Lawsuit could expand state control of groundwater

Sacramento Superior Court Judge Allen Sumner just issued a preliminary ruling that Siskiyou County must regulate groundwater well permits along the Scott River in accordance with “Public Trust Doctrine.” This means the water now mainly used by hay farmers also will have to be divided among commercial sports fishing, kayaking, Indian Tribes and tourist-hotel interests.

Sacramento Superior Court Judge Allen Sumner just issued a preliminary ruling that Siskiyou County must regulate groundwater well permits along the Scott River in accordance with “Public Trust Doctrine.” This means the water now mainly used by hay farmers also will have to be divided among commercial sports fishing, kayaking, Indian Tribes and tourist-hotel interests.

The result will be more water shortages as additional political special interests divvy up a limited supply.

The key is the “Public Trust Doctrine,” which was explained in a 1993 report by the California State Lands Commission:

“This Doctrine originated in early Roman law and, as incorporated into English Common law, held that certain resources were available in common to all humankind by ‘natural law.’ Among those common resources were ‘the air, running water, the sea and consequently the shores of the sea.’ Navigable waterways were declared to be ‘common highways, forever free,’ and available to all the people for whatever public uses may be made of those waterways.

“In California, the Public Trust Doctrine historically has referred to the right of the public to use California’s waterways to engage in ‘commerce, navigation, and fisheries.’ More recently, the doctrine has been defined by the courts as providing the public the right to use California’s water resources for: navigation, fisheries, commerce, environmental preservation and recreation; as ecological units for scientific study; as open space; as environments which provide food and habitats for birds and marine life; and as environments which favorably affect the scenery and climate of the area.

“In National Audubon Society v. Superior Court of Alpine County (1983), the California Supreme Court held that the public trust doctrine protects not only navigation, commerce, wildlife and fishing, but also ‘changing public needs of ecological preservation, open space maintenance and scenic and wildlife preservation.'”

Court case

The Siskiyou County court case involves a recent lawsuit brought by the Environmental Law Foundation and the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations against the State Water Resources Control Board and the County of Siskiyou. ELF charged that decreased water flows in the Scott River over the past 20 years are due to excessive agricultural extractions of groundwater that flow into the river, which has harmed fish populations and the navigability of the river for recreational rafting and boat fishing.

The Scott River runs 60 miles in Siskiyou County, located along the northerly state border with Oregon. The Scott River watershed is 800 square miles. About two-thirds is privately owned and a third publicly owned. Forty-five percent is used for forestry, 40 percent for grazing, and only 13 percent for cropland. The Scott River Groundwater Basin is still the only one in all of California that has surface water and groundwater legally defined as “interconnected” (Water Code 2500.5).

The Scott River watershed was “adjudicated in 1980,” meaning the normal court system for water rights settled local disputes. The Siskiyou County Superior Court ruled that all groundwater within 500 feet of the river was subject to court monitoring and restrictions on pumping.

The ruling included safeguards for fish, wildlife and natural river flow under the Public Trust Doctrine. The county issues well drilling permits outside the 500-foot zone, and the court-appointed Watermaster does so within the 500-foot setback. However, the county court has never appointed a Watermaster to govern well permits along the banks of the river within the 500-foot strip.

Writing in the June 26 issue of the California Water Law Journal, Bryan Barnhart said the ELF suit could have sought enforcement by the state Attorney General or the modification of the Siskiyou County court decree to assign a Watermaster for enforcement. Instead, the ELF filed its case in a Sacramento County court seeking to expand the Public Trust Doctrine to groundwater for the first time in California.

The Sacramento Court has issued an interim ruling that California groundwater falls within the jurisdiction of the Public Trust Doctrine. For the interim ruling to stand under final court review, ELF would have to prove that the Scott River is navigable and that sufficient groundwater flows into the river for Public Trust purposes to be impaired. A superior court ruling, however, would not set legal precedent across the entire state.

The Public Trust Doctrine also is supposed to apply only when “feasible.” Whether the Scott River is navigable would have to be a factual finding of the court, as well as whether the Doctrine is feasible during an historic drought.

Inconsistencies with lawsuit

Other developments have not deterred the ELF from filing and threatening lawsuits to agricultural irrigation districts both in Siskiyou County and California’s Central Valley asserting that groundwater falls within the Public Trust Doctrine:

- A December 2000 study in the California Agriculture journal found that 80 percent of the decreased water flows over 48 years in the Scott River are due to “climate change.”

- The recently released California Statewide Groundwater Elevation Monitoring study shows Siskiyou groundwater basins are not “Unmonitored.”

- In May 2013, the county and North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board sponsored a UC Davis hydrologist to develop a groundwater management tool to better manage stream flow conditions in the Scott River.

- Since 2007 the nonprofit Scott River Water Trust has increased river flows by market leasing of farm water during fish migration periods.

Overblown lawsuits?

ELF has also sent letters to 22 water irrigation districts in the state threatening to sue if they fail to comply with a 2009 law requiring the reporting of the measurement of groundwater basins.

A reply came from Robert Kunde, manager for the Wheeler Ridge-Maricopa Water Storage District in Bakersfield: “We comply with the vast majority of what the law requires. We just haven’t filed some paperwork to document it.” He said high water prices due to drought are driving water conservation more than the threat of regulation.

Mark Mulkay of the Kern Delta Water District in Bakersfield said his district has been measuring water in order to charge its customers since 1965.

And nine of the purportedly noncompliant districts have already provided verification to ELF that they are following the law. Where some water districts are too small to be able to afford such paperwork, Ted Trimble of the Western Canal Water District in Oroville is working on creating a regional water plan.

Water Grab?

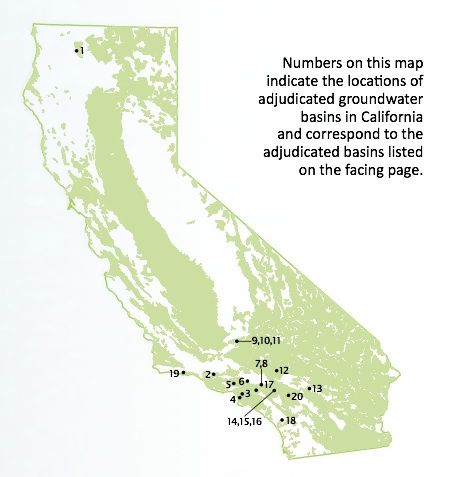

If the ELF case prevails in Siskiyou County, it may not be long before such legal challenges are made against adjudicated urban water basins upon which Southern California depends for about 60 percent of its water supplies in a dry year.

The recent $10.5 billion proposed water bond that recently failed in the California Senate included $150 million for projects proximate to “major metropolitan cities for a river that has an adopted revitalization plan” (alluding to the proposed Los Angeles River Revitalization Master Plan). All such a project needs besides money is more water than the trickle that travels down the concrete-lined flood channels today. And the only place to get that water is from local groundwater basins. Water is turning into an elixir for ecological redevelopment projects.

At stake in the Siskiyou County groundwater case — for both rural and urban groundwater users — may be more than a drop in the bucket. Making room for kayaking in the Scott River may also make way for it in the Los Angeles River by diverting drinking water from residential users to kayakers and water-oriented real estate development in a replay of “Chinatown.”

Related Articles

State’s largest ‘community choice’ energy program takes a hit

The community choice aggregation (CCA) movement has built considerable momentum in California in recent years. In CCA programs, groups of

Unions, Santa Clara Democrats’ disclosure reports don’t match

A Bay Area Democratic campaign committee, which has transferred tens of thousands of dollars to targeted legislative candidates, is facing

California bill would let 17-year-olds vote in all elections

California doesn’t have a particularly high opinion of the maturity of 18-year-olds, who can join the military but who can’t