Cal Lutheran: State growth anemic next 2 years

by John Seiler | March 15, 2014 1:56 am

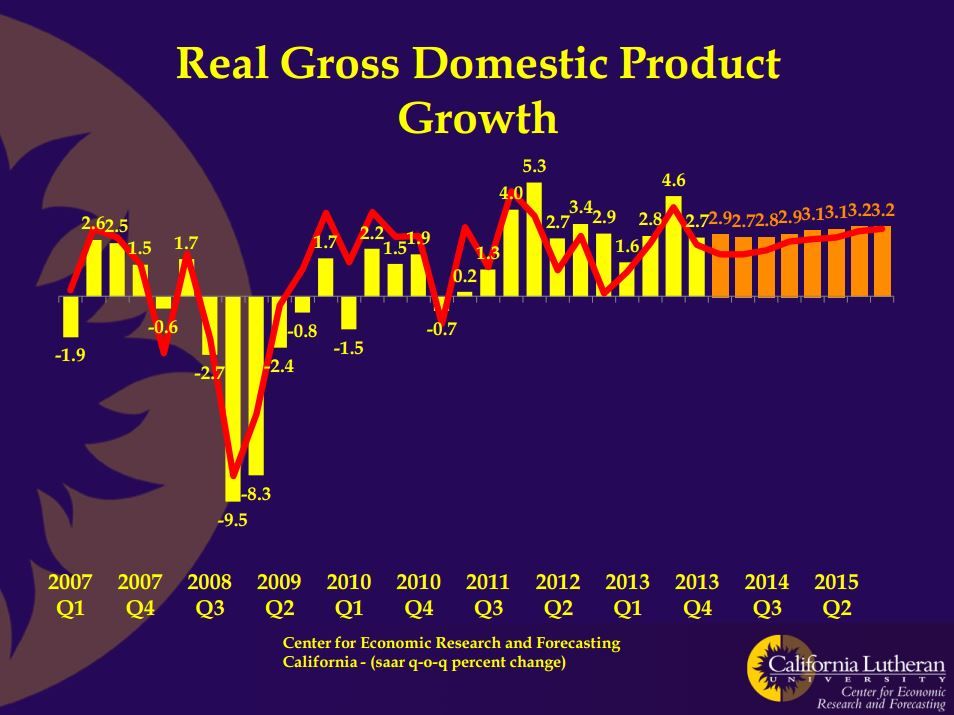

California’s economic recovery remains anemic and a two-year projection put forth in the March forecast of the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting[1] at Cal Lutheran predicts more of the same. Here’s the chart:

[2]

[2]

Notice that growth the next two years will average only about 3 percent, when at least 4 percent is needed to begin making up for the huge losses during the Great Recession. At that time, as the chart showed, the economy was in free fall with “growth” declining at nearly a 10 percent annual rate.

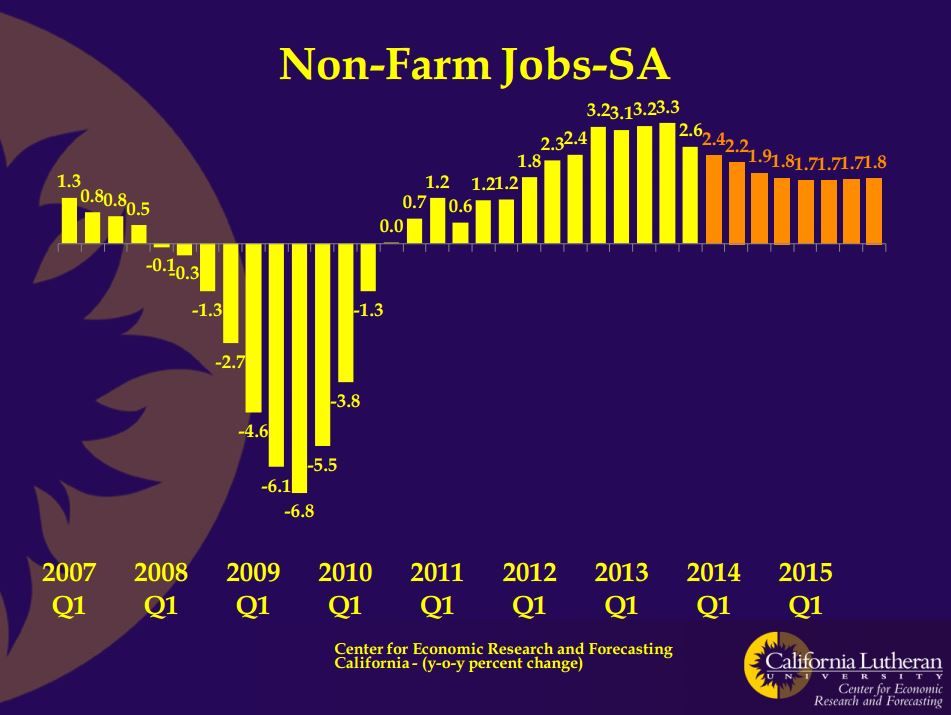

CERF also expects jobs growth to be weak, at under 2 percent the next couple of years, as the following chart shows. Again, that remains anemic, and isn’t enough to make up for the massive jobs crash during the Great Recession. Notice the 6.8 annual rate of jobs destruction on the chart.

[3]

[3]

According to CERF Director Bill Watkins:

I think this is unsatisfactory, because the growth is too slow to help the most disadvantaged among us. It’s also unsatisfactory because government policy is a reason that our economy is growing so slowly. …

California, though, has created a set of policies that couldn’t be more effective in constraining

economic growth if constraining growth was the purpose of policy. I describe this policy set as

DURT: Delay, Uncertainty, Regulation and Taxes.

The CERF analysis jibes with last November’s finding[4] by the U.S. Census Department that California, when the cost of living is taken into account, has the highest poverty rate of any state.

DURT

Watkins explained the meaning of DURT:

“D” stands for Delay. It means the difficulty of starting projects because of the immense amount of red tape imposed by the state. He said:

A building can be planned, built and completed in Texas, while a similar project is still in the early stages of planning in California. Heck, the Transcontinental Railroad was built in less time than a railroad station would be approved in California today. In California, a project requires the approval of “stakeholders,” apparently defined as anyone who objects to the project. If a “stakeholder” objects and the developer tries to move forward, the project’s cost can be driven up without limit by endless environmental lawsuits.

“U” stands for Uncertainty. Businesses have no idea what regulations will grind into them in the future, nor what existing regulations even mean. Watkins:

California cities’ code and planning documents mean little or nothing. In many cities, if a project is submitted and it meets every condition of building codes and planning documents, that’s just the beginning of negotiations.

“R” stands for Regulation. In particular, said Watkins, the state’s economy is being strangulated by carbon regulations, such as AB32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006[5]. He brought up a great irony:

There is nothing local about carbon dioxide. It is a gas that spreads itself throughout the

environment. However, in part because of mindless repeating of the phrase “Think

globally, act locally” California’s approach to atmospheric carbon reduction is perverse.

California has one of the most carbon efficient economies on earth. That is we use

relatively small amounts of carbon to generate a unit of economic activity. Reducing

carbon emissions here is expensive. By contrast, China is very carbon inefficient. A

dollar spent reducing carbon there would achieve far more than a dollar spent trying to

reduce emissions here.

“T” stands for Taxes. And California has the highest income, sales and gas taxes in the country. Watkins warned:

California’s highest-in-the-nation top marginal tax rate is layered atop other DURT components and thus is even more detrimental than it otherwise would be. If it were up to me, I’d fix the delay, uncertainty, and regulation issues and see where we are then. My guess is that the increased economic activity would be enough to allow cuts in top marginal taxes while increasing government spending, making the state even more attractive.

Unfortunately, he said, reform is going to be difficult because “powerful forces are heavily invested in the status quo.”

State budget

Watkins noted that the state’s seemingly good state budget numbers, producing surpluses instead of deficits, reflect the inrush of taxes from the Proposition 30 tax increase, passed by voters in 2012; and from the recent increases in stock market valuations.

He also commended Gov. Jerry Brown for not going on a spending binge, as Gov. Gray Davis did in 1999-2000 during the dot-com boom of that time; which resulted in the $40 billion deficits of 2001-02, as the dot-com boom turned into a dot-bust.

On new spending projects, Watkins dings Brown for only two things: First, the governor’s pet project, high-speed rail.

Second, “not addressing California’s other financial issues, the ones that are contributing to California’s dismal credit rating.” These include what Brown himself has dubbed the “Wall of Debt” the state owes, such as $4.5 billion a year[6] to the California State Teachers Retirement System to keep it solvent.

Otherwise, Watkins said, Brown “effectively resisted the legislature’s knee-jerk impulse to increase long-term spending commitments.”

In short, the state shows some improvements that certainly are better than the decline during the Great Recession. But California’s economy just isn’t strong enough to propel growth to lift many people out of poverty, and to maintain a strong middle class.

- Center for Economic Research and Forecasting: http://www.clucerf.org/

- [Image]: http://calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Cerf-real-domestic-product-growth.jpg

- [Image]: http://calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/CERF-Non-Farm-Jobs-SA.jpg

- last November’s finding: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/11/07/california-highest-rate-of-poverty_n_4233292.html

- AB32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006: http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/ab32/ab32.htm

- $4.5 billion a year: http://calpensions.com/2013/04/15/calstrs-benefit-hikes-big-part-of-pension-debt/

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2014/03/15/cal-lutheran-state-growth-anemic-next-2-years/