Study raises doubts about effects of local control in schools

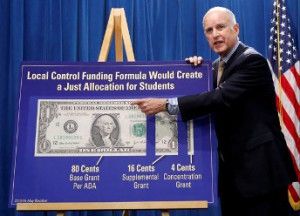

When Gov. Jerry Brown persuaded the Legislature to pass the Local Control Funding Formula in 2013 – the biggest change in public education in California this century – he used two main selling points. The first was that the law would direct more funds to districts that had higher concentrations of English learners, students in foster care and students from impoverished families specifically to help those individuals. The second was that ending dozens of “top-down” state mandates would allow local districts more cognizant of local needs than Sacramento bureaucrats to set their own course in improving schools.

When Gov. Jerry Brown persuaded the Legislature to pass the Local Control Funding Formula in 2013 – the biggest change in public education in California this century – he used two main selling points. The first was that the law would direct more funds to districts that had higher concentrations of English learners, students in foster care and students from impoverished families specifically to help those individuals. The second was that ending dozens of “top-down” state mandates would allow local districts more cognizant of local needs than Sacramento bureaucrats to set their own course in improving schools.

The first point has been the subject of contention for years because some school reform and civil rights groups allege LCFF dollars have been diverted to district general funds, in particular to raise pay for teachers. But until this month, the second point – about the gains that would result from local control – hadn’t been the source of significant controversy.

That may change with the release of a report by a high-profile Canadian education expert – Michael Fullan – and colleague Santiago Rincon-Gallardo. Fullan helped the province of Ontario overhaul its curriculum and, like Gov. Brown, is a well-established skeptic about top-down education reform who has been a sounding board for Golden State education officials in recent years, according to the EdSource website.

But the report he co-authored – entitled “California’s Golden Opportunity” – raises profound questions about California’s venture into local control. Its most striking findings focus on the lack of both enthusiasm for and expertise in crafting education reforms at the local level. The reports also notes how powerful a factor inertia is in the school districts that were surveyed. These same problems have been cited by advocates of “top down” education reform for decades.

The researchers were generous with their praise for LCFF’s basic framework and its inclusionary, open approach to figuring out how to improve schools. They also cite superintendents who prefer elements of the landmark 2013 law to previous policies.

“Even though its implementation has been somewhat bumpy and cumbersome, LCFF is viewed positively across California’s education system – from central offices to school districts,” their report noted. “There is a widely shared perception that the new funding strategy is much better than the older one and that the system is moving in the right direction.”

Districts see local reform plans as busywork

But Fullan and Rincon-Gallardo wrote that their interviews showed the most basic LCFF obligation – having each district prepare Local Control Accountability Plans – was often treated more as mandatory paperwork to be filled out in pro forma fashion than the starting point for pursuing reform.

Fullan and Rincon-Gallardo said the state should provide far more help to local districts in crafting local reforms. One reason: County offices of education in the great majority of the state’s 58 counties weren’t up to the task. The California Collaborative for Education Excellence – the state agency set up to help districts with LCAPs – needs far more resources, they wrote.

While the report notes problems with motivating local officials to pursue reform, it also includes a tough view of LCFF implementation from those at the local level. It noted that district officials interviewed “across the board” complained of a disconnect between what county- and state-level educators were doing and actions that would actually yield “improved teaching and learning in the classroom.”

Nonetheless, State Board of Education President Michael Kirst treated the report as more positive than negative in an email sent to EdSource. Kirst wrote that the report amounted to “confirmation that California is on the right track … . We have a lot of work ahead as we complete implementation of the Local Control Funding Formula and appreciate [Fullan’s] thoughtful and pragmatic recommendations.”

Chris Reed

Chris Reed is a regular contributor to Cal Watchdog. Reed is an editorial writer for U-T San Diego. Before joining the U-T in July 2005, he was the opinion-page columns editor and wrote the featured weekly Unspin column for The Orange County Register. Reed was on the national board of the Association of Opinion Page Editors from 2003-2005. From 2000 to 2005, Reed made more than 100 appearances as a featured news analyst on Los Angeles-area National Public Radio affiliate KPCC-FM. From 1990 to 1998, Reed was an editor, metro columnist and film critic at the Inland Valley Daily Bulletin in Ontario. Reed has a political science degree from the University of Hawaii (Hilo campus), where he edited the student newspaper, the Vulcan News, his senior year. He is on Twitter: @chrisreed99.

Related Articles

State agency struggling to police for-profit colleges

The state talks a big game about policing the for-profit college industry, with legislative proposals to ease student debt

The Capitol’s worst-kept secret

By KATY GRIMES Last August, state Sen. Pat Wiggins, D-Santa Rosa, announced that she would not seek re-election in 2010

Largest U.S. desalination plant nears CA open

California has begun its biggest foray into desalination. Located in Carlsbad, in the San Diego area, the plant has raised hopes