State facing flood protection shortfall

by Dave Roberts | January 22, 2015 1:42 pm

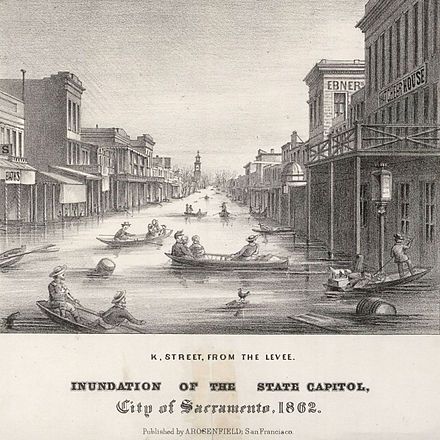

With California mired in the third year of drought, it might seem strange that an Assembly committee recently held a hearing[1] on flooding. That is, unless you’re one of the 6.6 million northern California residents who received a National Weather Service Flash Flood Warning[2] last month after weeks of steady and occasionally torrential rain. Kayakers were rowing[3] through central Healdsburg.

With California mired in the third year of drought, it might seem strange that an Assembly committee recently held a hearing[1] on flooding. That is, unless you’re one of the 6.6 million northern California residents who received a National Weather Service Flash Flood Warning[2] last month after weeks of steady and occasionally torrential rain. Kayakers were rowing[3] through central Healdsburg.

When California’s drought does eventually end, there’s a 33 percent to 40 percent chance it will be due to an “atmospheric river,” according to a 2013 study by the American Meteorological Society. The study is titled, “Atmospheric Rivers as Drought Busters on the U.S. West Coast[4].”

Specifically, the study found the “atmospheric river” has been “recognized as the cause of the large majority of major floods in rivers all along the U.S. West Coast and as the source of 30 percent – 50 percent of all precipitation in the same region.”

In the meantime, California is facing as much as a billion dollar annual funding shortfall for flood protection infrastructure, the Assembly Committee on Water, Parks and Wildlife[5] was warned Jan. 13.

“This past year with regard to the drought we’ve often heard the famous saying, ‘Never waste a good crisis,’” said committee Chair Marc Levine[6], D-San Rafael, in his opening remarks. “But we shouldn’t wait for crises to act. California has a long history of alternating between periods of drought and periods of flood. According to the California Department of Water Resources[7], over the last 60 years California has experienced more than 30 major flood events, resulting in more than 300 lives lost, more than 750 injuries and billions of dollars in disaster claims.

“The department states that one in five Californians, over 7 million of us, live in the 500-year flood plain. And that nearly $6 billion in assets, crops, structures and public infrastructure are exposed to flooding. With future development, population changes, climate change, the loss of major infrastructure, critical facilities and state commerce, that figure could climb much higher.”

Flood control

The good news is that Gov. Jerry Brown’s proposed budget[8] for fiscal year 2015-16, which begins on July 1, provides $1.1 billion for flood control projects. The bad news is this is the last of the money available from Proposition 1E[9], the $4.1 billion bond measure for flood protection passed in 2006 in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, which struck New Orleans and surrounding areas in Aug. 2005.

That leaves a significant funding shortfall, according to a March 2013 Public Policy Institute of California[10] study, “Paying for Water in California”[11]:

“Roughly 25 percent of the population lives in a floodplain in a state where climate change may bring warmer winters and more severe inland flooding, along with rising sea levels and storm surges on the coast. Much of the state’s flood-control infrastructure is aging, and rebuilding typically requires costly upgrades to meet higher safety standards. New capital investments of $800 million to $1 billion annually are needed to shore up the system. Statewide, this means doubling the amount of money currently spent by local residents on flood management.”

Ellen Hanak[12], a PPIC senior fellow and coauthor of that study, told the committee, “We are only a new storm away from big flood events, given the topography and our climate.” While much of the flooding potential is in the Central Valley, the state’s southern coastal areas and the Bay Area are also at risk, she said.

“Although we’re improving our flood infrastructure in a lot of places, the risk is growing because of a few other factors,” said Hanak. “One of them is just population growth, and the fact that we can’t completely eliminate the risk, especially behind levees. When more people and businesses locate in those places, it just increases the potential damage when we do have a flood.”

Global warming resulting in rising sea levels and more extreme weather are also contributing factors, she said.

Taxpayers liable

Although those living in the flood plains are most at risk, all California taxpayers are potentially on the hook to pay for flood damage, said Hanak. She cited the California Supreme Court’s Paterno ruling[13], which held the state liable for hundreds of millions of dollars in damages when a Yuba County levee failed in 1986, killing two people and damaging about 3,000 homes.

Although flood insurance would help spread the liability, fewer people have been purchasing it lately, said Hanak, “probably because it’s dry and the drought. Even in the 100-year flood plain, where folks really should have that insurance, it looks to us like maybe 22 percent of the people in that area have it right now.”

Perhaps most vulnerable is the Delta where a thousand miles of waterways are held back by levees, many of which are more than 100 years old.

“Currently only about 31 percent of the levees meet the minimum standard,” said Randy Fiorini, chairman of the Delta Stewardship Council[14]. “So we have a long ways to go. At the rate we are going, it’s going to take many, many years even to meet that standard.”

Hanak estimated the levee upgrade cost at $34 billion. “If you figure it reasonable to spend that in 25 years to address flood risk, then we should be spending $1.4 billion a year on investments, not counting maintenance,” she said. “We have been spending around $600 million annually. So we have to more than double that. The state will need to prioritize the bond funding because there’s not enough to go around for all of the needs.”

Drinking water

In the battle over limited tax dollars for the Delta, flood control often loses out, according to Melinda Terry, executive director of the California Central Valley Flood Control Association[15].

“We have a large population where there’s health and safety issues of having drinking water available to them,” she said. “So from a political sense, they are more powerful and they can beat that drum louder as it is really important to them. The population that’s protected by the flood system, our drum is much smaller and doesn’t beat as loudly and we don’t get as much of the attention.”

Preserving levees involves more than just throwing money at the problem. “One of the big issues, I’ll call it the elephant in the room that wasn’t brought up by any of the speakers, is vegetation on levees,” Terry said. “The Army Corps [of Engineers], as part of their periodic inspections, has a policy that you can’t have vegetation on the levees. For decades they weren’t enforcing that, so our levees have quite a bit. It’s very expensive to remove.”

The need to enforce levee regulations was seconded by Leslie Gallagher, acting executive officer of the Central Valley Flood Protection Board[16], which is in charge of 1,600 miles of levees.

“We have a 100-year old system that has been somewhat neglected that has lots of old things on and around it,” she said. “It’s very challenging. You have folks who have over the years grown accustomed to having levees in their backyard. There are beautiful rose gardens and play houses and structures on the levee. Convincing somebody that that doesn’t necessarily belong to them can be difficult. It is challenging.”

Property rights

Another challenge is figuring out exactly who has the rights to a particular piece of property. “Many of our property rights are from deeds that are very old, rolled up in bundles and starting to crumble,” said Gallagher. “They were never digitized, modernized or surveyed. It’s a barrier to enforcement if we don’t know what our property rights are.”

Levine summarized the hearing with two takeaways: “We’re not investing as much as we need to. As we spend down these bond dollars we’ll have an even large spending gap. You talked about the lack of enrollment in flood insurance and how this occurs during drought. Yet history informs us that flood follows drought. How can we start raising this as an issue? The drought came after a difficult economic period for our state, particularly those who live in those [Central Valley] areas. So there’s a little bit of a challenge for us on that.”

- hearing: http://calchannel.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=7&clip_id=2507

- Flash Flood Warning: http://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2014/12/11/emergency-alert-flash-flood-warning-dangerous-flooding-imminent-or-already-occurring-in-alameda-contra-costa-napa-sonoma-san-mateo-santa-clara-santa-cruz-counties/

- Kayakers were rowing: http://www.pressdemocrat.com/gallery/3237835-181/healdsburg-flooding

- Atmospheric Rivers as Drought Busters on the U.S. West Coast: http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/abs/10.1175/JHM-D-13-02.1

- Assembly Committee on Water, Parks and Wildlife: http://awpw.assembly.ca.gov/

- Marc Levine: http://asmdc.org/members/a10/

- California Department of Water Resources: http://www.water.ca.gov/

- budget: http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/2015-16/BudgetSummary/BSS/BSS.html

- Proposition 1E: http://www.water.ca.gov/irwm/grants/stormwaterflood.cfm

- Public Policy Institute of California: http://www.ppic.org/main/home.asp

- “Paying for Water in California”: http://www.ppic.org/main/pressrelease.asp?i=1464

- Ellen Hanak: http://www.ppic.org/main/bio.asp?i=72

- Paterno ruling: http://www.watereducation.org/aquapedia/state-liability-flood-protection-and-paterno-decision

- Delta Stewardship Council: http://deltacouncil.ca.gov/

- California Central Valley Flood Control Association: http://cvflood.org/

- Central Valley Flood Protection Board: http://www.cvfpb.ca.gov/

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2015/01/22/state-facing-flood-protection-shortfall/