Legitimacy, not consensus, is key to Delta modernization

by CalWatchdog Staff | May 3, 2013 10:10 am

[1]May 3, 2013

[1]May 3, 2013

By Wayne Lusvardi

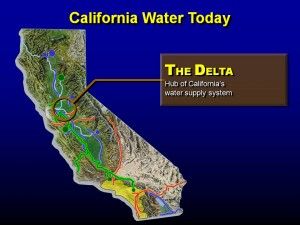

Do we care whether there is a consensus about what to do with the so-called natural resources of the Sacramento Delta among scientists and interest group “stakeholders” in California? The Public Policy Institute of California thinks so with a new study funded by the Bechtel Corporation[2], the largest construction and engineering company in the U.S., “Stress Relief: Prescriptions for a Healthier Delta Ecosystem.”[3]

But what good is a general agreement among “stakeholders” and scientists who all stand to benefit in some way from re-engineering the “ecosystem” of the Sacramento Delta? This persuasion technique is called an appeal to authority, and is considered a logical fallacy[4].

A consensus of experts and stakeholders won’t help justifying the legitimacy of whether it is fair to ask water ratepayers and farmers to pay for possibly less water from the Delta; or whether statewide taxpayers should pay for making the Delta more livable for popular fish at the expense of less popular fish.

“Everyone tries to make water flow to his mill” — Arab proverb

The PPIC surveyed 225 “delta-based interested parties,” “water export interests,” “fishing and recreation interests,” “upstream water agency interests,” and “Federal and state officials,” to determine if they agreed with scientists about what to do with the Delta’s native fish species. This report is part of ongoing research that has generated five previous reports on the Delta “ecosystem,” which basically means where fish live.

It is interesting to note that the report describes 95 percent of the 700,000 acres of former tidal wetlands in the Delta as unnatural resources: below sea level “rock-rimmed agricultural islands” protected by levees.

The new PPIC study found there is a consensus among stakeholders and scientists when it came to “stressor impacts” in the Delta:

* Upstream water diversions (for farming and flood control);

* Urban and agricultural water discharges of pollutants;

* So-called invasive species;

* Harmful fish management practices;

* Harmful land alterations.

The experts and stakeholders agree these “stressors” should be reduced or eliminated.

However, scientists expressed that water discharges, bad fish management, and invasive species were more important than did the stakeholders. And some stakeholders didn’t agree with scientists on the priority of actions to be taken. Scientists wanted to control habitats, reduce water flow variability, and manage upstream flows into the Delta more than stakeholders did. While stakeholders preferred to reduce discharges, engineer water diversions, and better manage farm harvests. This doesn’t tell us much except that farmers would prioritize what they can manage and scientists would prioritize what farmers don’t manage.

A case of “Delta Stress”

The end of the PPIC report encourages building greater public support for a “healthier Delta ecosystem.” The PPIC researchers use therapeutic language borrowed from the “health, lifestyle, and environmental” movement in California. But fixing the Delta is an issue of cultural values more than it is simplistically reducing what might humorously be called “Delta stress.” The Delta ecosystem can operate:

* As a cold-water Delta for salmon;

* A warmer-water Delta for bass and catfish;

* An ocean water Delta for halibut, striper, perch or shellfish;

* As a combination of all three.

Calling a salmon-less or smelt-less Delta “unhealthy” is a cultural value judgment and political choice, not a purely scientific issue.

Consensus among experts and stakeholders isn’t going to generate greater legitimacy for fixing the Delta’s natural resources. Consensus and legitimacy are not the same thing.

Scientists, farmers, fishermen, water agencies and government bureaucrats are not going to agree on priorities. As the Los Angeles Times summarized the PPIC study: “[T]he consensus seems to be, let somebody else fix the Delta.”[5] There is nothing new in this finding. The rule in California is everybody wants public goods but doesn’t want to pay for them.

Socializing — or spreading the costs — to a large number of taxpayers creates the perception that public goods are effectively free to those few who benefit the most from them. That is often why stakeholders prefer government solutions to markets. Markets impose the real costs on those who benefit the most from them (“user pays”).

Shhh! The Delta needs modernizing

“Restoring the Delta” is a misnomer because bringing back sunken farmland and greater numbers of popular salmon fish during dry years isn’t necessarily going to provide a fix for the Delta. Salmon thrive during wet years anyway[6]. And reverting the Delta back to an “inland sea” that nearly cuts the state in two parts during wet years is not a fix either. That is why the project to fix the Delta’s natural resources is accurately called “the Bay Delta Conservation Plan,” or “BDCP” for short. The natural resources of the Delta need to be “conserved,” not “restored.”

The Delta needs modernizing, although that word is not as appealing to the public. It is easier to sell “restoration” or “conservation” than modernization. Ever since the coming of monopolistic railroads to California[7], the state hasn’t seemed to like modernization. It has preferred an image of returning to some bucolic rural past, but without all the droughts and flood damage that came with that. Like it or not, the Delta needs modernizing to meet the co-equal goals of the BDCP of greater water reliability and enhanced fish habitat.

Voters and ratepayers would have to pay about $53 billion[8] for the whole package of Delta improvements: tunnels, habitat re-creation, levee repairs, two new reservoirs and bond interest costs. Statewide taxpayers would pay for the Delta ecosystem and levee improvements; and farmers and Southern California ratepayers would pay for the proposed Delta Tunnels.

CA not short on water, but water conveyance legitimacy

What is more important than a consensus of experts and stakeholders is whether statewide voters are going to vote for the $11 billion California Water Bond scheduled to be on the ballot next year. Also more important is whether Southern California water ratepayers are going to accept higher water rates to provide possibly less but more reliable water. Water unreliability has been caused by court-ordered shutdowns of contracted water deliveries to increase popular fish species to the Delta at the expense of unpopular fish species.

The real issue for voters and water ratepayers isn’t a manufactured “consensus,” but whether the massive funding for the project is justifiably legitimate. Legitimacy, not consensus or money[9], is more important in any war, even a protracted water war between Northern and Southern California.

- [Image]: http://www.calwatchdog.com/?attachment_id=40747

- Bechtel Corporation: http://www.bechtel.com/

- “Stress Relief: Prescriptions for a Healthier Delta Ecosystem.”: http://www.ppic.org/main/publication.asp?i=1051

- logical fallacy: http://www.nizkor.org/features/fallacies/appeal-to-authority.html

- “[T]he consensus seems to be, let somebody else fix the Delta.”: http://www.latimes.com/news/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-sacramento-san-joaquin-delta-ppic-20130429,0,6451884.story

- thrive during wet years anyway: http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/dailydish/2012/05/california-salmon-start-their-comeback.html

- monopolistic railroads to California: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Octopus:_A_Story_of_California

- $53 billion: http://www.calwatchdog.com/2012/07/30/southern-califiornias-new-pact-with-the-delta-water-devil/

- Legitimacy, not consensus or money: http://www.calwatchdog.com/2013/04/30/ca-delta-water-war-being-won-by-legitimacy-not-money/

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2013/05/03/legitimacy-not-consensus-is-key-to-delta-modernization/