What groundwater regulation will bring

by Wayne Lusvardi | March 17, 2014 1:59 pm

This is Part 2 of a two-part series. Part 1 is here[1], and described California’s new green groundwater regulatory scheme. For the first time, California is not only going to manage groundwater basins, but conduct surveillance and policing of groundwater withdrawals.

[2]

[2]

California’s Central Valley groundwater is mainly found in four large subregional basins[3]: the Sacramento Basin, the Delta and Eastside Streams, the the San Joaquin Basin and the Tulare Basin. According to the U.S. Geological Survey[4], the San Joaquin Basin has recovered from depletion after the State Water Project brought water to farms in the area in the 1970s. But the Tulare Basin still is showing signs of decline.

However, a study by Bridgett R. Scanlon[5] indicates that “water banking” in the Tulare Basin mostly in Kern County has significantly offset losses. She is a researcher at the Jackson School of Geosciences at the University of Texas, Austin.

In he 1995 book, “Water Banks: Untangling the Gordian Knot of Western Water,”[6] Lawrence J. MacDonnell explained:

“Water banking in its most generalized sense is an institutionalized process specifically designed to facilitate the transfer of developed water to new uses. Broadly speaking, a water bank is an intermediary. Like a broker, it seeks to bring together buyers and sellers. Unlike a broker, however, it is an institutionalized process with known procedures and with some kind of public sanction for its activities.”

The Kern County Water Bank Authority[7] manages its 32-square mile water bank in the Tulare Basin. The Water Bank is a giant water recycling system. The bank has 7,000 acres of recharge ponds and can recharge from 30,000 to 72,000 acre-feet of water per month. The Kern County Water Bank can hold 10 million acre-feet of water. The accessible storage is 1.5 million acre-feet.

The bank mainly recycles imported water from the state and federal water systems for recharge. The recovery rate is about 240,000 acre-feet in a year. Thus, the Bank has about six years of accessible storage.

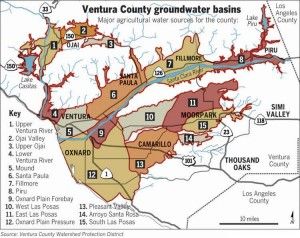

Green water diversions have created crisis in Ventura County

[8]In 1979, seawater began intruding into freshwater aquifers in the Oxnard Plain in Ventura County. State officials threatened to seek a court order limiting groundwater pumping for the first time in California history. But the Ventura County Board of Supervisors and the Fox Canyon Groundwater Management Agency ignored the regulators and instead financed a $31 million diversion dam to retard seawater intrusion and the problem was solved.

[8]In 1979, seawater began intruding into freshwater aquifers in the Oxnard Plain in Ventura County. State officials threatened to seek a court order limiting groundwater pumping for the first time in California history. But the Ventura County Board of Supervisors and the Fox Canyon Groundwater Management Agency ignored the regulators and instead financed a $31 million diversion dam to retard seawater intrusion and the problem was solved.

The crisis resurfaced in 2014[9] with the combination of drought and federal orders to retain more water in the Santa Clara River for Steelhead Trout. More water is now being pumped than is sustainable. This has resulted in less freshwater to hold back the seawater in local groundwater basins. But groundwater pumping has actually decreased from the 1980s from 160,000 acre-feet of water to 125,000 acre-feet. The sustainable level is thought to be 100,000 acre-feet.

The Safe Yield to pump water set decades ago no longer works when water for fish has to be allowed to flow to the sea instead of into water basins. The problem becomes even more noticeable when drought compounds the problem. The groundwater crisis in the Oxnard Plain has been called by WaterWorld.com[10] an “existential crisis” to Ventura’s agricultural industry.

The Fox Canyon Groundwater Management Agency has been proactive in self-management of the water basin. It has required well monitoring, limited construction of new wells and reduced pumping. And it imposed surcharges on pumpers not meeting reduction targets. But water is viewed as a property right.

Solutions such as building a water desalting plant and using recycled water are being explored. But the problem is the cost of water. Green diversions of water from farmers for fish are causing farming to become economically unsustainable in a globalized world where cheap crops can be imported from Mexico and Chile.

For decades, Ventura farmers have resisted setting up an adjudicated water basin, meaning the longstanding state court system [11]and procedures would decide matters. But they may choose adjudication over regulation by the state. Adjudication typically comes when one agricultural pumper against another files a lawsuit.

Regulating and stigmatizing the “Overdrafters”

There is a long-term groundwater crisis in the Central Valley, mainly in the Tulare Basin, where water banks have been established to counter the problem. Groundwater is already managed and monitored where most of the groundwater is extensively pumped.

The long-term crisis is the depletion of the aquifer. But the problem is occurring so slowly that it is not an imminent crisis. The major solutions being discussed to this long crisis are water banking and adding new water reservoirs.

Some other solutions being discussed — such as cleaning up nitrates, perchlorate or other contaminants — would do nothing to recharge the Tulare Basin because that water is already underground. The immediate crisis of small rural towns having no water supply by summer is more difficult[12] and probably too late to fix permanently this year, except by trucking water in. Cleaning up subsurface toxic water would help small towns, but the cost might be prohibitive.

New regulations

The new groundwater regulation apparatus that Gov. Jerry Brown and the Legislature are erecting may end up criminalizing farmers for water overdrafting, even though the problem actually originates in the diversions of water for fish runs. As the Legislative Analyst’s March 11 report[13] on groundwater admits, there is a physical connection between groundwater and surface water.

But the state’s new groundwater laws are based on a flawed depletion hydrology model that doesn’t recognize that farmers are also a source of significant recharge of water basins not solely scofflaw “overdrafters.” But as was described in Part 1[14] of this series, farmers are also the “rechargers.”

It is going to be interesting to see if the state’s new groundwater regulatory bureaucracy is going to end up limiting the withdrawals of groundwater by farmers that will only result in the greater depletion of groundwater basins for lack of recharge. And how will regulators measure whether the overdraft came from farming or environmental diversions when it is often all the same water?

- here: http://calwatchdog.com/2014/03/14/gov-brown-legislature-push-groundwater-regulation/

- [Image]: http://calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/California-regions.png

- four large subregional basins: http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2009/3057/

- U.S. Geological Survey: http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2009/3057/

- a study by Bridgett R. Scanlon: http://www.pnas.org/content/109/24/9320.short

- “Water Banks: Untangling the Gordian Knot of Western Water,”: http://www.ecy.wa.gov/programs/wr/instream-flows/wtrbank.html

- Kern County Water Bank Authority: http://www.kwb.org/index.cfm/fuseaction/Pages.Page/id/352

- [Image]: http://calwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Ventural-county-groundwater.jpg

- resurfaced in 2014: http://www.waterworld.com/news/2014/02/21/a-groundwater-crisis-has-resurfaced-in-ventura-county.html

- called by WaterWorld.com: http://www.waterworld.com/news/2014/02/21/a-groundwater-crisis-has-resurfaced-in-ventura-county.html

- the longstanding state court system : http://www.water.ca.gov/pubs/groundwater/adjudicated_ground_water_basins_in_california__water_facts_3_/water_fact_3_7.11.pdf

- difficult: http://www.fresnobee.com/2011/10/03/2559549/solutions-to-drinking-water-crisis.html

- Legislative Analyst’s March 11 report: http://www.lao.ca.gov/handouts/resources/2014/Groundwater-Resources-03-11-14.pdf

- Part 1: http://calwatchdog.com/2014/03/14/gov-brown-legislature-push-groundwater-regulation/

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2014/03/17/what-groundwater-regulation-will-bring/