Calif. retiree health care time bomb is ticking

By Dave Roberts

When discussing California’s exorbitant benefits for state government employees that are threatening to bankrupt the state, much of the focus has been on pensions. And rightly so, with estimates of the unfunded pension liability exceeding $500 billion. But there’s another benefit time bomb ticking away, threatening to blow out the budget in the coming decades: retiree health care.

Health care is by far the largest component in the category known as Other Post-Employment Benefits, which currently has a $62 billion unfunded liability, according to a study released this week by California Common Sense. The numbers are sobering:

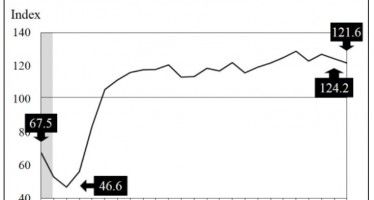

* The cost of benefits for current government retirees has doubled every five years since 1999, on average, increasing from $300 million to $1.58 billion annually.

* The number of retirees receiving medical benefits has increased 11.7 percent since 2008, to 154,500, representing the leading edge of the Baby Boomer generation.

* Life expectancy at age 65 has increased by two years, from 17.2 years in 1990 to 19.2 years in 2009.

* Health insurance premiums have risen 153 percent in California since 2002 — more than five times the inflation rate, according to the latest California Employer Health Benefits Survey.

* Current-year OPEB costs will consume the entire state budget within 35 years.

“In short, more people are earning benefits for longer periods of time at higher prices,” said CACS Research Director Mike Polyako in a press release. “Together, these factors are driving growing concern about how the state will pay for these benefits in the future. The state of California currently pays for retiree health benefits out of its operational budget on a ‘pay-as-you-go’ basis. Historically, that year-to-year approach was manageable. But as the number of retirees and health costs continue to rise, the state will need to find a more sustainable strategy. ‘Pre-funding’ the retiree benefits, or setting aside funding for them today as employees earn them, will attenuate the strain on its budget in the long term.”

Pay-as-you-go

Pay-as-you-go can also be referred to as Wimpy budgeting, from the Popeye cartoon: “I’ll gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today.” The state is not paying the full cost of the retiree health care liability, which is actually $4.74 billion annually, according to a report issued by the state controller.

“The difference — $3.2 billion — is just as much of a cost as the reported expense,” wrote CACS Board Member David Crane in a Bloomberg op-ed. Crane is a Democrat and well-known expert on California budgeting. “But since it wasn’t paid in cash, it becomes an unfinanced liability that will demand payment from future budgets.”

While it would be painful during the state’s ongoing current budget crisis to contribute the additional $3.2 billion each year, it actually would save taxpayers $21 billion in the long run, according to the CACS report.

“A single year of inaction will potentially cost almost $1.7 billion in missed investment savings over 15 years, or over $300,000 per day,” the CACS press release states. “Pre-funding is dictated by the simple idea that the costs of a benefit (such as pensions) should be recognized as they are earned. It also discourages irresponsible political behavior that defers costs to future generations that may not be able to bear them. Finally, pre-funding accumulates secure assets towards paying future costs and supplements them with investment profits.”

The idea of pre-funding retiree health care is not new. In 2006, the Legislative Analyst’s Office issued a report, “Retiree Health Care: A Growing Cost For Government,” which warned, “The costs of providing health care to retired state employees and their dependents — now approaching $1 billion per year — are increasing significantly. Many other public employers (including the University of California, school districts, cities, and counties) face similar pressures. We find that the current method of funding these benefits defers payment of these costs to future generations. Retiree health liabilities soon will be quantified under new accounting standards, but state government liabilities are likely in the range of $40 billion to $70 billion — and perhaps more.”

Starting small

Like many government programs, retiree health care started small. It began in 1961 with the state paying $5 each month per employee, which back then covered most of the costs of a retiree health plan, according to the LAO. Total costs were $4.8 million, representing less than 0.3 percent of the General Fund budget.

For the past 51 years the state has been shifting to future taxpayers the true cost of the liability.

“[T]he pay-as-you-go approach to retiree health care conflicts with a basic principle of public finance — expenses should be paid for in the year they are incurred,” the LAO report states. “This principle requires decision makers to be accountable — through current budgetary spending — for the costs of whatever future benefits may be promised.”

Although this message has largely fallen on state officials’ deaf ears, there have been some pockets of fiscal responsibility. In 2001, the California Public Employees Retirement System set up the California Employer’s Retiree Benefit Trust Fund. It currently manages $2.1 billion in prefunded retiree health care costs and other post-employment benefits for 338 cities, counties and special districts in the state, according to CalPERS spokesman Brad Pacheco. Three state unions — representing highway patrol officers; craft and maintenance employees; and physicians, dentists and podiatrists — have also consented to pre-fund OPEBs.

“We agree that pre-funding for retiree health obligations is smart for employers to consider,” Pacheco said.

The problem is that the contributions are inadequate to meet the obligations for most of those governmental entities that are participating — and many are not participating at all. The CHP trust’s total balance as of a year ago was only $6.5 million, equating to a 0.02 percent funding ratio, according to the report. The contribution rate for the other two unions, which began in July, is just 0.5 percent of payroll.

Most California cities are just as bad, if not worse off. San Francisco has a $4.4 billion OPEB liability, which is zero percent funded, according to CACS. San Jose’s $2.1 billion liability and San Diego’s $1.2 billion liability are both only 9 percent funded. Oakland’s $520 million liability is zero percent funded. Surprisingly, Los Angeles, which has a $6 billion liability, has managed to provide 59 percent funding.

Cumulatively, California and its 20 largest cities have amassed $78 billion in OPEB obligations, but have only set aside $4 billion to pay for them, according to CACS. The total unfunded retiree health care liability for all of California’s governmental entities was more than $118 billion in early 2008, according to the LAO, and is much higher now.

Bankruptcy

One of the ways out of this bind, at least temporarily, is to declare bankruptcy. Last week, a federal bankruptcy judge gave the OK for Stockton to eliminate retiree health care while it’s going through bankruptcy proceedings. Retired Stockton employees had sued in an attempt to stop the cuts.

The last point in Brown’s 12-Point Pension Reform Plan addresses retiree health care. It calls for requiring new state employees to work for 15 years before the state pays a portion of their retiree health care premiums, and to work 25 years before being eligible for the maximum state contribution. Currently maximum coverage kicks in at 20 years. Brown also wants to end the situation in which retirees are paying less for health care premiums than working employees and wherein they aren’t moving to Medicare coverage.

The LAO gave a thumbs up to Brown’s retiree health reforms: “Combined with other proposals in the Governor’s package, which would encourage employees to retire later, this change could dramatically reduce long-term state retiree health costs below what they otherwise would be under current law. Moreover, by reducing retiree health subsidies to future workers in retirement, this change may encourage some workers to retire a bit later, thereby reinforcing other proposals in the Governor’s package.”

The LAO notes, however, that Brown does not address pre-funding retiree health care at either the state or local level.

“Addressing this problem is very difficult when budgets are tight,” the LAO acknowledges, but adds that it’s vital that it be done. “Assuming continuation of the current system of defined retiree health benefits (where governments promise a specific type of subsidy to health benefit costs for public employees in retirement), both the state and local governments should transition gradually over time to requiring employer and/or employee contributions to cover the costs of these future benefits. [T]he Legislature may wish to consider additional steps to require governments to properly fund their defined retiree health benefit systems. Such steps surely would need to be gradual, given the increased near-term budgetary costs they would impose on governments currently coping with significant fiscal challenges.”

Failure to get a handle on runaway retirement benefits will lead to further erosion in state services. But don’t hold your breath waiting for Democratic state leaders to do the right thing by ending Wimpy budgeting and standing up to the all-powerful government unions.

Related Articles

CRA's Linda Barton: Deer In Headlights

FEB. 2, 2011 By STEVEN GREENHUT If California Redevelopment Association President Linda Barton’s presentation Tuesday at a Sacramento Press Club

CA shakedown headed for a breakdown

June 4, 2012 By Katy Grimes California legislators looked as if they were working hard last week, with hundreds of

CA jobs growth continues — with caution signal

California continues to enjoy fairly strong jobs growth — but new data released today (not yet online) by the A. Gary