Water Wars Flood L.A. Central Basin

by CalWatchdog Staff | January 29, 2012 10:34 pm

[1]JAN. 30, 2012

[1]JAN. 30, 2012

By WAYNE LUSVARDI

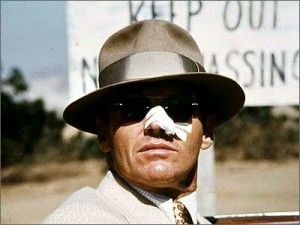

Remember “Chinatown[2],” the murky 1974 movie about the water wars in the Los Angeles Basin in the 1930s, starring Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway?

A January 18 California appeals court water rights case is reminiscent of the multilayered plots and subplots in the flick.

The “Chinatown” movie plot involves fictional character Hollis Mulwray who is murdered due to his opposition to the proposed construction of a new dam. The fictional Mulwray is based on the real historical person of William Mulholland, the infamous head of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, who allegedly stole water from Mono Lake in Northern California in the early 20th Century.

But the current court case is not like the movie “Chinatown” in one important aspect. There is no sex involved in the putting in and taking out of water from the Los Angeles Central Basin Water District water basin that is the focus of this court case. But there is alleged bureaucratic bigamy and robbery.

Quoted in the Long Beach Press Telegram newspaper, Long Beach City Water Department Director Kevin Wattier[3] succinctly summed up the main issue in the case, “Right now it’s like a bank account where you can put money in but can’t take it out.”

The legal citation for the current case is Water Replenishment District of Southern California versus the City of Cerritos[4], Case No. B226743, Second District Court of Appeals, filed Jan. 18, 2012.

[5]The Plaintiffs

[5]The Plaintiffs

The original complainants (plaintiffs) were five cities and a regional water replenishment district: Long Beach, Lakewood, Los Angeles, Huntington Park and Vernon; and the Water Replenishment District of Southern California.

A water replenishment district is a special agency of government that recharges underground water supplies from natural rainwater runoff captured from a local watershed. In this case the water recharge basins are adjacent to the upper San Gabriel River and the 605 Freeway in Los Angeles County. And the watershed involved is the San Gabriel Mountain and River watershed.

All the cities involved in the case are located downstream of the water recharge basins. Long Beach is located near the mouth of the San Gabriel River to the Pacific Ocean. A map of the cities along the San Gabriel River can be found here[6].

The Defendants

The defendants (respondents) are three cities and one sub-regional water agency: the cities of Cerritos, Downey and Signal Hill, together with the Central Basin Municipal Water District. The Central Water Basin is obviously located near the center of the land surface of the Los Angeles urban basin.

While there is no sex involved in this case, there is bureaucratic bigamy and alleged robbery: all of the parties to the case share the same underground water basin. In fact, the Water Replenishment District was created to refill the Central and West Coast underground water storage basins. There has been a history of court cases in the Central Basin alleging “overdrafting.” That is water terminology for “highway robbery.”

The History of the Central Basin Water Wars

The Central Basin has a 277-square-mile underground footprint. If the basin were square shaped, it would comprise an area of about 16.5 miles by 16.5 miles. The Central Basin serves city water departments, unincorporated areas, private water companies, school districts, electric utilities and landowners. The Central Basin Water District sells treated water to cities and others within its regional service area. Like the movie “Chinatown,” water is a many-layered story. There are no murders but there are plenty of complex water wars.

Going back to 1965, a court ordered that 500 parties having water rights in the Central Basin were subject to limits as to how much water they could take to prevent overdrafts.

In 2001, several interested parties sought unused storage space in the Central Basin. A court appointed the California Department of Water Resources to serve as “watermaster,” or water traffic cop. But at that time, the court rejected the legal notion that the right to extract water creates a concurrent right to store water.

By 2009, another group of water pumpers bubbled up. They filed a court action to use 330,000 acre-feet of “dewatered space” in the Central Basin for future water storage. This would be enough water for about 660,000 households per year. This action sought even more layers of complexity: three “watermasters” were to be appointed.

The trial court issued an order on July 7, 2010. The order said it only had authorization to apportion water rights and not rights to unused capacity space in the Central Basin. Additionally, the court believed it could not appoint “watermasters” over unused space in the basin that held no water today. The Water Replenishment District of Southern California is appealed the ruling.

The Current Court Ruling

On Jan. 18, 2012 the State Appellate Court ruled that the trial court: 1) had authority to allocate future storage in the Central Basin; 2) had jurisdiction over water transfers between the Central and nearby West Coast Basins; and 3) was not prohibited from appointing a “watermaster” over unused space in the Central Basin. The court additionally ruled that the Central Basin Water District might also be able to serve as “watermaster.”

The defendants[7] — the cities of Cerritos, Downey and Signal Hill — contended: 1) their costs would be increased if others were given the right to lease unused capacity in the Basin; 2) over-drafting of the Basin could result if new “wet water” was not put in first; and 3) there was a threat the appointed watermaster could try to merge the Central and West Coast Basins. The Central Basin did not want a proverbial “shotgun marriage” to result over the issue of renting a room to the unwanted bastard child of unused basin capacity.

Presumably, the above issues can be heard and adjudicated now that the jurisdictional issues have been clarified.

Enormous Implications

The timing of this case has enormous implications for what is happening statewide. The Delta Stewardship Council[8] appointed by the State Legislature is about to put into place widely encompassing laws that could usurp powers from local water districts. Local water agencies would no longer be able to do anything that adversely impacted the Sacramento Delta. The Delta is where Southern California gets most of its imported water supplies. Conceivably, local water departments might not be able to issue any new water permits or “will serve” letters to real estate developers if that meant using more imported Delta water.

David O. Powell, the former chief engineer of the San Diego Office of the State Department of Water Resources and the Alameda Water District, said he believed the proposed Delta Plan would result in cutting water allocations to Southern California in half.

This is despite Southern California using about the same amount of water it used 25 years ago, even with 35 percent more population. Through conservation, Southern California has already given up about 1 million acre-feet of water per year to the Delta ecosystem. That is enough water for about 2 million households or 4.5 million people. Yet the Delta Stewardship Council wants to reduce water use by and additional 20 percent by the year 2020.

State and regional water agencies have shown an inability to bring more water to Southern California without huge, costly infrastructure projects, such as: the proposed Peripheral Canal that would route water around the Delta and/or the proposed $11.1 billion water bond. Both of these projects would pinch the already deficit-plagued state budget. There are matching fund requirements in the proposed state water bond. Thus, the real cost of the proposed water bond may be about $18 billion. The cost of the Peripheral Canal is estimated to cost $13 billion, or $23.5 billion with bond interest costs.

Consequently, local water districts and cities are going to have to find a way to capitalize on the unused storage capacity in the eight underground water basins in Southern California[9]. They may be compelled to contract for some of their own water supplies instead of depending on more imported water from regional water wholesalers. This could mean water transfers from recycled water, from the new Cadiz water basin in the Southern California desert, voluntary purchases of water from farmers, desalinated ocean water or the development of new water resources. This will require a much more open water conveyance and storage system with reasonable transfer costs than the present semi-socialized system with many trade barriers.

So the outcome of the Water Replenishment District versus the city of Cerritos case may have huge consequences for Southern California’s cities and economy.

[10]Economic Homicide?

[10]Economic Homicide?

To add another subplot to the story, Assembly Bill 375[11] — the anti-urban sprawl bill passed in 2008 — would divert future population growth to the coastal urban areas. But this may result in “no growth” if the water spigot from imported water from the Delta is simultaneously shut off. This could kill off an economic recovery.

So maybe the above-mentioned court case is like the movie “Chinatown” and will involve murder — economic homicide — anyway.

Or it may have a wedding and happy ending: economic reproduction if local water agencies and city water departments are allowed to contract for future water and deposit it in fertile underground local water basins.

A sequel to “Chinatown” came out in 1990, called “Two Jakes[12].” It wasn’t as good, even though it starred Jack Nicholson and another great actor, Harvey Keitel.

It’s time for a better sequel. Call it, “Central Water Basin Blues.” Jack Nicholson could star once more, this time with Arnold Schwarzenegger, now an actor again after his stint as governor. As in the original “Chinatown,” and as with the real California, reality and fiction would blend on the celluloid.

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Chinatown-3.jpg

- Chinatown: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinatown_%281974_film%29

- Kevin Wattier: http://www.presstelegram.com/breakingnews/ci_19786914

- Water Replenishment District of Southern California versus the City of Cerritos: http://www.leagle.com/xmlResult.aspx?xmldoc=In%20CACO%2020120118033.xml&docbase=CSLWAR3-2007-CURR

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Chinatown-Faye.jpg

- here: http://www.centralbasin.org/serviceArea.html

- defendants: http://kbtlawyers.com/news-GroundwaterStorage.html

- Delta Stewardship Council: http://www.calwatchdog.com/2012/01/13/delta-council-meetings-flood-state/

- eight underground water basins in Southern California: http://www.crinfo.org/booksummary/10052/

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Chinatown-Nicholson1.jpg

- Assembly Bill 375: http://greeneconomics.blogspot.com/2009/02/interesting-e-mail-on-water-and.html

- Two Jakes: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0100828/

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2012/01/29/water-wars-flood-l-a-central-basin/