CA prison population drops below court-ordered level

After an improvised scramble to reduce populations in accordance with federal court orders, Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration has succeeded in lowering the number of state prison inmates to the judicially prescribed level. He largely accomplished that through his Public Safety Realignment program, which was approved by the Democratic-controlled Legislature and implemented in 2011.

After an improvised scramble to reduce populations in accordance with federal court orders, Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration has succeeded in lowering the number of state prison inmates to the judicially prescribed level. He largely accomplished that through his Public Safety Realignment program, which was approved by the Democratic-controlled Legislature and implemented in 2011.

The program shifts lower-level offenders from the state prison system to county jails. It was opposed by Republicans in the Legislature because of the added burdens placed on local governments and taxpayers.

But the precarious achievement of fewer state prisoners also depended on Proposition 47, which was passed by voters last November. It reduced some criminal drug penalties.

But as the prison system struggles to keep numbers low, its string of adverse rulings and legal dealings is far from over.

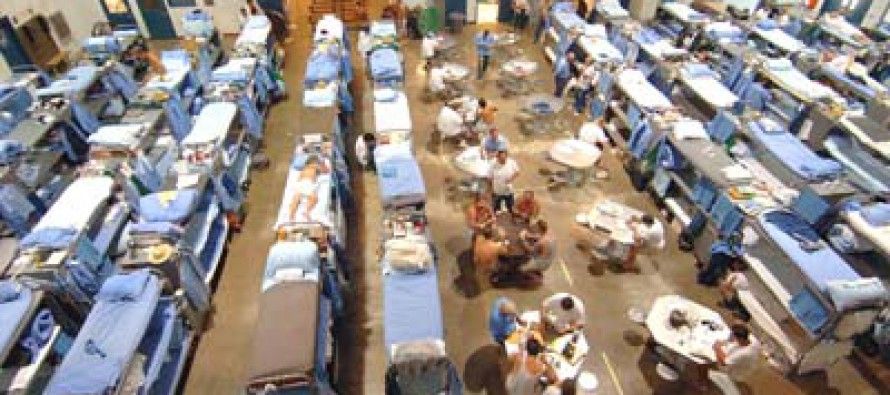

As the Associated Press reports, California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation last Thursday met ahead of time a Feb. 2016 deadline to cut incarcerations at the state’s 34 prisons (excluding juvenile facilities) to 137.5 percent of capacity from the high of 144 percent. Appeasing the courts a full year early marks an important victory for Brown’s realignment policy.

As policies go, however, it has come with a cascade of practical costs. As CalWatchdog.com reported last December, the jails have faced an influx not just of prisoners but of the illegal trade in drugs they bring. Fusion opened a recent report on the intersection of drugs and tech with a bust at a California state prison involving contraband cellphones.

County jails have not only faced problems with smuggling, but the increased staffing and budgetary demands required to deal with taking in state prisons’ relatively tougher and more challenging inmates.

A patchwork result

But as the Los Angeles Times reports, the reduction in the state prison population cannot be attributed entirely to Brown’s success in moving some inmates to county jails. According to population reports cited by the Times, the number of state prisoners sank by 4,000 last year “due to the use of private prisons both in and out of California, enforcement of court orders to expand parole and early release programs, and passage of Proposition 47, making felony drug possession a misdemeanor.”

The impact of private, out-of-state prisons has been substantial. Last year, the Placer Herald recounts, “There were 8,763 California inmates serving their sentences out-of-state in private prisons in Arizona, Oklahoma, and Mississippi. Seven more private prisons operate within California, housing an additional 4,170 inmates.”

But the role of Prop. 47 in fulfilling the judicial mandate has turned out to be central. In a November report, the Times notes, “The corrections agency had projected the inmate population to grow this year because of an uptick in felony convictions, which would eventually push the state above the court-ordered population cap.”

Those numbers are set to be revised next spring because of the passage of Prop. 47. By applying a misdemeanor offense to the most frequent crimes to carry a felony conviction, Prop. 47 took some 40,000 felonies out of the picture. At the same time, it lowered sentences for those crimes from a three-year maximum to a year at most.

For analysts following California’s attempts to curb its prison population, the role of drug crime has been central. As Zach Weissmueller notes at Reason magazine, California’s prison system still operates at around 40 percent higher than capacity. “One reason the state has found it so difficult to reduce its prison population is that the three-strikes law mandates harsh sentences for many drug offenders,” he writes.

He was referring to Proposition 184, which voters passed in 1994. It made tougher a three-strikes law passed earlier that year by the Legislature. This was during the end of the 1980s-early 1990s crime wave that pushed harsher sentencing laws on the books in California and other states, greatly increasing the number of prison and jail inmates.

Prop. 47 and Prop. 36, a 2012 initiative voters passed to reduce the harshness of Prop. 184, both are reactions to prison overcrowding as well as the general reduction in crime of recent years.

Legal complications

Just as Gov. Brown’s administration must consider how to keep incarceration levels below the current benchmark, another round of legal challenges has hit the prison system. In one case, plaintiffs charged state prisons used solitary confinement cells as “overflow” units for disabled inmates.

Ruling in the inmates’ favor, U.S. District Court Judge Claudia Wilken recently determined California violated both the Americans with Disabilities Act and previous court orders, the San Jose Mercury News reports:

“The state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation agreed in 2012 to move the inmates from the cells. Still, Wilken found 211 inmates with disabilities were held in such cells between July 2013 and July 2014 — some for less than a day and others for a month or more.”

This and other legal challenges complicate the move to end prison overcrowding. But the general direction in California is to comply with the federal demands to end what is considered “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Related Articles

Lawmakers take step toward retirement fund for all Californians

State policy makers on Monday inched closer to a state-run retirement system for workers who don’t have access to employer-run

Blueprint Shows Budget Can Balance

MAY 14, 2011 This piece first appeared in City Journal’s new California Web site edited by Ben Boychuk. By STEVEN

Electric skateboard startups set to flourish in CA

With a unique new law on its side, the nascent electric skateboard industry has made California its home. Two new startups —