Are voters ready to approve two massive tax hikes in 2020?

by Chris Reed | June 12, 2019 10:41 am

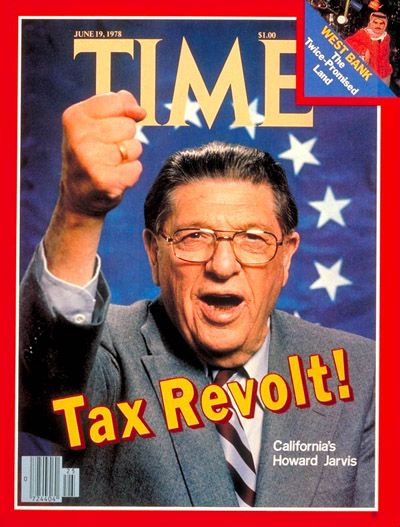

Because voters approved Proposition 13 [1]in 1978 — the ballot initiative that capped property tax hikes at 2 percent per year and required a two-thirds vote of the Legislature before taxes could be added or increased — California became known as the birthplace of the anti-tax movement that swept the nation. After President Ronald Reagan got a 25 percent income tax cut [2]through Congress in 1981, antipathy toward taxes became a defining feature of modern conservatism.

The Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, business groups and Republican activists enjoyed decades of success in fighting off tax hikes in the Legislature and on the ballot. And in 2010 — long after California’s emergence as a progressive redoubt — this potent partnership won voter approval of Proposition 26[3], which targeted local and state efforts to get around laws like Proposition 13 by defining taxes as “fees” which only need majority approval by legislative bodies. It eliminated this loophole and applied the two-thirds approval threshold for tax hikes to local governments.

But less than a decade later, anti-tax groups have the right to feel besieged in California. In 2012, voters approved Proposition 30[4], which increased sales taxes for four years and income taxes for those who made $250,000 or more by seven years. In 2016, voters approved Proposition 55[5], which extended the higher income taxes on the wealthy until 2030.

Teacher unions push for Prop. 13 ‘split roll’

And in November 2020, it appears increasingly likely that voters will be asked to consider two separate ballot measures that would each raise state taxes by about $11 billion.

One measure — the California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act — has already made the ballot. Sponsored by the League of Women Voters and pushed by teachers unions, it would create a “split roll” exception for commercial property from Proposition 13, allowing the parcels to immediately have sharply higher assessments based on their current value and exposing many businesses to the possibility of large annual property tax hikes in an era in which property values are soaring.

About $5.5 billion of the annual revenue would go to counties and cities for local services. Roughly the same amount would go to K-12 schools and community colleges.

But with school districts around California reeling from the phased-in 132 percent increase in payments to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System required as part of the CalSTRS bailout approved[6] by the Legislature in 2014, that funding boost looks inadequate to the California School Boards Association. The group recently released a poll that showed public support for tax hikes on personal incomes of $1 million or more and on corporate income of $1 million or more, which it said would generate $11 billion in annual new revenue.

School boards seek relief from cost of pension bailout

EdSource reported[7] that the CSBA was considering launching a “Full and Fair Funding[8]” signature-gathering campaign to get such tax hikes before voters in November 2020. K-12 schools would get 89 percent of the new revenue and community colleges the remainder.

A May 26 analysis[9] in the Los Angeles Times suggested that each tax hike measure might benefit from focusing on helping public schools.

But voters may question why two major tax hikes are needed less than two years after state leaders boasted about having a $20 billion-plus surplus. Democratic state lawmakers’ nervousness about the optics of adopting a first-ever tax on water when the state treasury was flush led to that proposal’s death [10]even after months of lobbying by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

And the June 4 special election in the Los Angeles Unified School District raised questions about the value of linking tax hikes to school improvements. Measure EE[11] would have imposed a parcel tax based on the square footage of commercial and residential property to generate $500 million a year for the state’s largest school district.

But even though advocates had a much better-funded campaign than opponents, Measure EE got only 46 percent of the vote — far less than the two-thirds necessary for approval. Analysts argued that many local voters simply didn’t trust [12]L.A. Unified to spend the money in the ways that district leaders promised.

- Proposition 13 : https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_13,_Tax_Limitations_Initiative_(1978)

- 25 percent income tax cut : https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/reagan-signs-economic-recovery-tax-act-erta

- Proposition 26: https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_26,_Supermajority_Vote_to_Pass_New_Taxes_and_Fees_(2010)

- Proposition 30: https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_30,_Sales_and_Income_Tax_Increase_(2012)

- Proposition 55: https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_55,_Extension_of_the_Proposition_30_Income_Tax_Increase_(2016)

- approved: http://oughly%20half%20allocated%20for%20K-12%20schools%20and%20community%20colleges,%20and%20the%20remaining%20allocated%20to%20counties%20and%20cities%20according%20to%20current%20property%20tax%20guideline

- reported: https://edsource.org/2019/majority-of-california-voters-favor-tax-increase-on-millionaires-to-fund-schools-poll-finds/612646

- Full and Fair Funding: http://www.fullandfairfunding.org/

- analysis: https://www.latimes.com/politics/la-pol-ca-road-map-california-schools-funding-taxes-20190526-story.html

- that proposal’s death : https://www.latimes.com/politics/la-pol-ca-california-budget-agreement-gavin-newsom-water-tax-spending-20190609-story.html

- Measure EE: https://ballotpedia.org/Los_Angeles_Unified_School_District,_California,_Measure_EE,_Parcel_Tax_(June_2019)

- didn’t trust : https://www.latimes.com/opinion/readersreact/la-ol-le-measure-ee-defeated-ipads-lausd-bonds-20190608-story.html

Source URL: https://calwatchdog.com/2019/06/12/are-voters-ready-to-approve-two-massive-tax-hikes-in-2020/