Little Hoover Critiques Community Colleges

by CalWatchdog Staff | June 27, 2011 9:38 pm

[1]JUNE 28, 2011

[1]JUNE 28, 2011

By DAVE ROBERTS

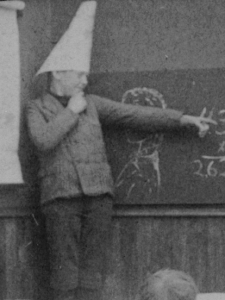

If California’s educational system were a student, it would be made to sit on a stool in the corner with a dunce cap on its head.

Nearly one in four Californians is functionally illiterate, about a third of high school students drop out and 70-80 percent of the high school graduates who go on to college require remedial classes in English and math. More than 4.6 million Californians age 25 or older lack a high school degree, ranking the state 48th in the country.

With the K-12 system having dropped the ball, the burden has been placed on the state’s community colleges and adult education programs to provide the knowledge and job skills for those wanting to do more in life than flip burgers or commit crimes.

Unfortunately, as the independent state oversight agency the Little Hoover Commission learned last week, there’s a lack of funding, duplication of resources and confusion over how to meet that need. And with the impending retirement of the Baby Boomers, the need for skilled, educated workers will grow dramatically in the coming years.

“In 2008 the head of the U.S. Department of Education said California has the best adult education system in the country by far,” Patrick Ainsworth, assistant superintendent for the California Department of Education, which oversees adult education, told the commission. “Things were going on that are not in any other state. They wanted to use us as a model. But since then a large portion of our adult education system has been dismantled. We have a shell of what our fomer programs were.”

In the 2008-09 school year, more than 1.2 million Californians were enrolled in adult ed courses, a figure which has been cut in half due to school districts hit by budget cuts transferring funding to K-12 classrooms. The state has more than 350 adult ed schools operating out of more than 1,000 sites such as neighborhood schools and community centers.

The state’s 112 colleges serving 2.7 million students have also had to scale back due to decreased funding. In 2009-10 the colleges were hit by $520 million in cuts, equaling 8 percent of the budget and resulting in 140,000 students being turned away, according to California Community Colleges Chancellor Jack Scott. An additional $290 million in reductions proposed for 2011-12 would result in another 140,000 students losing access due to further course reductions and the elimination of some career training programs.

Functionally Illiterate

“The National Center for Education Statistics says 23 percent of our adult population is functionally illiterate, unable to fill out a job application and manage their affairs,” said Ainsworth. “Pressure from unemployment is driving many people to get retrained. Between the two of us (community colleges and adult ed) we are faced with this gigantic problem of a huge underclass in our state who previously had the commitment to provide a second chance.

“We have equality of opportunity in our country — now that is in question. Do we have that safety net in place? It’s been eroded. Now we are in even worse shape. School districts, one-third of funding has disappeared over the past three years. They are going to make children their first priority [over adult ed]. From an economic development point of view we have to confront this issue. Are we or are we not going to provide a system that gives people a leg up and provides for their futures?”

There were no answers to that question at the 4½-hour commission hearing, but it doesn’t look good.

The problem starts, of course, with K-12 education, which allows students to graduate high school after taking an exit exam that certifies that they can read at a 10th grade level and do math at an 8th grade level. As a result, many graduates are two or more grade levels below what they need when they get to college.

“When someone has graduated from high school and shows up with below two levels of proficiency and you’re telling them they are not college-ready, is that the first time they are hearing it?” Commissioner Victoria Bradshaw asked Constance Carroll, chancellor of the San Diego Community College District.

“Yes, they have been told otherwise throughout their secondary experience,” replied Carroll. “We need to do something about the level of proficiency that high school students achieve. When there’s a gap between 10th-grade proficiency and grade 13 where colleges start, we should put a great deal of effort in bringing those proficienies up to the college level. Almost all of the new jobs require at least a year of post-secondary education. That starts at grade 13, not grade 11. Getting people ready for college and for jobs should be one and the same goal.”

Model Program

The San Diego Community College District is actually a model of what should be happening in post-secondary education. It’s one of the few areas in the state that integrates its colleges and adult education programs. In much of the state, community colleges and adult ed are separate fiefdoms dealing with similar students and with the similar goal of educating and training those seeking a GED or needing to learn English as a second language or gain job skills.

“I worry that California as a state doesn’t have the same integrated approach,” said Carroll. “We have an emergency we are dealing with in remedial problems. Students are not college ready. From my viewpoint after 33 years in California community colleges we have bifurcated systems that are not really integrated with each other, as many of us think they should be.”

As a result, many students are not sure whether they are better off in an adult ed school or community college, finding similar offerings in both. The “one-stop shop” in the San Diego District helps guide them in the right direction, but elsewhere they may be on their own.

Too Many Goals

Another problem is that adult ed programs have been all over the map trying to be all things to all people, which is a luxury that may be no longer affordable in tight budgetary times and with unemployment at 11.7 percent in the state.

“Districts have expanded their services, going into retirement homes, they have gotten so far from their core mission,” said Commissioner Marilyn Brewer. “Classes on wine tasting and how to design t-shirts. They are using state resources to provide those classes when they could be doing basic education and things that could promote emploment.”

Commissioner Eugene Mitchell agreed, saying, “That’s the concern I have. When 90 percent of students aren’t prepared for college you would think for the benefit of the State of California how we would use the capacity for that population. The economic crisis that has beset this country dictates we move in a different direction. People just want to get a job. I don’t have as much heartache over [course] reduction in other directions.”

The commissioners are also concerned that the measurement of success of the programs is inadequate other than just moving students through the system, and that there is not a standardized system of coursework and testing.

Good Job

California Community Colleges Vice Chancellor of Academic Affairs Barry Russell told them, “We are doing a good job of getting more students to completion of these courses. We are moving them to the next level, getting them out of basic skills and into job training at a higher rate than we have had in the past. We are not sure we can measure how much better is this student than the last time.”

Commissioner David Schwarz asked, “Don’t you want to know how your community colleges are doing? Providing the same test? It may be a wake up call or greatly reassuring. At the end of the day you don’t know, other than passing people through, whether their proficiency is increasing. That’s troubling to me. You may be finding they are not doing as well as their counterparts in the Department of Education. You should know that.”

The California Budget Project recently issued a report, “Gateway to a Better Future: Creating a Basic Skills System for California[2],” which concludes, “T]here is serious need for reform. Discussions are underway in the California Department of Education and the California Community Colleges about how to improve basic skills instruction in both systems and coordinate them more effectively. To date, however, the task of reforming basic skills education has not been addressed with sufficient urgency. The conclusions reached by many experts in the past have been largely ignored. Now there is growing clarity based on research, the experience of other states, and innovative California programs about what works and what does not. The critical next step is to overcome institutional and policy inertia and translate these lessons into practice.”

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Dunce_cap_from_LOC_3c04163u.png

- Gateway to a Better Future: Creating a Basic Skills System for California: http://www.cbp.org/pdfs/2011/110506_Basic_Skills_Gateway.pdf

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2011/06/27/little-hoover-critiques-community-colleges/