CA minimum wage may jump 25%

California has made progress in bringing down the unemployment rate. June’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate of 8.5 percent is the lowest since October 2008, according to California Employment Development Department data. Unemployment reached 12.4 percent during the Great Recession, and for much of the past five years it’s been in double digits, including as recently as last October.

While the downward trend has been encouraging, California’s unemployment is still 12 percent higher than the national average of 7.6 percent. And much of the rural area of the state remains at Great Depression levels of unemployment: Imperial County 23.6 percent, Colusa County 15.8 percent, Sutter County 14.7 percent, Merced County 14.1 percent, Yuba County 13.6 percent. In addition, 23 other counties are still suffering double-digit unemployment, including Los Angeles.

While the downward trend has been encouraging, California’s unemployment is still 12 percent higher than the national average of 7.6 percent. And much of the rural area of the state remains at Great Depression levels of unemployment: Imperial County 23.6 percent, Colusa County 15.8 percent, Sutter County 14.7 percent, Merced County 14.1 percent, Yuba County 13.6 percent. In addition, 23 other counties are still suffering double-digit unemployment, including Los Angeles.

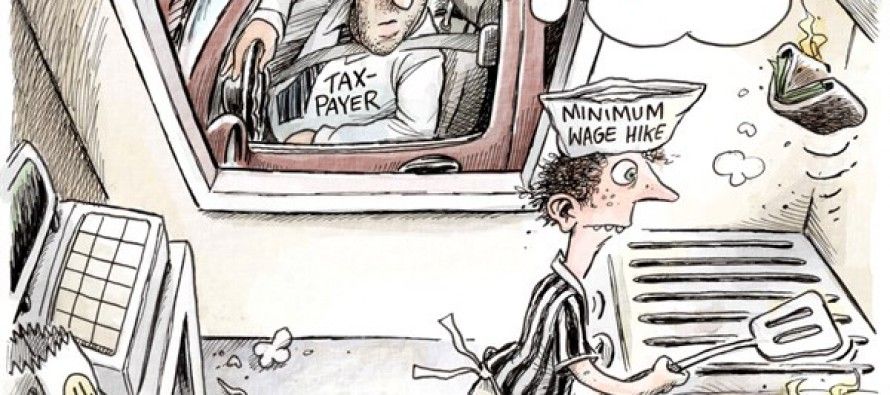

Unfortunately, California’s unemployment rate could be headed back up if a bill significantly increasing the $8 state minimum wage is passed this year. Assembly Bill 10 by Assemblyman Luis Alejo, D-Salinas, would increase it by 25 percent in increments over the next five years: $8.25 per hour starting Jan. 1, 2014, $8.75 in 2015, $9.25 in 2016, $9.50 in 2017, $10 in 2018.

Alejo’s mostly agricultural 30th Assembly District is comprised of cities with high unemployment rates: Gonzales 15.8 percent, King City 13.8 percent, Greenfield 12.8 percent and Salinas 11.5 percent.

Jobs lost when minimum wage increases

Ironically, hundreds of Alejo’s currently employed constituents and thousands more throughout California could be out of a job if his bill passes, according to opponents of minimum wage hikes. The Employment Policies Institute lists the potential damage:

* For every 10 percent increase in the minimum wage, teen employment at small businesses decreases by 4.6 to 9 percent.

* Only 16.5 percent of minimum wage recipients are raising a family on a single income. The rest are teenagers living with working parents, adults living alone, or dual-earner married couples.

* There were 550,000 fewer part-time jobs as a result of the 40 percent federal minimum wage increase between July 2007 and July 2009, according to a Ball State University study.

If Alejo is aware of or concerned about those statistics, he didn’t show it at the Senate Appropriations Committee hearing on Aug. 12. He and his supporters asserted that only good things will come from the 25 percent wage hike.

“The bill means a great deal to me,” Alejo said. “In fact, it was the very first bill that I introduced the first day I was sworn into office. Over the last three years I’ve heard that the time is not right, for one reason or another, to raise California’s minimum wage and give workers an opportunity to better care for their families. However, I argue that the time has not been better. By the time this bill goes into effect it will have been six years since the minimum wage workers have been given a raise. And in this time inflation has skyrocketed.

“Raising California’s minimum wage puts more money into the pockets of workers to spend on clothes, food and other necessities. In other words, it gets reinvested back into the economy. They will spend that additional money, because even with this increase they can’t afford to save it.”

Keeping up with inflation

UC Santa Cruz economics professor Robert Fairlie provided the committee with graphs showing that if the $3.10 minimum wage in effect in California in 1980 had kept up with inflation, it would now be $9.20. Ten states tie their minimum wage to the inflation rate, he said, as does the federal government with Social Security and food stamps.

Fairlie dismissed the concern about job losses due to a minimum wage hike. “The research is actually mixed on this topic,” he said. “There’s a couple of studies done by professor Michael Reich at UC Berkeley, who does not find that an increase in the minimum wage will have a negative effect on employment.”

Fairlie pointed out that an individual making the minimum wage and raising a family of four would need to work 58 hours a week for 50 weeks in order to meet the federal poverty level of $23,000 per year.

“So that’s a considerable amount of effort,” he said. “We also know that the cost of living in California is much higher than the federal level. So without an increase in the California minimum wage, a full-time minimum wage worker will fall even further below the poverty line. So the California minimum wage should not be allowed to continue to erode due to inflation. The economic security of our low-skilled workers is just too important for the state of California to allow that to happen.”

Mitch Seaman, representing the California Labor Federation, argued that increasing the minimum wage would actually be good for business.

“The research is pretty clear that minimum wage increases, and wage increases especially among low-wage workers, do have beneficial effects both in terms of productivity and turnover,” he said. “So those same workers produce more, they do it faster and better, and they stay at their jobs longer. And it produces very real savings that may not wind up in the committee analysis [of the bill], but are no less real and should be considered. We believe the raises are modest and gradual enough to be manageable for employers. But at the same time they make a substantial difference for the workers affected.”

Restaurants may be hurt most

Probably no industry will be affected more by the minimum wage hike than restaurants, most of which were hit hard during the Great Recession. The California Restaurant Association, in an action alert, noted that the wage hike will take effect at the same time that restaurants will also be hit with Obamacare.

“The industry is working diligently to comply with health care reform, but there is no question that will come with enormous costs,” the CRA alert states. “Dramatic cost increases in general commodities, food, fuel and other operational costs have made it more difficult than ever to meet payroll. Additionally, the industry continues to grapple with increasing workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance costs, as well as the consequences of higher sales and income taxes as a result of Proposition 30.”

CRA representative John Ross challenged the notion that California’s minimum wage hasn’t kept up with inflation.

“If you adjust 1956’s minimum wage for inflation and bring it current, you’d be at about $7,” he told the committee. “I’m not suggesting that would be a place that we would want to be right now. But another measure would be to look at the 1996 Living Wage Act, which was an initiative taken to the people by the proponents of this bill. If you took the wages established by that people’s initiative and brought it forward for inflation from 1996 you’d be just under $8.50 today.

“So we think we are in the realm of the historical notion of what an adequate minimum wage is. And while there may be a discussion to be had about adjustment, raising it to $10 over the period suggested here, we think is out of line with where the wage has been over time. The vast majority of workers at the minimum wage in a restaurant are tipped servers who are making substantially in excess of the minimum wage. When the minimum wage goes up, it often comes at the detriment of the very people this bill is trying to help: people who are working close to the minimum wage in other positions at the restaurant.”

Chamber calls it a ‘job killer’

Jennifer Barrera, representing the California Chamber of Commerce, said that AB 10 is on the Chamber’s list of “job killer” legislation. She noted that, while the bill would put the minimum wage on a steady upward trajectory for the next five years, there is no guarantee that California’s economy would follow.

“We don’t know and cannot predict how the economy is going to look in those outer years,” she said. “We don’t know if our economy is going to be booming. We don’t know what the job market is going to look like. And we don’t see the need, when we have a full-time legislature, to lock in a five-year incremental increase in the minimum wage when we can come back and revisit the issue. Historically, the California Legislature has never done more than a two-year bump in the minimum wage, given the presumable difficulty in predicting what the future is going to look like in those outer years.”

On the issue of job loss, she said, “We, of course, believe that it will have a negative impact on jobs. And therefore it will hurt ultimately the California economy, … burdening the state with the benefits that are offered if they do end up losing their jobs.”

AB 10 was sent without a vote to the Appropriations Committee suspense file for further study of its fiscal impact on state government. The bill’s analysis anticipates a hit of $585,000 in the current fiscal year, increasing to $16.3 million annually in four years, from the pay hike for state government’s minimum wage workers. The bill is expected to be brought back for a vote by the end of the month. It passed the Assembly 45-27 on May 30.

Related Articles

Industry confronts new CA computer energy regs

California’s massive computing industry faced the prospect of sweeping changes at the hands of Golden State regulators worried that

San Francisco inequality breeds political unease

As San Francisco’s sharp inequality draws national attention this election year, California Democrats have begun to question how to

Climate policy expansion clears biggest legislative hurdle

An extension and expansion of one of the state’s landmark environmental laws cleared the Assembly on Tuesday — all but guaranteeing