CA property tax revenue surges despite Prop. 13

by Chris Reed | July 18, 2016 8:11 am

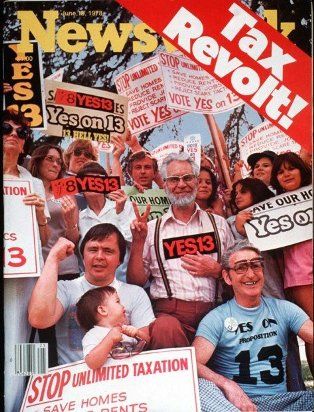

Proposition 13 — the 1978 ballot measure setting property taxes at 1 percent of assessed value and limiting annual increases in property taxes to 2 percent for homes and businesses which don’t change owners — is perhaps the most controversial of the limits put on state government through direct democracy.

Proposition 13 — the 1978 ballot measure setting property taxes at 1 percent of assessed value and limiting annual increases in property taxes to 2 percent for homes and businesses which don’t change owners — is perhaps the most controversial of the limits put on state government through direct democracy.

A ballot measure is likely in 2018 that aims to eliminate some or most of Prop. 13’s protections for commercial property — a concept known as “split roll” that has been discussed for decades. In May 2015, a coalition of unions set up a group called Make It Fair that originally talked[1] about launching a 2016 ballot measure before pulling back over concerns it could harm chances to pass a November 2016 ballot measure extending the “temporary” income taxes on the wealthy that voters approved in 2012.

Split roll advocates say property taxes should be a much more important part of paying for government in a sprawling state with many needs. They cite evidence[2] that economically successful mega-states Texas and Florida have much higher basic property tax rates.

Critics cite a 2012 Legislative Analyst’s Office report[3] that challenged the assumption that Prop. 13 had starved the state of revenue. “Since 1979, revenue from the 1 percent rate has exceeded growth in the state’s economy,” the LAO noted. Other studies have found that property tax revenue has gone up by higher percentages that income and sales tax over the same span.

Record annual revenue of $60 billion looms

Now there’s fresh evidence that despite limits on property tax increases, revenue growth in the tax category can be robust. Reports this month show that homes and businesses changing hands and having assessments go up along with new construction could mean annual property tax revenue will be $3 billion higher than expected by Gov. Jerry Brown’s Department of Finance; the state could receive a record $60 billion.

The Bay Area is leading this surge.

San Francisco City/County is 8.8 percent ahead of predictions; Santa Clara County is 7.9 percent ahead, San Mateo County is 7.6 percent ahead; Napa County is 7.1 percent ahead; and Alameda County is 7 percent ahead.

Gains are more modest in Southern California, paced by Los Angeles County and San Diego County each running 5.6 percent ahead of expectations and Orange County up 5.4 percent.

Nevertheless, these gains are unlikely to head off a 2018 split roll ballot battle. That’s partly because perhaps the most powerful critic of the idea — Gov. Brown — will be in the final months of his fourth and final term.

Last October, Brown raised eyebrows — and prompted rebukes — when he likened efforts to tinker with Prop. 13 to a “tar baby.”[4] The racially tinged term comes from 19th century folklore. Brown’s spokesman said his intent was plain: to suggest it was a bad idea and nothing more. At the same event, the governor also specifically opposed split roll.

‘Split roll’ likely focus of 2018 governor’s race

The topic is likely to be a factor in the governor’s race in 2018. Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom has been an intermittent critic[5] of Prop. 13 over the years. Last year, Treasurer John Chiang has said he would consider reforms but was cool[6] to split roll. Former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa has long backed[7] split roll.

Another signature-gathering campaign targeting Prop. 13 is possible in 2018 that takes a different approach. Southern California nonprofit groups that advocate for anti-poverty programs have proposed subjecting real estate properties assessed at more than $3 million to a 1 percent property tax surcharge.

It was formally floated[8] in 2015 before being dropped early this year because of concerns about other tax measures on the crowded November 2016 ballot. The proposal was initially forecast to raise nearly $8 billion a year.

- talked: http://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/politics-columns-blogs/dan-walters/article35133240.html

- evidence: http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-adv-welch-california-tax-reform-20140530-story.html

- report: http://www.lao.ca.gov/reports/2012/tax/property-tax-primer-112912.aspx

- “tar baby.”: http://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/capitol-alert/article38121273.html

- critic: http://www.foxandhoundsdaily.com/2009/03/mr-newsom-goes-santa-monica/#comments

- cool: http://calwatchdog.com/2015/03/02/treasurer-chiang-talks-taxes-and-the-economy/

- backed: http://www.dailynews.com/article/ZZ/20110816/NEWS/110819422

- floated: http://www.oag.ca.gov/system/files/initiatives/pdfs/15-0043%20%28Prenatal%20and%20Early%20Childhood%20Services%29_0.pdf?

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2016/07/18/ca-property-tax-revenue-surges-despite-prop-13/