How much taxpayers lose in special elections

Henry T. Perea’s decision to leave office early cost Fresno County at least a half million dollars.

Henry T. Perea’s decision to vacate his Assembly seat early cost Fresno County a half-million dollars — enough to pay for four sheriff deputies — and has reignited a discussion on the cost of special elections.

The Fresno Democrat announced last year that he’d be leaving the Assembly to pursue a position with the pharmaceutical industry.

In fact, counties are saddled with the cost of special elections regularly. And while they have become less frequent, at least temporarily, a CalWatchdog review of expenses shows that since 2013 counties (and one city) have spent $21.7 million on special elections to replace state lawmakers.

Few would decry a legislator stepping down if the officeholder or his or her family member fell ill. And of course sometimes scandals create a vacancy. But most of the time these seats are vacated by politicians looking to cash in with a high-paying lobbying position, trade up for higher office (perhaps to avoid being forced from office by term limits), which then creates a mad dash to fill the gaps behind them.

For example: In 2013, Curren Price created a vacancy in the state Senate when he won a seat on the Los Angeles City Council, which are elected in odd-numbered years. Holly Mitchell then won Price’s seat in a special election, leaving a vacancy in the Assembly. That vacancy was filled by the current occupant, Asm. Sebastian Ridley-Thomas.

That game of musical chairs cost Los Angeles County $2.4 million. And had Ridley-Thomas and Mitchell not one outright in their respective primaries, forcing a run-off, the cost for the overall costs for the special election would have approximately doubled.

Nonpartisan

Price, Ridley-Thomas and Mitchell are all Democrats, but Republicans do it too. In 2014, Mimi Walters won a seat in Congress in an open Orange County district after former Rep. John Campbell retired.

After winning, she vacated her state Senate seat, which was filled by now-Sen. John Moorlach, costing the county $1.24 million.

One approach

On Wednesday, an Assembly panel will consider a proposal from Asm. Jim Patterson, R-Fresno, which would require that legislators use leftover campaign funds to pay down the cost of the special election they’ve caused, leaving exceptions for health and family reasons.

Perea still has more than $800,000 according to the campaign finance filings from the end of 2015. Instead of giving money to Fresno County, which is allowable under state law, Perea made some political contributions and paid for a few holiday parties.

Other ideas

A measure by Sen. Andy Vidak, R-Hanford, was approved by one panel earlier this month. The bill would require the state to reimburse for the entire cost of the special election for vacancies of state lawmakers. The state used to contribute to the cost of special elections, but has since ceased the practice.

“Fresno County was forced to hold a special election today to fill a vacant Assembly seat, which is costing the county more than a half- million dollars,” Vidak said in a statement last week following the election to replace Perea. “That’s money that could have been used for police, fire, health, education and other vital services.”

Others have suggested the governor appoint a replacement to serve until the next scheduled election. But critics claim that gives the unfair advantage of incumbency to a replacement if he or she decides to run for another term, and gives the governor too much political power.

“Sure, it’s a tradeoff,” said Raphael Sonenshein, the executive director of the Pat Brown Institute for Public Affairs at California State University Los Angeles, noting that if the seat is held only until the next scheduled election then no one would hold the seat for more than two years. “Special elections have very low turnout. It’s at least arguably a budget savings and one less election.”

Turnout

Voter turnout is a persistent issue in California. Some argue that the abundance of special elections contributes to the problem. Most of the special elections have even lower turnout.

In 2013 in Los Angeles, 23 percent of voters turned out for the regularly-scheduled city elections when Price was elected. Later that year, only 5.55 percent of voters turned out to elect Mitchell to the state Senate and then 8.47 percent turned out to elect Ridley-Thomas to the Assembly.

In 2014, the regularly-scheduled gubernatorial election that sent Mimi Walters to Congress drew about 43 percent of voters, while John Moorlach was elected to the state Senate only a few months later with only a 15.42 percent turnout.

Kathay Feng, the executive director of the left-leaning good government group California Common Cause, suggests moving all local elections to the normal presidential and midterm/gubernatorial voting schedule — and during the vacancy, until a successor is elected, the seat could either stay unoccupied or a “caretaker” could be appointed.

“Will a group of people be unrepresented for a short period of time? Potentially.” Feng told CalWatchdog. “But this is insane to elect people by five or six percent of the population and still call it a democracy.”

Cost

The money that is spent on special elections goes to things like: printing ballots, hiring poll workers, securing locations, paying for postage and producing vote by mail ballots.

Many special elections are unbudgeted and all are unplanned and sometimes they overlap. According to Dean Logan, the Los Angeles County registrar-recorder/county clerk, it can be particularly taxing on the county registrar and confusing for voters who could be receiving election packets from the city they live in and then the county a few weeks later, like Los Angeles residents in 2013.

Logan did not advocate a particular path forward, as it’s not his role as registrar. However, he has at least raised questions over the current process and the drain on resources since at least 2010.

“And we already have a crisis of participation even in our regular election cycles, but the turnout in these special vacancy elections is extremely low,” Logan told CalWatchdog.

Term-limits

Some argue that the 2012 modification of term limits, which allowed legislators to spend more time in each chamber, may reduce the number of special elections. While the change hasn’t been around long enough to say for sure, there has been a reduction in special elections since it was passed.

There were 12 special elections (including primary and general/run-off) in 2013, two in 2014, four in 2015 and only one so far this year.

Related Articles

Out-of-state prison costs soar

Jan. 26, 2010 By KATY GRIMES The price tag for California’s out-of-state prisoners has jumped in three years from $20

VIDEO: Republicans can be environmentalists, too

In a conversation with CalWatchdog.com Editor Brian Calle, San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer discusses the importance of preserving the environment

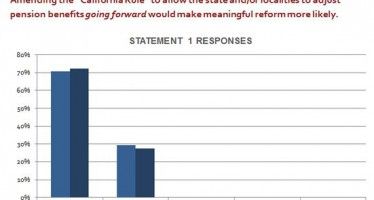

Hoover conference reaches consensus on some areas of pension reform

Today the Hoover Institution released a crucial document in California’s debate over pensions, “California Public Pension Solutions: Post-Conference Report.” The