Uber mobilizes support against Sacramento regulations

by James Poulos | August 11, 2014 5:34 pm

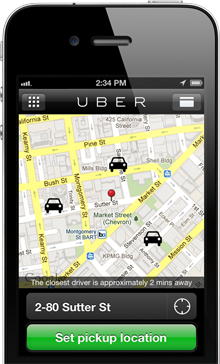

In a fight, you go with your strengths. Uber[1] is the social media site whose app connects drivers with riders. Taxis drivers and others don’t like it, and are trying to enact legislation to limit it.

Uber now has responded by using the power of social networking to save its business model and fight two bills in the California Legislature.

The more straightforward of the two bills is Assembly Bill 612[2], by Assemblyman Adrin Nazarian, D-Sherman Oaks. Fueled by the support of taxi drivers, who have long been required by law to submit to detailed government licensing requirements, Nazarian’s bill would extend similar regulations to Uber drivers. In addition to public permitting, drivers would have to accept background tests, drug tests and fingerprinting.

As supporters of AB612 went on the record, their hostility toward Uber quickly became evident. According to the Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles city councilman Paul Koretz described[3] Uber, Lyft and other firms as “well-financed bandit cabs with apps.”

As a result of the double attack, Uber has taken to the court of public opinion, urging users and allies of the service to pressure California state legislators to vote down the bills. In a statement posted[4] on the company’s blog, Uber took aim at both bills.

AB612, the company said, was “a flagrant attempt to stymie innovation and competition by an antiquated industry,” and “an obvious play by the taxicab industry to kill competition and limit consumer choice.”

Insurance regulation

Meanwhile, a more complex piece of legislation made advance. AB2293[5] is by Assemblywoman Susan Bonilla, D-Concord. The primary aim is to draw Uber into the regulatory framework established by insurance law.

AB2293 was described as “a back-room deal by insurance companies and trial attorneys to prematurely force the ridesharing industry to fit their special interests.” It allowed insurance companies, Uber said, “to escape their liability for services they’ve already charged ratepayers,” while helping “trial attorneys work the system to ensure they get the largest payouts possible.”

Specifically targeting state senators sitting on the California Senate Energy, Utilities and Communications Committee, Uber pointed readers toward recent regulations in Colorado that avoided the pitfalls of AB612 and AB2293.

In Colorado, SB125, supported by Uber, created a new class of vehicles, “Transportation Network Companies.” Regulations crafted for that class required three things: a multi-state background check including driving records and felony offenses; a quality and safety inspection conducted by certified mechanic; and insurance on every ride, up to $1 million, “from the moment a driver accepts a ride request.”

That final provision was key to resolving the kind of disagreement that has riven California, for reasons that require some background to explain.

A complex controversy

AB2293 was designed to force Uber to abandon its preferred system of insurance coverage. Uber had grown accustomed to dealing with insurance in a somewhat improvised way. When passengers were inside Uber cars, Uber itself supplied so-called “primary” insurance coverage.

According to that system, in the event of an accident, Uber’s coverage was tapped first to cover damages, injuries and repairs. When passengers weren’t in the cars, however, each Uber driver’s personal auto insurance — not Uber’s insurance — became the primary coverage.

That meant, for instance, that if a driver with no passengers hit a pedestrian or crashed into a parked car, that driver would be personally liable through his or her auto insurance policy. Uber would be off the hook completely — with one exception. Uber supplies “contingent liability coverage” if a claim is denied by an insurance company on a driver’s personal coverage, which is primary during the time a driver is available but not carrying a passenger.

For critics, that arrangement seemed like something of a scam. It allowed Uber to cash in on the benefits of its service, while shifting the risks of its business model — like drivers unregulated by law — onto local residents.

Response

The response of Uber and its supporters was simple. Uber, they said, was providing a voluntary, in-demand service that delivers primary insurance when drivers are actually doing the job they were contracted to do. What’s more, Uber wasn’t leaving anyone in the lurch, because drivers freely contracted with Uber to cover off-the-job accidents through their own personal auto insurance.

There was just one catch. A reasonable person could say that Uber drivers weren’t always off the job if they didn’t have passengers in their vehicles. In fact, because Uber operates via a smartphone app, drivers must use their phones to access and interact with the app in order to acquire passengers and communicate with them pre-ride. During those times, drivers are effectively on-duty. And even though they’re not carrying passengers, they are using their smartphones while in the car — possibly while driving.

That’s the circumstance that could open pedestrians and other drivers up to liability that could reasonably be expected to be Uber’s responsibility. Colorado’s state Legislature addressed that situation by requiring insurance from the moment a ride request is accepted — not from the moment a passenger enters a Uber vehicle.

California’s competing bills, however, were not designed to target the legal gray area with as much precision as Colorado’s bill. What’s more, the special interests aligned against Uber in California have done an effective job of poisoning the well by taking such a hostile view of the company (and similar firms).

With no legislative alternative on the horizon for now, a battle in Sacramento has quickly begun to brew.

We’ll soon see whether California, which basically created social media at Facebook, Twitter and other companies including San Francisco-based Uber, itself severely hampers its most glittering and profitable industry. If Uber is harmed, what social media company next would come under fire in its home state?

Correction: The following wording was added after the word “completely”: “with one exception. Uber supplies ‘contingent liability coverage’ if a claim is denied by an insurance company on a driver’s personal coverage, which is primary during the time a driver is available but not carrying a passenger.”

We regret the error.

Also, an objection was made that Uber, Lyft and similar companies are not “social media.” In fact, they are, and not just because Uber is located in San Francisco. According to Oxford Dictionaries[6], social media are: “Websites and applications that enable users to create and share content or to participate in social networking.” In March, Shoutlet ran an article[7], “10 Lessons for Brands from Uber’s Social Marketing.” Bloomberg reported June 10[8], “Uber Rides Social Media Dominance to $17B Valuation.”

- Uber: https://www.uber.com/

- Assembly Bill 612: http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140AB612

- described: http://www.latimes.com/local/cityhall/la-me-0611-rideshare-fight-20140611-story.html

- posted: http://blog.uber.com/getonboard

- AB2293: http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/13-14/bill/asm/ab_2251-2300/ab_2293_bill_20140328_amended_asm_v98.html

- Oxford Dictionaries: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/social-media

- an article: http://www.shoutlet.com/blog/2014/03/10-lessons-brands-ubers-social-marketi/

- reported June 10: http://www.bloomberg.com/video/uber-rides-social-media-dominance-to-17b-valuation-KEbANwrZSXWccFk45A5OZQ.html

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2014/08/11/uber-mobilizes-support-against-sacramento-regulations/