Bill would protect cell phone privacy

by Joseph Perkins | July 13, 2012 9:27 am

[1]July 13, 2012

[1]July 13, 2012

By Joseph Perkins

Is one of every 186 cell phone users a criminal suspect?

One might think so in the wake of the revelation this week, in a congressional report[2], that law enforcement requested data last year from Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile and other carriers on the calls, text messages and, perhaps most ominously, location of more than 1.3 million of the nation’s 234 million cellular customers.

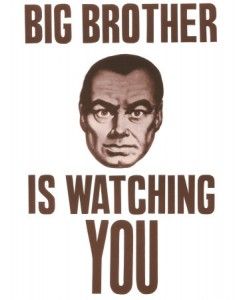

The growing threat to privacy rights posed by increased police use of secret and, in many cases, warrantless cell phone surveillance underscores the importance of legislation, the California Location Privacy Act, that would require law enforcement to secure a search warrant before accessing location information from any electronic device.

The measure, SB 1434[3], was approved last week by the Assembly Committee on Public Safety, which followed its approval back in May on the Senate floor. Particularly noteworthy is that the bill, authored by Sen. Mark Leno, the San Francisco liberal, won the support of not only his fellow Democrats, but also Republicans.

That may be attributable in part to questions that remain after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled this past January that law enforcement’s secret attachment of a GPS device on a vehicle constitutes a “search” and therefore requires a search warrant; but it left unsettled whether the same ruling applies to GPS location tracking by way of cell phone.

The U.S. Justice Department maintains that the high court’s ruling, United States v. Jones[4], does not apply to mobile devices “because there is no trespass or physical intrusion on a customer’s cell phone,” thus no need for law enforcement to obtain a warrant before asking wireless carriers to turn over customer data.

State action

Lawmakers in Sacramento see things differently. The majority believe that the constitutional protection against warrantless searches applies not only to cases of trespass or intrusion, but also to secret cell phone surveillance.

And they have codified that in the proposed California Location Privacy Act, which makes it clear to both “government entities” and wireless service providers that a probable cause warrant must be obtained before compromising a cell phone user’s privacy.

The measure would allow exceptions to be made in cases in which a cell phone user has requested emergency services or law enforcement reasonably believes there is immediate danger of death or serious injury to a person or persons.

The one major shortcoming of Leno’s otherwise laudable legislation is that imposes no requirement on cell phone carriers here in California to provide annual reports on the number of law enforcement requests the receive to spy on their cell phone customers.

CTIA-The Wireless Association, a trade group representing the wireless telecommunications industry, sent a letter to Leno[5] this past April opposing such a requirement, arguing that it would “unduly burden wireless providers,” and that it was doubtful that compliance “would best serve wireless customers.”

Yet, the industry already keeps copious records on data requests for purposes of billing law enforcement for those requests. It could easily compile those records into an annual report to the state.

And as to what best serves wireless customers, reporting or not reporting annual law enforcement requests for cell phone records, most of us almost certainly would prefer transparency.

For while we understand that law enforcement needs certain latitude to apprehend criminals, including use of secret cell phone surveillance, safeguards must be in place to ensure that our privacy rights are not routinely trampled upon.

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/2011/07/18/stopping-carte-blanche-cell-phone-searches/big-brother-is-watching-you4-12/

- a congressional report: http://markey.house.gov/press-release/markey-queries-justice-dept-about-mobile-phone-data-requests-privacy-protections

- SB 1434: http://info.sen.ca.gov/pub/11-12/bill/sen/sb_1401-1450/sb_1434_bill_20120628_amended_asm_v95.pdf

- United States v. Jones: http://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/11pdf/10-1259.pdf

- sent a letter to Leno: https://www.aclunc.org/docs/technology/cita_opposes_sb_1434_leno.pdf

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2012/07/13/bill-would-protect-cell-phone-privacy/