Rubalcava, president of Rubalcava Capital Management, an investment advisory firm in Los Angeles, says the long-held assumption that existing pensions can’t be modified has served to prevent any challenges until recently.

But he expects government agencies to take bolder steps in the years ahead as many are left with no choice.

Rubalcava, along with former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan, have warned for years that Los Angeles will likely face bankruptcy by 2014 as annual pension and retiree health care costs increase by $2.5 billion, consuming an ever-larger share of the city’s budget.

“It’s a real question as to how this will all play out,” Rubalcava says. “It reminds me of a chess board where two moves have been made in the game. We are two moves into the game now and it’s very hard to know where it all goes from here.”

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/Stebo_edited-34.jpg

- California Foundation for Fiscal Responsibility: http://www.californiapensionreform.com/

- Joe Nation, a professor of the practice of public policy at Stanford University, says the estimates of the unfunded pension liabilities in California alone range from $265 billion to $737 billion: http://publicpolicy.stanford.edu/node/3985

- U.S. Rep. Devin Nunes, R-Tulare, co-author of the Public Employee Pension Transparency Act: http://nunes.house.gov/

- Manteca City Manager Steve Pinkerton raised the issue in a recent blog post entitled – “Are Government Pensions Untouchable?”: http://blog.mantecagov.com/2011/01/are-government-pensions-untouchable.html

- Kern v. Long Beach: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=13843607586715098523&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2011/02/11/pensions-may-be-touchable/