Reinflating debate about suburbia

By Steven Greenhut

SACRAMENTO — After the housing bubble burst a few years ago, sending real estate prices through the floor in many places, some influential academics and urban planners celebrated the supposed demise of something they had always derided: the suburbs.

In their view, the kind of homes and neighborhoods many of us live in are tacky, ugly, unsustainable blights. “Suburbia represents a compound economic catastrophe, ecological debacle, political nightmare and spiritual crisis for a nation of people conditioned to spend their lives in places not worth caring about,” wrote James Howard Kunstler, a prominent New Urbanist writer who calls for the wholesale reordering of our built environment.

New Urbanists such as Kunstler push for a return to the old city model — people living in high rises and apartment buildings, relying on mass transit and shopping at local stores filled with goods produced in the surrounding area. While they make some good aesthetic points, they essentially believe we should all live in ways that they prefer.

It’s easy to chuckle at them, as they seize on every crisis (housing bubbles, rising gas prices, etc.) to warn of impending calamity, much like those doomsday preachers who are sure that the latest event is a signal that the world is coming to an end.

Control

But while most of us think only about short-term real estate issues, these ideologues have been changing the laws and building codes to mandate their long-term vision. Given the enormity of suburbia, it’s hard to discern the impact of this wide-ranging policy change. But pay attention to debates over new construction, and look at the requirements for higher occupancy densities, small or nonexistent yards, construction focused around transit and other common building mandates. They are designed to make the common form of suburbia obsolete.

“I live where a majority of Americans live: a tract house on a block of other tract houses in a neighborhood of even more,” wrote D.J. Waldie in his 1996 book, “Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir.” Waldie spoke June 3 at the “No Place Like Home” conference in Anaheim, where he described his spiritual connection to the modest Lakewood, Calif., suburb where he has spent his life.

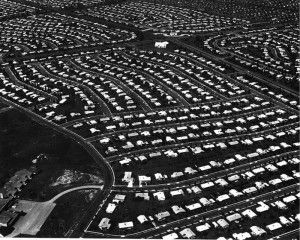

Kunstler described Lakewood, where thousands of homes were built quickly across farm fields after World War II, as “the place where evil dwells,” Waldie said. But it is Waldie’s “beloved community,” a place mocked by snobs but where middle-class people raise their kids and share their lives. These days, the new residents often are immigrants who have come from Mexico or Korea, but they share the same aspirations as those who moved there from places such as Des Moines and Pittsburgh.

The conference defended the ideal of homeownership — something the sponsor, conservative philanthropist Howard Ahmanson, argues is particularly important given “the phenomenon [that] has arisen of syndicates buying up houses in the Inland Empire in quantity for cash, to rent out.” Ahmanson’s father built the Home Savings of America empire that helped many Americans afford a home of their own.

A recent Sacramento News & Review article detailed the results of the reinflating housing bubble, in which ordinary homebuyers have been unable to compete for properties with companies that are buying them in bulk. Sellers, the article noted, won’t risk the uncertainty of dealing with someone who needs to obtain a mortgage when they can take cash from big corporate buyers.

Renters

This situation no doubt will pass, but it is a reminder that, in many places around the world, people have no choice but to spend their lives as renters. The planners who denounce suburbia offer as alternative models the big cities and stylish towns where few Americans could ever afford to live. These are nice places, but not realistic models for most Americans.

San Francisco and Carmel, for instance, are wonderful playgrounds for wealthy people, who enact regulatory and land-use policies that inflate the cost of entry and keep out people of middle-class incomes. Then they suggest their lives are superior to ours because they can walk to work and shop only at environmentally friendly local stores. (Note: Despite their pretenses, even trendy San Franciscans pack the big-box stores clustered under or along the 101 freeway in the heart of the city.)

Urban elitists don’t recognize that their policies helped create the “sprawl” that they disdain. It’s not as if middle-income workers in San Jose would choose to live over the mountain ranges in places such as Tracy, but the growth controls and other regulations that make it tough to build new houses in the Bay Area have so inflated the prices of the existing housing stock that people head to the hinterlands to afford a place of their own to raise their kids.

As speakers noted at the “No Place Like Home” conference, the homeownership ideal is the backbone of a free and democratic society in that it gives people a stake in their community. That’s worth remembering as today’s planners and officials deride suburbia and design what they hope will be a different kind of future.

Steven Greenhut is vice president of journalism at the Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity. Write to him at [email protected].

Related Articles

I'm Singing the California Blues

APRIL 6, 2011 Once known throughout the world as the Golden State, California used to attract people from other parts

Logistical woes mount for high-speed rail

A new special report conducted by the Los Angeles Times has thrown very cold water on the California High Speed

CA governments need caution on fracking investments

May 16, 2013 By Wayne Lusvardi Being the home of Hollywood and Disneyland, news in California always has an element