Gov. Brown, Legislature push groundwater regulation

by Wayne Lusvardi | March 14, 2014 4:53 pm

This is Part 1 of a two-part series.

[1]Due to the current compound drought and water storage shortage, California legislators are considering enacting groundwater regulation over the entire Central Valley aquifer. Some recent developments:

[1]Due to the current compound drought and water storage shortage, California legislators are considering enacting groundwater regulation over the entire Central Valley aquifer. Some recent developments:

- State Sen. Fran Pavley, D-Agoura Hills, chairperson of the Water Committee of the California Senate, is considering legislation to do so. Pavley has been floating bills to regulate groundwater since 2009[2].

- Water expert Peter Gleick[3] has been saying for some time that there is a looming groundwater catastrophe in California.

- In his 2014 State of the State Address, Gov. Jerry Brown called for “serious groundwater management”[4] to crack down on overdrafting.

- The California Legislative Analyst Office on March 11 released a new study, “Improving Management of the State’s Groundwater Resources.”[5] It reported the governor’s budget proposal for fiscal year 2014-15, which begins on July 1, includes $1.9 million for 10 positions to establish a new groundwater policing and regulatory bureaucracy that would begin superseding longstanding state groundwater and property rights laws.

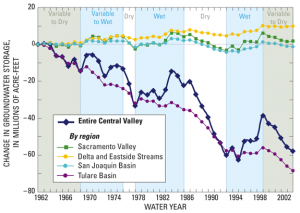

However, as of 2000, the aquifer had 390 years of remaining water storage left and is depleting at a rate of only 0.25 percent per year, according to a 2012 study conducted under the sponsorship of the National Academy of Sciences[6]. Additionally, the study concluded that nearly the entire threat of depletion is isolated in the Tulare Basin.

The study was headed by researcher Bridgett R. Scanlon[7], of the Jackson School of Geosciences at the University of Texas, Austin. The title of the study: “Groundwater Depletion and Sustainability of Irrigation in the U.S. High Plains and Central Valley.”[8]

According to the California Department of Water Resources Groundwater Bulletin No. 118[9] in 2003, California depends on groundwater to meet about 30 percent of its needs in average years, about 60 percent in wet years.

Adjudicated groundwater

Currently, the California government effectively does not regulate groundwater, leaving regulation to a longstanding adjudication process in state courts. Such adjudicated groundwater basins are examples of self-regulated groundwater management[10], with the courts acting only as referees. It is unnecessary to regulate or adjudicate many agricultural water basins because farmers have agreed not to draw down underground water levels below a certain pre-agreed depth to avoid depletion that would ruin their farms.

If groundwater basins are not drawn down below their annual safe yield[11], they will recharge. If they are lowered below the safe yield, they will deplete. According to Scanlon’s study, California’s Central Valley aquifer is depleting, but at a very slow rate. However, the unintended consequences of diversions of water for fish under pressure from environmental lobbies are resulting in a secondary groundwater depletion crisis.

Scanlon’s study and the State Department of Water Resources estimate the annual overdraft is about 1 million acre-feet of water per year. However, the primary source of recharge of water basins (60 percent) is agricultural irrigation[12].

But in recent years, the greater percentages of system water being flushed through rivers to the ocean for fish runs means the newest source of groundwater depletion is environmental diversions of water. In 2012 alone, 800,000 acre-feet[13] of Central Valley water was flushed to the sea for fish runs. In 2013, upstream from the Central Valley, 453,000 acre-feet of water[14] was diverted from Trinity Lake for fish flows.

If Brown’s new state regulatory program is instituted, ironically farmers would end up being policed for overdrafting, when actually they are the primary source of recharging basins.

Media misunderstanding of how groundwater works also often portrays farmers as criminals. The Modesto Bee recently reported that the expansion of almond orchards totaling 4 million trees in Stanislaus County would consume enough water for 480,000 people[15]. That would be enough water for the entire City of Fresno for one year.

But the groundwater in Eastern Stanislaus County is not available to be put into the San Joaquin River for statewide municipal use or for fish runs. Moreover, the California Area of Origin Law[16] would prohibit grabbing water in Stanislaus County for use elsewhere. And shifting orchards to where groundwater is abundant liberates water in the State and Federal water systems for cities and fish.

Groundwater managed, not regulated

Up to now, groundwater has not been regulated, but managed in California. After the passage of Assembly Bill 3030 in 1992[17] (Water Code Section 10750 et seq.), local agencies were authorized to manage groundwater. More than 200 agencies adopted groundwater management plans.

The major difference between voluntary local government groundwater management and state regulation is that the state has the power to issue shut-down notices and compel compliance with law enforcement. A local groundwater management agency is able to monitor wells and issue surcharges on pumping too much water, but it can’t stop a landowner with water rights from pumping water.

And there still are some areas of the state that have not adopted such management plans. Liability issues, the high cost of adjudicating water basins, the ability of farmers to self-manage groundwater levels, the complexities of existing water rights, and the lack of legal conflicts over local groundwater usage have made groundwater regulation unnecessary in many areas. Groundwater is not generally monitored in some 200 water basins[18] where the population is sparse and groundwater withdrawals are typically low.

The DWR reports that groundwater is already monitored in 10,000 active water wells where the water is mostly used.

DWR recently implemented a new groundwater surveillance mechanism, the California Statewide Groundwater Elevation Monitoring in 2012, in accordance with State Senate Bill SB-X7-6 of 2009[19]. This report is provided every 5 years to the legislature.

(In Part 2 of this series, the hydrological flaws and consequences of a potential new green groundwater regulatory plan will be discussed.)

- [Image]: http://calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Water-chart.png

- 2009: http://sd27.senate.ca.gov/news/2009-10-25-pavley-s-groundwater-monitoring-bill-added-water-package

- Peter Gleick: http://blog.sfgate.com/gleick/2009/07/14/californias-looming-groundwater-catastrophe/

- “serious groundwater management”: http://gov.ca.gov/news.php?id=18373

- Improving Management of the State’s Groundwater Resources.”: http://www.lao.ca.gov/handouts/resources/2014/Groundwater-Resources-03-11-14.pdf

- a 2012 study conducted under the sponsorship of the National Academy of Sciences: http://www.pnas.org/content/109/24/9320.full

- Bridgett R. Scanlon: http://www.beg.utexas.edu/personnel_ext.php?id=70

- “Groundwater Depletion and Sustainability of Irrigation in the U.S. High Plains and Central Valley.”: http://www.pnas.org/content/109/24/9320.short

- California Department of Water Resources Groundwater Bulletin No. 118: http://www.water.ca.gov/pubs/groundwater/bulletin_118/california's_groundwater__bulletin_118_-_update_2003_/bulletin118_entire.pdf

- adjudicated groundwater basins are examples of self-regulated groundwater management: http://www.amazon.com/Dividing-Waters-William-A-Blomquist/dp/1558152105

- safe yield: http://www.aquapedia.com/safe-yield/

- primary source of recharge of water basins (60 percent) is agricultural irrigation:

- 800,000 acre-feet: http://calwatchdog.com/2014/02/06/drought-wars-where-did-the-farm-water-go/

- 453,000 acre-feet of water: http://calwatchdog.com/2014/02/06/drought-wars-where-did-the-farm-water-go/

- almond orchards totaling 4 million trees in Stanislaus County would consume enough water for 480,000 people: http://www.modbee.com/2014/03/01/3217103/new-eastside-stanislaus-county.html

- Area of Origin Law: http://www.c-win.org/area-origin-statutes.html

- Assembly Bill 3030 in 1992: http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/gwmanagement/ab_3030.cfm

- not generally monitored in some 200 water basins: http://www.water.ca.gov/pubs/groundwater/bulletin_118/california's_groundwater__bulletin_118_-_update_2003_/bulletin118_entire.pdf

- California Statewide Groundwater Elevation Monitoring in 2012, in accordance with State Senate Bill SB-X7-6 of 2009: http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/casgem/

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2014/03/14/gov-brown-legislature-push-groundwater-regulation/