Berkeley's Reactionary Recyclers

By K. LLOYD BILLINGSLEY

When cities outsource services to save money, they often take heat from workers. It’s different in Berkeley, where a revolutionary plan to “insource” services to the city drew the wrath of recycling reactionaries.

Berkeley’s progressive pretensions cannot prevent economic woes and the city recently found itself with a deficit of more than $4 million in its solid waste department alone. Unlike the federal government, the city cannot print money to stimulate the local economy. The city duly sent a Request for Proposal (RFP) for solid waste consultants to help eliminate the deficit.

The respondents included Sloan Vazquez LLC of Irvine, a company experienced in solid waste management and recycling, and which had recently completed a similar project for the city of Santa Monica. Kim Braun, solid waste manager for Santa Monica, called the Sloan Vazquez recommendations “productive” and “very helpful.” She told CalWatchdog that collection route changes had resulted in savings for the city of more than $450,000 on overtime costs and $334,000 on alley cleanup. Santa Monica laid off no workers as a result of the report and is “still implementing” other recommendations, Braun said.

After an interview process, Berkeley selected Sloan Vazquez to conduct the review. The company set out to examine everything in the purview of Berkeley’s solid waste management system. If not a model of fiscal rectitude, it did showcase the city’s commitment to diversity.

The city itself handles residential and commercial garbage collection and manages its own transfer station for the waste. The city also manages some franchised haulers serving the commercial sector and contracts with the non-profit Community Conservation Center (CCC) to process the residential and commercial recyclables. The non-profit Ecology Center (EC), collects recyclables from residential areas, but that is not all they do.

The Ecology Center runs a Climate Change Action program, with services “to both prevent and prepare for rapid climate change.” The center also offers climate change workshops and with its carbon calculator “you can quantify your ‘carbon footprint,’ quantify the change in your carbon footprint when you shift your habits, and connect with others in Berkeley who are doing the same.”

The Ecology Center describes itself as “a community-based non-profit that depends on the generous support of our members and donors.” The “many ways” to support the Ecology Center include donations of money, donations of stock, and “sell your house using Green Planet Real Estate.” The non-profit also enjoys a steady revenue stream from Berkeley, and occupies a special place in the city’s municipal waste system.

Richard Nixon was president and Ronald Reagan governor of California when the Ecology Center began collecting recyclables for Berkeley in 1973. In all that time, nearly 40 years, the city has never put out that service to bid. Waste management services are deemed “public health and safety” concerns, so cities are not required to bid them out. Yet most municipalities do bid out or renegotiate such service contracts every seven to 10 years, in an effort to keep costs down.

Berkeley’s recycling costs remain high. Sloan Vazquez found that Berkeley residents paid 50 percent to 60 percent more than neighboring Bay Area communities. At the time of the RFP, Berkeley was paying the Ecology Center an annual $3.2 million to collect residential recyclables, which EC picks up with six trucks, all painted white. The EC mission states:

The Ecology Center facilitates urban lifestyles consistent with the goals of ecological sustainability, social equity and economic development. We seek to make these goals accessible by providing people with the information they need, the alternatives they seek, and the infrastructure necessary to make sustainable practices possible on a large scale. We aim to make the visionary mainstream. (emphasis added)

When Sloan Vazquez sought the information it needed for its report, however, EC was not forthcoming, unlike all the other groups, including the city of Berkeley itself and the CCC, also a non-profit. The non-profit that offers to quantify one’s carbon footprint was not willing to quantify their own recycling business in any detail.

Sloan Vazquez proceeded with their review, based on the Ecology Center’s $3.2 million – by other accounts $3.7 million – annual charges to Berkeley, and compared those to the city’s known operating costs. Based on this comparison, they recommended that the city “internalize,” that is, take over, the recycling collection service performed since 1973 by the Ecology Center in what can only be described as a sweetheart deal of incredible endurance.

Joe Sloan of Sloan Vazquez calculated that such insourcing to the city would reduce costs by about $1.5 million, even though he found that a single solid waste worker costs Berkeley an average of $113,000 a year in salary, benefits, and other costs. The Ecology Center didn’t like the plan, but Berkeley City Council member Gordon Wozniak called the Sloan Vazquez report “a success” because it had motivated proposals for cutting costs. City Council member Laurie Capitelli was also supportive of the Sloan Vazquez report. According to news reports, so were some union people, who had come up with a similar plan.

Some Berkeley city workers are members of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), and in City Council meeting they praised the Sloan Vazquez report. Ricky Jackson, an SEIU shop steward, said the union’s own report had “some of the same ideas.”

Andrea Lewis, an SEIU member and city worker, told the council that the Ecology Center has a $3.7 million contract, and “that’s not peanuts.” The contract, she said, “has got to go to bid! . . . Why is this contract so different?”

Likewise, Berkeley City Council member Susan Wengraf wondered “why this 3.7 million dollar contract is not bid competitively?” She wanted answers, but none emerged in the meeting. A labor rift offers one explanation. Berkeley is a strong union town, but to paraphrase George Orwell, some unions are more equal than others.

The GuideStar profile of the Ecology Center, based on their 2007 and 2008 IRS 990 forms, shows 21-100 full-time employees and 11-20 part-time employees. The Ecology Center is a union shop and its workers are represented by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), known as the “Wobblies,” a paleo-left group that peaked in the 1920s, even before the Stalin Era. The most famous current IWW member is Noam Chomsky, the American leftist icon touted by Hugo Chavez and Osama bin Laden alike.

“Solidarity Forever,” is a famous Wobbly song, but in March, when Joe Sloan presented his report to Berkeley’s Zero Waste Commission, an IWW mouthpiece accused him of being responsible for “all that is wrong in America today,” and for pitting labor groups against each other.

Ecology Center boss Martin Bourque charged that “the end of nonprofit recycling in Berkeley” would lay off more than 35 union employees. That struck a chord with Berkeley City Council member Linda Maio. She said that the city’s job is to balance the budget and that “our goal isn’t to have anyone laid off from their job.”

EC boss Martin Bourque earned a masters in Latin American Studies and Environmental Policy from UC Berkeley. He has served as executive director the Ecology Center since 2000. Before that he worked for the Institute for Food and Development Policy, also known as Food First. The group is “committed to dismantling racism in the food system” and believes in “people’s right to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems—at home and abroad.”

Bourque talked trash about Sloan Vazquez to anybody who would listen, and proved himself an adept community organizer. He tapped politically correct local PhDs to criticize the Sloan Vazquez report, which some critics said was “incomplete.” That was true in several ways.

The report had not included a detailed breakdown of how the Ecology Center spends the nearly $4 million it gets from Berkeley every year. The report did not include a salary schedule for Ecology Center employees, its board, and executive director Martin Bourque. In an email, CalWatchdog asked Bourque if his Ecology Center makes available that financial and salary information. Mr. Bourque’s belated email response did not answer those questions. Costs and salaries are of considerable interest in this case, but Sloan Vazquez didn’t need that data to perform the job Berkeley wanted.

“We simply looked at what they [the Ecology Center] charge the city to perform the service versus what it would cost the city to do it themselves,” says Joe Sloan. “It was very straightforward.” Sloan says that the Ecology Center “wants to change the terms of the debate, obfuscate, and bluster.” He stands by the report and says that none of Bourque’s local experts “could withstand the scrutiny of an open, public debate on the service issues and costs.”

The controversy would be understandable if Sloan Vazquez had recommended that the city of Berkeley take services they were currently performing and outsource them to some non-union for-profit multinational company headquartered in New Jersey, with possible oil company connections. But that was not what happened.

Rather, the very consultants Berkeley selected, from many candidates, offered the city a way to save money by insourcing recycling services. Despite support for the Sloan Vazquez report from the SEIU and various City Council members, Berkeley has not insourced the recycling service as the report recommends. A more likely outcome is a rate hike, from rates already substantially higher than those in nearby Bay Area communities.

In the end, Sloan’s long experience in recycling and waste management had not adequately prepared him for the conflicts inherent in the system, specifically Berkeley’s longstanding protection racket. In Berkeley’s scale of values, cutting costs takes a back seat to maintaining the recycling status quo, the sweetheart deal with a politically correct, environmentally orthodox non-profit. Observers could be also be forgiven for thinking that Berkeley would rather jack up the rates than do anything less than worshipful of the IWW, Noam Chomsky’s union.

“Power to the people!” used to be the rallying cry in Berkeley. Now it’s “more dollars from the people.”

Related Articles

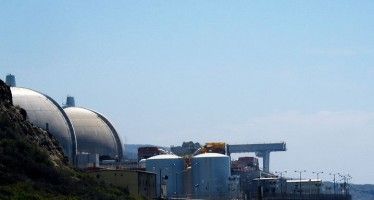

Why green power won’t replace nukes

Last year Southern California Edison mothballed its 2.3 gigawatt San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station. As CalWatchdog.com reported at the

GOP optimistic, even in Bay Area

SEPT. 7, 2010 By DAVE ROBERTS Last week’s candidates forum in Brentwood (the one near the Delta) was an opportunity

Obama sets agenda in SF speech

As part of President Obama’s high-tech trip to California, before donors in San Francisco he set an ambitious agenda for