3 new studies rap how school ‘reform’ law is working

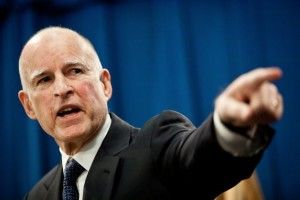

In 2013, after working with the Legislature for months on a comprehensive overhaul of California’s public school finances, Gov. Jerry Brown signed the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The governor called the law “historic” and hailed its dual goals: providing much more resources to directly help English-language learner students and foster children students, and providing more flexibility to local decision-makers on spending priorities.

In 2013, after working with the Legislature for months on a comprehensive overhaul of California’s public school finances, Gov. Jerry Brown signed the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The governor called the law “historic” and hailed its dual goals: providing much more resources to directly help English-language learner students and foster children students, and providing more flexibility to local decision-makers on spending priorities.

Under the law, each school district was supposed to adopt a Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP) to ensure English-learners and foster children were getting the extra help that Brown and lawmakers promised. These plans outline district priorities and relate them to funding decisions.

Three years later, California education reform groups increasingly question how the LCFF is working out. They cite little evidence of more resources going to struggling students and many instances of extra dollars going into general school district budgets, with the blessing of Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson.

This frustration led to the unusual decision last week of three reform groups — Public Advocates, Education Trust-West and Californians Together — to simultaneously issue studies that question how local LCAPs are being implemented.

Difficult to impossible to determine progress

EdSource has a roundup of their concerns:

Districts are not providing the level of transparency promised in exchange for increased spending flexibility,” wrote Public Advocates, a nonprofit law firm that has threatened to sue the West Contra Costa Unified School District for failing to disclose how it planned to spend millions of dollars on high-needs students. “Most districts are missing the opportunity to use the LCAP as a comprehensive planning tool for continuous improvement.”

“The usefulness of the LCAP as a means of accountability is compromised by the difficulty in gleaning a sense of coherence and what the plan actually entails,” Californians Together, a coalition of parent, professional and civil rights organizations focused on the needs of English language learners, wrote in a report, published this month, analyzing LCAP plans to improve services for English learners.

The reports, which follow similar analyses last year, studied several dozen LCAPs for the current school year from large and small, urban and rural districts. Public Advocates’ report, released Wednesday, can be found here. Education Trust-West’s report is here.

All three reports made the same overall criticisms: that it is often difficult, if not impossible, to find out how much some districts are spending on high-needs students; to track the expenditures over time; and to find a justification or rationale for districts’ spending decisions.

Brown won’t second-guess local funding decisions

Part of the reason for the frustration of reform groups isn’t related to problems implementing the Local Control Funding Formula at the district level. It’s with Gov. Brown, whose appointees on the State Board of Education sided with Torlakson on the question of whether the funds could be used for teacher raises and other broad district expenses.

Part of the reason for the frustration of reform groups isn’t related to problems implementing the Local Control Funding Formula at the district level. It’s with Gov. Brown, whose appointees on the State Board of Education sided with Torlakson on the question of whether the funds could be used for teacher raises and other broad district expenses.

At the 2013 signing ceremony for LCFF, Brown depicted the law as reflecting a historic new commitment to helping English-language learners. But of late, Brown administration officials have emphasized the “local control” aspect of the law — not the promises that more direct help would be given to the 1.4 million students who struggle with English in state public schools.

In a January 2015 telephone interview with editorial writers after unveiling his proposed 2015-16 budget. the governor said he would look into complaints that funds were going to teacher raises, not English-language learners.

But a year later, his aides took a sharply different position. In a January telephone interview with editorial writers after the governor unveiled his proposed 2016-17 budget, state Finance Director Michael Cohen said LCFF was meant to empower officials at local districts to make their own decisions. If they considered teacher raises a priority, the Brown administration had no issues with that, Cohen said.

The reform groups will present their critical findings about the law’s implementation to the State Board of Education at a meeting in May. The board is expected to try to fine-tune LCAP rules to make them easier to comply with and complete.

State Board of Education President Michael Kirst acknowledged local concerns about how unwieldy the process had become as a February state Senate hearing. But that hearing didn’t focus on the larger question of whether the LCFF’s initial goal of directly helping English-language learners and foster children was actually driving decisions at the district level.

Chris Reed

Chris Reed is a regular contributor to Cal Watchdog. Reed is an editorial writer for U-T San Diego. Before joining the U-T in July 2005, he was the opinion-page columns editor and wrote the featured weekly Unspin column for The Orange County Register. Reed was on the national board of the Association of Opinion Page Editors from 2003-2005. From 2000 to 2005, Reed made more than 100 appearances as a featured news analyst on Los Angeles-area National Public Radio affiliate KPCC-FM. From 1990 to 1998, Reed was an editor, metro columnist and film critic at the Inland Valley Daily Bulletin in Ontario. Reed has a political science degree from the University of Hawaii (Hilo campus), where he edited the student newspaper, the Vulcan News, his senior year. He is on Twitter: @chrisreed99.

Related Articles

Will CA trust SF Bay Bridge re-opening?

After months of controversy over the 36 cracked bolts on the new eastern span of the San Francisco/Oakland Bay Bridge,

Good news: State Senate cuts staff 4%

The good news keeps washing into California like a tubular wave. Due to budget problems, the California Senate cut its

Former San Francisco DA taking on L.A. DA in battle over criminal justice reform

The Los Angeles County district attorney’s race is shaping up as the highest-profile 2020 local election in the nation with