Rainfall study contradicts CA water policy

by Wayne Lusvardi | August 16, 2013 8:47 pm

In the mid-1970s, it was common for many Santa Barbara County communities to deny water meters to limit growth and development. Santa Barbara experienced periodic droughts up until 1991, when it finally built a pipeline connecting to the State Water Project’s California Aqueduct[1].

In the mid-1970s, it was common for many Santa Barbara County communities to deny water meters to limit growth and development. Santa Barbara experienced periodic droughts up until 1991, when it finally built a pipeline connecting to the State Water Project’s California Aqueduct[1].

However, a 2012 climate change study entitled “When It Rains It Pours,”[2] by Environment California’s Research Policy Center, suggests it might be better for California to build new water storage facilities in Santa Barbara than in the Sacramento Delta. The reason: From 1948 to 2011, extreme storms increased south of the Bay-Delta by 35 percent and decreased north of the Bay-Delta by 26 percent. Santa Barbara in particular saw a 72 percent increase in extreme storms.

This is a striking finding. It’s one that some might think should affect public policies dramatically, given that polls showing overwhelming public support to address climate change[3]. And this isn’t speculative, based on expectations on what will happen as carbon builds up in the atmosphere. It’s already happened.

Given all the billions of dollars being spent by California in identifying and combating climate change[4], it is inconsistent that state water planners apparently can’t keep up with basic changes in rainfall patterns. There has been a 60-year shift in Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties, where there are not enough reservoirs to capture rainfall for statewide needs.

Practical approach on water preferable

But should state water planning be based on this shift in rainfall patterns, which may or may not be a historical fluke? In the larger picture, should state water planning be based on anticipated-but-not-yet-occuring vast changes in weather patterns? And in general, should we make plans that assume an expertise about how the climate works that we don’t necessarily have?

A sober evaluation suggests that practical considerations should matter most — not knee-jerk reactions to new data or abstract theories based on assumptions of near-omniscience about the physical world.

This becomes clear when thinking about the state’s present approach and how it might change if the recent regional rainfall study were considered definitive.

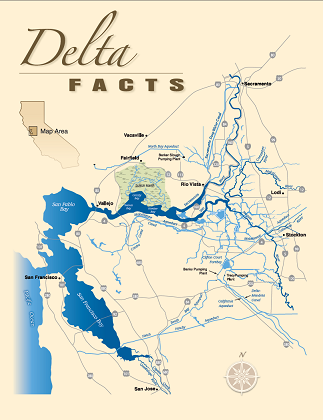

Putting any new water storage in Santa Barbara runs against current planning efforts to undertake a massive $53 billion re-engineering of the Sacramento Delta[5]. State water planners have even named their effort to build new future dams the “North of the Delta Offstream Storage Investigation Project (NODOS).”[6]

Putting any new water storage in Santa Barbara runs against current planning efforts to undertake a massive $53 billion re-engineering of the Sacramento Delta[5]. State water planners have even named their effort to build new future dams the “North of the Delta Offstream Storage Investigation Project (NODOS).”[6]

After investigating 52 potential new reservoir locations, state and federal planners have focused on five surface water storage sites north of or near the Delta:

- — Shasta Lake Enlargement in Northern California

- — In-Delta storage including expansion of Los Vaqueros Reservoir and enlargement of Millerton Lake.

- — The proposed Sites Reservoir[7] would be located north of the San Francisco Bay on a tributary to the Sacramento River. The Temperance Flat[8] dam site would be located on the eastern side of the Delta in the Sierra Nevada mountain chain.There are only two reservoirs south of the Delta that are connected to the California Aqueduct: the San Luis Rey Reservoir in Merced County[9] some 300 miles north of Santa Barbara and Lake Cachuma[10] (elevation 778 feet above sea level) located about 20 miles distant and at an elevation 729 feet higher than Santa Barbara (49 feet above sea level).

The rain map isn’t what it used to be

A problem with such climate studies is that the 50-year rainfall concentration map of Santa Barbara County[11] shows that Goleta and the city of Santa Barbara are where most of the rainfall occurs. Goleta and Santa Barbara are at low coastal elevations where there is little to no practical possibility to reverse gravity flow water back into the California Aqueduct.

The Coastal Branch of the California Aqueduct[12] and Central Coast Water Authority pipeline extends to Lake Cachuma in Santa Barbara located some 20 miles upland from the coast. A reverse-flow pipeline and/or canals would have to lift any coastal rainwater 729 feet in elevation and build a parallel pipeline 143 miles to transport water back into the California Water Aqueduct for use by Southern California cities.

The Central Coast Branch of the State Water Project[13] delivers only 39,078 acre-feet of water to coastal communities in San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties. That is only 0.09 percent of the 43.1 million acre-feet of water[14] delivered to cities and farms from the State Water Project in an average rainfall year. An acre-foot of water is enough to supply about two urban households with water for one year.

Even if Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties were to return their full share of imported water to the State Water Project, it would be mostly inconsequential.

Logistical approach beats ideological one

This underlines California’s reality: Our water planning problem is local, regional, logistical and practical. It is not — or at least it shouldn’t be — global and ideological.

Perhaps journalist Theodore White[15] summed up California’s water planning best when he wrote, “A liberal is a person who believes that water can be made to run uphill. A conservative is someone who believes everybody should pay for his water. I’m somewhere in between: I believe water should be free, but that water flows downhill.”

Gov. Jerry Brown has an entire website[16] dedicated to refuting those who attack climate change theory. In particular, Gov. Brown attacks climate change “deniers.”[17] Public opinion polls reportedly indicate 77 percent of Californians back the climate change fight[18]. But basing statewide water planning on confident assumptions that we know how the weather will change would be yet another “Governor Moonbeam”[19] idea.

- connecting to the State Water Project’s California Aqueduct: http://www.countyofsb.org/pwd/water/downloads/StateWaterandBasinMgmtPlans05.pdf

- “When It Rains It Pours,”: http://www.environmentcaliforniacenter.org/reports/cae/when-it-rains-it-pours

- polls showing overwhelming public support to address climate change: http://blogs.sacbee.com/capitolalertlatest/2013/07/californians-back-reducing-emissions-fighting-climate-change-poll.html

- billions of dollars being spent by California in identifying and combating climate change: http://www.forbes.com/sites/larrybell/2011/08/23/the-alarming-cost-of-climate-change-hysteria/

- $53 billion re-engineering of the Sacramento Delta: http://calwatchdog.com/2012/07/30/southern-califiornias-new-pact-with-the-delta-water-devil/

- North of the Delta Offstream Storage Investigation Project (NODOS).”: http://www.water.ca.gov/storage/northdelta/index.cfm

- Sites Reservoir: http://www.water.ca.gov/storage/docs/NODOS%20Project%20Docs/Sites_FAQ.pdf#Question_3

- Temperance Flat: http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-030910-me-water_dam-g,0,7077891.graphic

- San Luis Rey Reservoir in Merced County: http://blogs.sacbee.com/capitolalertlatest/2013/07/californians-back-reducing-emissions-fighting-climate-change-poll.html

- Lake Cachuma: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Cachuma

- 50-year rainfall concentration map of Santa Barbara County: http://www.countyofsb.org/uploadedImages/pwd/Water/50%20YR%20Rainfall%20-%202011.jpg

- Coastal Branch of the California Aqueduct: http://www.water.ca.gov/recreation/brochures/pdf/Coastal_Branch_Brochure.pdf

- Central Coast Branch of the State Water Project: http://www.ccwa.com/docs/History1.pdf

- 0.09 percent of the 43.1 million acre-feet of water: http://www.water.ca.gov/swp/watersupply.cfm

- Theodore White: http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/keywords/water_6.html#ut3uTiMEC4HIYAwm.99

- entire website: http://www.opr.ca.gov/s_denier.php

- “deniers.”: http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/california-politics/2012/08/jerry-brown-sets-sights-on-climate-change-denialists.html

- 77 percent of Californians back the climate change fight: http://blogs.sacbee.com/capitolalertlatest/2013/07/californians-back-reducing-emissions-fighting-climate-change-poll.html

- “Governor Moonbeam”: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/07/weekinreview/07mckinley.html?_r=0

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2013/08/16/rainfall-study-contradicts-ca-water-policy/