Higher down payments could be compromise Prop. 13 reform

by CalWatchdog Staff | January 2, 2013 9:18 am

[1]Jan. 2, 2013

[1]Jan. 2, 2013

By Wayne Lusvardi

Could simply requiring higher down payments on home loans be a compromise reform of Proposition 13?

The Democratic Party supermajority in the state legislature is presently pushing for reforms of Proposition 13[2], the 1978 initiative that limits property tax increases to 2 percent per year until a property resells.

Some of the legislature’s proposed reforms include eliminating Prop. 13 for commercial properties and lowering the voter threshold for school parcel taxes to 55 percent from the current two-thirds.

But there may be a better way.

The culprit involved in state budget deficits is not Prop. 13. It is low down-payment requirements and interest rates on home purchases combined with the effects of slow-growth management and environmental laws. Growth-management laws cause the excessive housing booms and busts that throw state and school budgets out of balance, as well as causing upside-down home values.

Bogeymen don’t cause the problem

During recessions, a collective rain dance ritual to bring taxes from heaven occurs in California. Part of this ritual is for local school districts to protest[3] projected budget cuts that end up never actually laying off teachers. Teachers are guaranteed 43 percent of the state general fund budget under Proposition 98[4]. Politicians know voters will vote for school children before they will vote for health and welfare programs. Any tax increases are money laundered to health and welfare programs.

It is sales and income tax revenue flows that are most prone to sudden declines in California. Nonetheless, Prop. 13 is typically blamed for California’s budget deficits. But Prop. 13 has a built-in circuit breaker[5] that prevents large increases or decreases in property taxes in any one year.

Democratic politicians also claim commercial properties are under-taxed due to Prop. 13 tax loopholes. But it has recently come to public awareness that reforming Prop. 13 is not needed[6] to close the alleged loophole in majority ownership transfers of commercial properties. Large commercial property owners are just used as bogeymen for eventually getting rid of Prop. 13 altogether on both commercial and residential properties. Ending Prop. 13 for commercial properties mainly would affect struggling small businesses that comprise 97 percent of all businesses in the state.

Prop. 13 is a policy that lessens the shock of higher property taxes during economic housing booms and lower taxes during housing busts. This prevents the proverbial widow from being thrown on the street for an inability to pay greatly increased property taxes during booms. And it prevents huge declines in property tax revenues for public schools in any one year.

Conversely, there is a manufactured erroneous media perception that tax revenue shortages during economic recessions are the result of Prop. 13 constraints against large property tax hikes during housing booms. Prop. 13 critics ignore the capital gains tax revenue from the dot-com, Facebook and other bubbles. But capital gain tax revenue is highly unpredictable for budgeting.

There is also the problem of upside-down home values as a result of crashes following housing price booms. Politicians may be averse to raising property taxes on homes where mortgages exceed home values by as much as 20 to 50 percent.

Low Down Payments with Slow-Growth Plans are Main Cause

It is the toxic combination[7] of slow-growth and smart-growth plans and environmental impact reports with low down payment mortgages that help bring about abnormal booms and busts in California’s real estate market.

Homeowners don’t want to be subjected to wild increases in property taxes that displace widows and moderate-income homeowners. Thus, there is Prop. 13 to protect them.

But state government and local school districts only want budget surpluses from housing booms and not deficits from the busts. The problem is that government doesn’t want to see that it is complicit in creating the deficit problem. Instead, they always want to blame Republicans. But there are no more Republicans to blame because their power has become so small. And Republicans aren’t to blame in the first place.

Democratic Party central planners want to reserve central cities and Lake Tahoe[8] for the wealthy or politically connected lower class by “performance zoning”[9] and design commissions. In California, it is “Petaluma style”[10] growth management. Growth management drives the politically unconnected out to the urban fringe, “edge cities,”[11] and transitional farmland for new housing subdivisions. Housing planners call this the “Push Down-Pop Up” phenomenon. Thus, growth management results in stable or rising property values in San Francisco but boom and bust cycles in Fresno, Stockton and the Inland Empire.

Slow-growth plans and environmental clearances create inflated home prices by restricting the supply of available land. Low interest rates and low down payments add fuel to this fire and cause home prices to rise beyond what incomes can support. This creates a vicious cycle where homeowners need continual booms to offset their over-mortgaged housing that incomes cannot support.

California homeowners become addicted to voting for policies that promote housing booms to be able to sell their homes for an appreciated value. And booms push property tax revenues under Prop. 13 up faster than money inflation. Prop. 13 reformers never protest the windfalls from the hyper-inflation of housing.

As shown in the table below, the average home loan down payment in California is 13.25 percent. This comes nowhere near the 43.76 percent real home price decline reported by the Federal Housing Finance Agency from 2006 to 2009.

Real Home Price Downturns and Down Payment Percentages

| Area | Median Percent Real Decline2006 to 2009 | Recovery Duration1975-2009 | Average Down Payment in2009 |

| United States | -30.5% | 20.75 years | 12.29% |

| California | -43.76% | 6 years | 13.25% |

| Source: A Brief Examination of Previous House Price Declines, Federal Housing Finance Agency, 2009[12].“Down Payment on a California Home Averages 13.25%,”[13] O.C. Register, 12/14/2011 | |||

San Francisco has few “no down payment” loans; Fresno and the Inland Empire have a lot. Home values outside coastal growth management cities and counties are lower the further out you go: “drive till you qualify.” Low interest rates and low down payments help home buyers in coastal areas afford bigger houses. The rich get richer and the poor get upside-down mortgages. And state and local governments and school districts get budget deficits during recessions.

Bubbles

Housing bubbles are manufactured in California, not on Wall Street. One in every 173 homes in California was in foreclosure[14] in 2009; only 1 in 1,000 in Texas.

A sociological law is that beliefs tend to hang together. It is likely the same Democratic politicians and voters that embrace growth management, environmental clearances and affordable housing policies also support reforming Prop. 13. But there is no awareness that such policies create the “roller coaster”[15] housing economy that ends up making tax revenues so changeable and result in government budget deficits.

If Democrats in full power in California were serious about reforming Prop. 13, they would leave it alone — except for requiring much larger housing down payments in the entire state. Doing so would push inland property values in the direction of the stability already enjoyed by coastal properties.

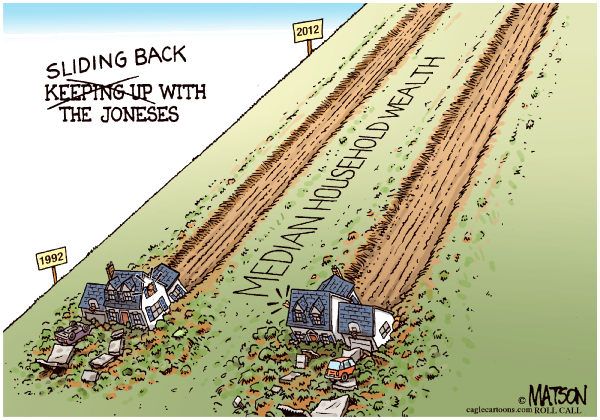

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/2012/12/18/starving-ca-govt-begins-to-devour-itself/housing-wealth-cagle-cartoon/

- reforms of Proposition 13: http://www.sfexaminer.com/local/2012/12/san-francisco-legislators-are-eager-reform-proposition-13-and-related-tax-policies

- protest: http://www.scpr.org/news/2010/03/04/12592/thousands-gather-protest-california-education-cuts/

- Proposition 98: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_Proposition_98_(1988)

- circuit breaker: http://www.calwatchdog.com/2011/07/08/prop-13-circuit-breaker-halts-bigger-tax-losses/

- reforming Prop. 13 is not needed: http://www.calwatchdog.com/2012/12/18/reality-could-stifle-prop-13-reform-attempts/

- toxic combination: http://www.amazon.com/American-Nightmare-Government-Undermines-Ownership/dp/1937184889/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1356822313&sr=8-1&keywords=american+nightmare+o%27toole

- Lake Tahoe: http://www.feinstein.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/textonly/issues?p=restoring-lake-tahoe

- “performance zoning”: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoning

- “Petaluma style”: http://www.cp-dr.com/node/962

- “edge cities,”: http://www.amazon.com/Edge-City-Life-New-Frontier/dp/0385424345

- A Brief Examination of Previous House Price Declines, Federal Housing Finance Agency, 2009: http://www.fhfa.gov/webfiles/2918/PreviousDownturns61609.pdf

- “Down Payment on a California Home Averages 13.25%,”: http://lansner.ocregister.com/2011/12/14/down-payment-on-a-calif-home-averages-13-25/155466/lendingtreegraphiccropw/

- foreclosure: http://www.amazon.com/American-Nightmare-Government-Undermines-Ownership/dp/1937184889/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1356886693&sr=1-2&keywords=american+nightmare

- “roller coaster”: http://www.usc.edu/schools/price/research/popdynamics/pdf/2012-Update_Myers-etal_California-Roller-Coaster.pdf

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2013/01/02/higher-down-payments-could-be-compromise-prop-13-reform/