Hey Sacramento — publicly-funded arenas are bad for business

by Katy Grimes | October 28, 2013 9:05 am

While running record deficits, Sacramento’s Mayor Kevin Johnson and city officials approved a $447.7 million arena deal at the Downtown Plaza[1] in March, claiming a public-private partnership – only the private contributions amount to about one-third. [2]

[2]

Sacramento’s publicly funded arena deal has been billed as “the largest redevelopment project in city history” in Sacramento, which should make every tax payer shudder.

A publicly funded arena will mean Sacramento taxpayers can expect a giant toilet flushing publicly funding. Other people’s money is so easy to recklessly spend.

City-created the blight

The blighted Downtown Plaza in downtown Sacramento is entirely the fault of the city, through eminent domain, and its lousy property management. As the largest slumlord on the street, the city is responsible for driving the downtown K Street Mall area from a once-bustling pedestrian mall filled with independently owned shops and department stores, into a crime laden, blighted area replete with abandoned buildings and homeless people — after spending hundreds of millions of dollars in redevelopment money on the space.

Sacramento Police Department has had to cut cops. There are no road repairs. Park maintenance is dwindling. City services overall have been cut already. The publicly funded arena will just usher in massive debt. And when the team can no longer pay its bills, the city, already sinking under huge debt and unfunded pension liability, will file for bankruptcy.

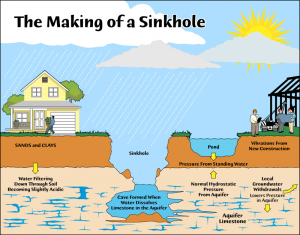

Publicly funded arena deals are public sinkholes, and a bad deal for taxpayers.

New York arena bust

The Wall Street Journal just reported [3]the New York City Barclays Center[4] arena is not producing nearly the revenue projected. The Barclays Center is not only losing money, it made only one-third the first year projected revenue, and can’t pay the annual debt service.

Sacramento’s bad deal

Officials claim the Sacramento arena deal would require the city to commit “$258 million in value, or 58 percent of the arena cost,” according[5] to reports in the Sacramento Bee. “Of that, $212 million would come from selling bonds backed by future revenues from city downtown parking garages. The city’s contribution is the same as it was in last year’s aborted project to build an arena at the downtown railyard.[6]”

But that’s just part of the public’s contribution. Public policy watchdog Eye on Sacramento[7], says the public’s contribution is actually $375 million, when all of the publicly owned assets being thrown into the deal are accounted for.

What else is being thrown into the pot? The city also agreed to give the arena private development group the city’s empty 100-acre plot next to Sleep Train Arena in North Natomas,[8] as well as six other city properties, five of them adjacent to or near the downtown arena site.

And Sacramento officials are giving away the city’s parking lot and metered parking revenue, after claiming the parking lots have no value.

Is it any wonder economists think arenas make bad investments for taxpayers?

Arenas and sports stadiums a bust

“The basic idea is that sports stadiums typically aren’t a good tool for economic development,” said Victor Matheson,[9] an economist at Holy Cross who has studied the economic impact of stadium construction for decades, reported the Atlantic[10]. “When cities cite studies (often produced by parties with an interest in building the stadium) touting the impact of such projects, there is a simple rule for determining the actual return on investment, Matheson said: ‘Take whatever number the sports promoter says, take it and move the decimal one place to the left. Divide it by ten, and that’s a pretty good estimate of the actual economic impact.’”

“The main problem, I think, with the public financing of sports stadiums isn’t that they happen, but that they happen so often because of how they are sold to taxpayers.”

[11]

[11]

Ohio arena bust

“Nearly 20 years after county officials promised that public financing for a pair of professional sports stadiums would help usher in a new era of economic vitality, the reality is somewhat different,” the Huffington Post reported in March about Drake Center. “The county’s agreement to build new stadium facilities for the Cincinnati Bengals and the Cincinnati Reds has been described as ‘one of the worst professional sports deals ever struck by a local government[12]’ by the Wall Street Journal.”

Arizona arena bust

In June 2012, the city council of Glendale, Arizona, decided to spend $324 million on the Phoenix Coyotes, an ice hockey team that plays in Glendale’s Jobing.com Arena.

“As the city voted to give a future Coyotes owner hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars, it laid off 49 public workers, and even considered putting its city hall and police station up as collateral to obtain a loan, according to the Arizona Republic,” the Atlantic reported[13]. “The latter plan was ultimately scrapped.”

Glendale is on the hook for $15 million per year over 20 years to a potential Coyotes owner, but also committed to $12 million annual debt payment for construction of its arena. In return, the city receives only $2.2 million in annual rent payments, ticket surcharges, sales taxes and other fees.” The city will still lose $9 million annually.

The art of the deal

The pubic cost of Sacramento’s current arena subsidy plan will require payments of $25 million per year for 27 years after the initial 8 years of “interest only” payments. The state recently prohibited school districts from using similar long-term “capital appreciation” bonds.

Arena projects rarely make economic sense because of the flawed way they are structured. Stadiums and arenas are financed with long-term bonds, sticking cities with the debt for unusually long periods of time. Sacramento’s arena bond debt will be around for at least 30 years.

- Downtown Plaza: http://sacdowntownplaza.com

- [Image]: http://calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/724-730-K-street.jpg

- just reported : http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304384104579143503249017682

- Barclays Center: http://atlanticyardsreport.blogspot.com/2013/10/barclays-center-more-prominent-than.html

- according: http://www.sacbee.com/2013/03/24/5288161/448-million-arena-deal-reached.html

- railyard.: http://topics.sacbee.com/railyard/

- Eye on Sacramento: http://eyeonsacramento.com/2013/03/an-eye-on-sacramento-report-on-the-arena-proposal/

- ,: http://topics.sacbee.com/North+Natomas/

- said Victor Matheson,: http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/if-you-build-it-they-might-not-come-the-risky-economics-of-sports-stadiums/260900/

- the Atlantic: http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/if-you-build-it-they-might-not-come-the-risky-economics-of-sports-stadiums/260900/

- [Image]: http://calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/SinkholePoster.png

- one of the worst professional sports deals ever struck by a local government: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704461304576216330349497852.html

- reported: http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/if-you-build-it-they-might-not-come-the-risky-economics-of-sports-stadiums/260900/

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2013/10/28/hey-sacramento-publicly-funded-arenas-are-bad-for-business/