SB 365 aims at limiting tax credits

by Dave Roberts | August 27, 2013 9:56 am

[1]

[1]

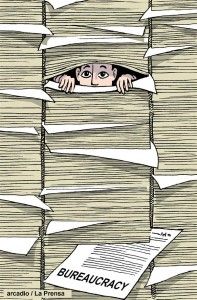

The California Tax Code[2] is a monster. Just the first 136 sections of the code fill up 202 pages with more than 100,000 words. The entire code contain 60,709 sections. If those first 136 sections are indicative, the entire code contains more than 90,000 pages and in excess of 45 million words.

One of the contributors to the length and complexity of California’s tax law are the numerous tax credits built into it. There are scores of tax carve-outs for favored constituencies, for groups deemed to need help, and to incentivize activities deemed in society’s interest.

The largest credit is the mortgage interest deductions, for which taxpayers got to keep an estimated $4.4 billion that would have gone to the state in the 2012-13 fiscal year. Others deductions include the exclusion for employer contributions to pension plans ($4 billion), employer contributions to accident and health plans ($3.6 billion), Social Security benefits ($2.6 billion) and the charitable contribution deduction ($1.6 billion). Tax credits are also provided for low-income renters, the blind, low-income housing expenses, first-time home buyers, motion picture companies, student loan interest, clergy housing and on and on.

While the credits are a boon to the recipients, they have denied the state tax money that some politicians would like to get.

“Our current tax preference portfolio now exceeds $47 billion, equal to half of our total revenue,” said Sen. Lois Wolk[3], D-Davis on the Senate Floor April 22, speaking in support of her bill, SB 365[4]. “This bill requires that all future bills that create tax preferences state the goals of the preference and identify specific indicators and data measurement to see if it works. It will require a 10-year sunset on these bills. SB 365 will ensure that the Legislature uses the public dollar wisely. The bill affects no current tax benefits, only future ones.”

Chamber calls it a ‘job killer’

There was no discussion or debate, and the bill passed the Senate 22-11 along party lines. But the California Chamber of Commerce[5], which has placed SB 365 on its list of “job killer” bills[6], is hoping to head it off in the Assembly.

SB 365 “creates uncertainty for California employers making long-term investment decisions by requiring tax incentives end 10 years after their effective date,” the Chamber states on its website[7]. “When businesses choose to locate in a state, factors such as the availability of a skilled workforce, infrastructure, regulatory environment, and tax structure all play a significant role. Businesses evaluate whether they can rely on these factors to remain relatively stable and consistent in the long term.

“Furthermore, for capital-intensive industries like manufacturing and research and development, investment decisions are made many years into the future. The ability for corporate decision makers in these industries to plan anticipated costs over a span of many years is an important factor when determining locations for these investments. Establishing an arbitrary maximum 10-year sunset puts the long-term viability of any credit in jeopardy and, in many cases, could ultimately render the credit’s value useless in a company’s final decision on a location.”

Instead of an automatic sunset, the Chamber wants future tax credits “to be evaluated on their own merit. A reasonable sunset should be applied only if appropriate.”

Justification for tax credits

The Franchise Tax Board’s[8] 2011 Tax Expenditure Report[9] provides background on tax credits, which the government calls “expenditures” even though the state is simply allowing people and businesses to keep some of the money they earn rather than hand it over to the government.

“There are two primary policy motivations for adopting tax expenditures,” the report states. “The first is to move towards a more equitable tax system by providing relief to taxpayers facing a monetary cost due to their circumstances in life. The second is to provide taxpayers with incentives to alter their behavior.”

For example, carpooling has the societal benefit of helping reduce traffic congestion. So it may be in government’s interest to provide a tax incentive for carpooling to motivate those who would otherwise drive to work alone to instead share their commute.

“Thus, a credit for carpooling will allow the person who chooses carpooling to reap some of the social benefit of carpooling,” the report states. “This will increase the likelihood of a decision to carpool. In such a situation, if the net social benefit from carpooling is positive, the fact that the tax system alters private decisions (or violates tax neutrality) is actually good. Policy makers must be careful, however, to ensure both that tax incentives induce desired behaviors and that they do not induce too much of the desired behaviors.”

Common concerns about tax credits are that they may:

* Necessitate an increase in tax rates or a cut in expenditures.

* Complicate the tax code.

* Induce undesirable behavior from taxpayers. For example, if a tax credit is set too high, it might divert investment from other projects that would be more beneficial to the economy.

* Provide expensive windfalls to some taxpayers without furthering the intended policy goals.

Clumsy at best

And tax credits are clumsy mechanisms at best. The report lists numerous alternatives that might achieve the same policy objectives:

* Instead of providing targeted tax credits designed to improve the general economy, the same effect could be achieved by reducing overall tax rates.

* Tax credits aimed at spurring investment in specific activities, industries, or geographic locations could be replaced with direct government loans, loan guarantees or rate subsidies.

* Tax credits can be replaced with government mandates. For example, the Low-Income Housing Expenses Credit could be replaced with requirements that lenders or developers divert a portion of their economic activity to the low-income market.

* Almost any tax credit could simply be replaced with a direct expenditure. For example, instead of offering a Child Adoption Expense Credit, California could make direct payments, equivalent to the tax savings available under the credit, to couples who adopt children.

“There are potentially many good reasons for using tax expenditures within a tax system,” the report concludes. “However, policymakers should give careful thought to the reasons why the tax expenditure is needed, and the potential adverse consequences of adopting or retaining the tax expenditure.”

If SB 365 is approved in the Assembly and signed by Gov. Jerry Brown, there is a distinct possibility that it won’t achieve its 10-year automatic sunset objective. That’s because it would in effect allow the current Legislature to dictate to future legislatures the terms of future tax credit legislation.

“[E]ven if a general sunset requirement were included in statute, there would be nothing to prevent a future Legislature from enacting an open-ended tax expenditure ‘notwithstanding’ the statutory prohibition,” the bill’s legislative analysis concludes. “Courts have long held that one legislative body may not limit or restrict its own power or that of subsequent Legislatures, and the act of one Legislature may not bind its successors. In practical terms, it means that subsequent Legislatures are under no legal obligation to comply with the provisions of this bill.”

- [Image]: http://calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/bureaucracy-cagle-Aug.-27-2013.jpg

- California Tax Code: http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/.html/rtc_table_of_contents.html

- Sen. Lois Wolk: http://sd03.senate.ca.gov/

- SB 365: http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/13-14/bill/sen/sb_0351-0400/sb_365_cfa_20130626_165715_asm_floor.html

- California Chamber of Commerce: http://www.calchamber.com

- list of “job killer” bills: http://www.calchamber.com/GovernmentRelations/Pages/Job-Killers-2013.aspx

- states on its website: http://www.calchamber.com/headlines/pages/04262013-taxcreditsunsetbillmovestoassembly.aspx

- Franchise Tax Board’s: https://www.ftb.ca.gov/index.shtml?disabled=true

- 2011 Tax Expenditure Report: https://www.ftb.ca.gov/aboutftb/Tax_Expenditure_Report_2011.pdf

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2013/08/27/sb-365-aims-at-limiting-tax-credits/