‘Ghosts’ haunt Brown?

JULY 8, 2010

By WAYNE LUSVARDI

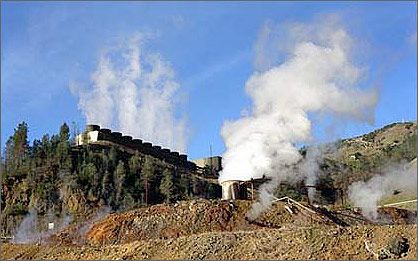

Will a set of Green Power plants in northern California planned in the 1970s under former California Gov. Jerry “Moonbeam” Brown’s administration and shut down in 1990 because they were running in the red come back to haunt third-time gubernatorial candidate Jerry Brown and California’s Green Power law up for review by the voters in November?

Three events surrounding the Bottle Rock and South Geysers Geothermal Power Plants in northern California might call into question the third candidacy of Jerry Brown for governor and the sustainability of AB32 – the Global Warming Solutions Act – on the November ballot for possible rollback by the voters as Prop 23.

The first event came in 1993 when the Los Angeles Times reported that the tab for the $283 million in bonds to plan and build the defunct Bottle Rock and South Geysers geothermal power plants in northern California had been silently picked up by the ratepayers of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

A second event was the 2003 completion of the $250 million Geyser’s Pipeline, planned in 1998, that transported treated sewer water from the city of Santa Clara to the Geyser’s Geothermal field in Lake County, which provided an added source of water for steam to resuscitate the Bottle Rock Plant. The re-opened plant generates 55 megawatts of power for northern California cities.

The third event was the sale of the Bottle Rock plant to a private company in 2001, Bottle Rock Power Corp. The U.S. Renewables Group ended up with the plant in a bankruptcy action and formed a partnership in 2006 to re-open the plant and is transmitting 55 megawatts of green power to customers of PG&E to comply with California’s Green Power mandates under AB32, and making a profit to boot. But the ratepayers of MWD won’t get a dime of reimbursement for paying more than a quarter-billion dollars in principal and interest on the bonds up to the year 2024.

Before understanding how two former “white elephant” geothermal power plants being paid for by Southern California water ratepayers ended up being sold to a profit-making private company to sell green power to Northern California we have to learn a little history.

Turning a Moonbeam into Geothermal Steam

The Bottle Rock and South Geysers plants were conceived in the late 1970s under the then-Gov. Jerry Brown administration following the OPEC oil embargo and long lines at gas stations. At about the same time cheap priced electric power in long term contracts were elapsing to pump water through the State Water Project from Oroville Dam in the north to Lake Perris in the South. A new and hopefully cheap source of pumping power was sought to replace the energy supplied under long-term contracts.

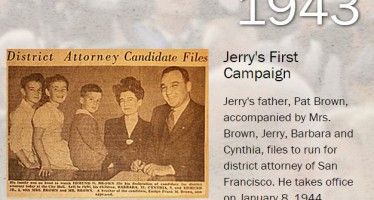

What could be better than geothermal power that generates no air pollution and can produce base load power, not “dirty” coal power and not redundant or intermittent green power produced by solar and wind energy? The plants were intended to provide Jerry Brown with a Green legacy since he left office in 1983 and the Bottle Rock Plant wasn’t completed and started up until 1985. There was no reason for the State Department of Water Resources to get into the risky geothermal power business except to build the Bottle Rock and South Geysers Plants as a Brown legacy. Former Governor Brown ran for U.S president in 1992, following two prior attempts in 1976 and 1980.

According to the Los Angeles Times, the Bottle Rock Plant was initially thought to have enough steam to generate electricity for 30 years but there was insufficient geothermal power to pay off the bonds on the plant. Since the bonds were to be paid off over 40 years, curiously there wasn’t enough forecasted energy production to even last the life of the bonds. There were early reports that it was discovered that insufficient steam pressure was found at the Bottle Rock Plant drill hole before completion of construction. The Bottle Rock Plant lasted only five years and was placed into a “cold shut down” condition in 1990.

The California Energy Commission got its hands metaphorically burnt on the hot rocks of the Bottle Rock geothermal field. Subsequent to the Bottle Rock Plant closure, the Energy Commission adopted new regulations requiring that the potential steam pressure for any newly proposed geothermal power plant be certified before approval.

In 1985, the year the Bottle Rock Plant opened, former Brown campaign manager Tim Quinn was appointed as an assistant general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

How Hot Water Runs Uphill Toward Money

Since the lead agency for the Bottle Rock Project was the California Department of Water Resources, and MWD is the largest customer of the DWR’s State Water Project, the cost of the plant would have eventually just been added to the water rate of MWD. So that is apparently what happened. MWD just buried this extra cost in higher water rates and the public did not learn about this until revealed in the newspapers in 1993.

MWD’s Basic Financial Statement for 2008-09 indicates that it had paid $204.1 million of the bond payments up to that point in time and had $78.757 million remaining to pay through the year 2024 at an interest rate of 5.5 percent. This would amount to $282.85 million in total costs (including interest). Call it taxation with representation but without full disclosure at a public hearing.

The Bottle Rock Plant was shut down in 1990 because it could only generate about 15 megawatts of power instead of its capacity of 55 megawatts. This was not sufficient to generate electricity sales sufficient to pay off the revenue bonds on the plant.

From a Bottle of Rocks to Bottle Rock Power

The Department of Water Resources kept trying to find a buyer for the mothballed Bottle Rock Power Plant in lieu of a permanent shut down and salvage value designation. In 2001, DWR sold the plant for $1.8 million to the Bottle Rock Power Corp., which intended to re-open the plant. The sale included the property interest in the steam field and the ground lease and all transferable permits and licenses. A condition of sale was that the buyers had to establish a $5 million performance bond to cover the cost of decommissioning the plant and land restoration in the future. The new owners were partners from Arkansas and New Orleans and eventually were found to be involved in an illegal pyramid scheme by the FBI. Thus, the plant fell into bankruptcy.

The U.S. Renewables Group purchased an 88 percent interest in the plant with other partners through court proceedings in 2005 for a reported $38 million. The land on which the Bottle Rock Plant sat continued to be owned by the Coleman family, who had originally leased the site to the DWR for the plant as a way to avoid onerous permitting requirements if the plant was built on public-owned land. U.S. Renewables is a Santa Monica-based developer of alternative energy projects and its lead financier was Rustic Canyon Partners, which invests part of the fortune of the Chandler family that built the Los Angeles Times. In turn, U.S. Renewables sold a 50 perent stake in Bottle Rock to the Carlyle Group. (Jerry Brown once lived in an area of Los Angeles called “Rustic Canyon” but that is merely coincidental).

The California Energy Commission approved these sales without any recorded consideration of MWD’s payment of the bonds on the plant. Nor is there any record of MWD appearing before the Energy Commission upon sale of the plant.

Geysers Pipeline was a Pipeline to Money

In 1998, the northern California city of Santa Rosa began planning a “wastewater to energy” project that would transport its unwanted treated sewer water through a 30-mile pipeline to the Geysers geothermal field in Lake County near the hamlet of Cobb in Napa Valley. The city of Santa Rosa planned to “dump” its recycled water in neighboring Lake County under the notion that this was a “green project” that avoided discharging treated “grey water” into the nearby Russian River, even though such water is considered drinkable. Speculation was that Santa Rosa might have not wanted to discharge its water into the Russian River because of perchlorate. The city reportedly does not test for perchlorate in its annual water quality report. The city claims that EPA would have prohibited discharge of treated effluent water into the Russian River. However, discharge into Lake Sonoma that feeds the Russian River would have been permissible if the water was detained in the lake for at least 12 months.

The first day of operation of the Geysers Pipeline was in late 2003.

The Geysers is the largest geothermal energy field in the world and the Bottle Rock Plant is just one of its 22 operating geothermal power plants. The Geysers produces about 1,000 megawatts of electricity, or enough to power a million homes in Sonoma, Lake, Mendocino, Marin and Napa counties. The Geysers is the world’s first and only geothermal system to use wastewater to replenish diminished steam fields.

The Geysers Pipeline Project involves pumping 11 million gallons of treated effluent water up 3,300 feet of the Mayacmas Mountains to replenish the depleted steam in the Bottle Rock Plant area at a total construction cost of a quarter of a billion dollars ($250 million). About $45 million for this pipeline project came from local industry (Northern California Power Agency, Unocal, PG&E and Calpine); state agencies (California Energy Commission); federal agencies (Bureau of Land Management, Department of Energy, Environmental Protection Agency, Economic Development Agency); and Santa Rosa City sewer ratepayers. A consortium of geothermal power providers agreed to pay the $2.8 million annual cost of electricity to pump 11 million gallons of sewer water to the Geyser’s field. The cost of treating the effluent water is born by the city of Santa Clara and other municipalities along the pipeline route. City of Santa Rosa residents will pay the $205 million the city spent on its portion of the pipeline through increased sewer rates over 25 years.

All totaled the old bonds being paid by MWD and the Geyser’s Pipeline Project represent over a half of a billion dollar subsidy to the Geyser’s geothermal field benefiting the Bottle Rock Power Plant as well as 21 geothermal power plants owned by Calpine.

Cost is No Object for Green Power

Projects such as the Bottle Rock Geothermal Power Plant and the Geysers Pipeline tell a story about how cost is almost no object when it comes to government developing Green Power. Not only has a nearly $500 million indirect subsidy to the Geysers and the Bottle Rock Plant been assumed by MWD and the city of Santa Rosa, but the U.S. Renewables Group and the Carlyle Group stand to gain a considerable sum in tax credits for re-starting the Bottle Rock Plant.

All levels of government in California appear to be obsessed to make Green Power work in California no matter the cost or the economic infeasibility. If a project, such as Bottle Rock, doesn’t pencil out then funding from more and more private and public entities are sought until there is enough money to make the projects work. Under such financing schemes the public pays for all the downside costs while the private sector reaps all the benefits. The glossy online promotions by geothermal power generators and the many government agencies never mention all the upfront costs born by the public. That Southern California water ratepayers ended up paying for relatively cheap electricity for northern California cities is unmentionable.

Reminiscent of our recent federal bank bailout, Green Power is “too big to fail.” But in California how much of a hole Green Power puts in the deficit plagued state budget, and on increased water and power rates, is a question that remains avoided by both government and green energy providers.

Geothermal Power is Unsustainable

Green Power is expensive. Even when oil and natural gas prices surge to record highs, it is still typically cheaper to generate electricity by burning fossil fuels or coal than it is using power from wind and solar farms and underground steam.

In 2006, Southern California Edison agreed to pay 6.15 cents per kilowatt hour, plus a premium for peak time power for electricity from renewable sources. DWR power generation charges, excluding transmission costs, on a typical 2010 Edison electricity bill is 3.7 cents per kilowatt hour. Natural gas-fired plants cost 4 cents to 6 cents per kilowatt hour. Solar power can cost up to 30 cents per kilowatt hour. Wind power is all about having relatively cheaper power available for peak months and times of the day but only generates electricity about 5 percent of the time and requires a backup of spinning reserve power that doubles its true cost.

In 2009, the Alameda Municipal Power (AMP) pulled out of an opportunity to add geothermal power from the Geysers field to its energy portfolio because the unit cost, estimated to be from 9.8 cents to 11.7 cents per kilowatt hour, was too high. The cities of Lodi and Roseville, BART and Truckee-Donner Public Utilities District also pulled out. The high price wasn’t the only reason for pulling out. Western GeoPower was proposing to develop a new non-conventional thermal energy field by injecting imported water into hot rock formations deep in the Earth to fracture the rock. Traditional geothermal projects rely on using naturally heated subsurface water and do not rely on an artificial rock fracturing process.

There are many reports that the Geysers field is already past the “peak steam” phase and that thermal pressures are declining despite the imported recycled water. In short, geothermal energy is not sustainable even with massive subsidies and injections of imported water contrary to the popular notion that all green power is self-sustaining. There is some validity to the idea that dumping recycled water into the Geysers is unsustainably removing heat faster than it can recharge.

In 2007, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management coincidentally announced an auction of a 470-acre parcel of land nearby to the Bottle Rock Plant. Co-owner of the Bottle Rock Plant, U.S. Renewables, bid more than $6 million for it (an astonishing $14,000 per acre) for a hilltop. The only apparent way to keep the Bottle Rock Plant sustainable is to continue expanding the land leases and purchases and to inject more and more imported water.

By late 2009, the owners of Bottle Rock had applied to expand by drilling two new well pads with 11 wells each and an injection well on privately-owned land adjacent to the existing plant. By 2009 the plant’s energy production had reportedly fallen to 15 megawatts, close to the 12 megawatts when the plant was closed in 1990.

Green Power Isn’t Always Environmentally Friendly

All energy forms have downsides. Everyone has seen the visual blight and degradation of the desert landscape that wind farms create. Home solar panels are proliferating but don’t live in a hillside community where you have oversight onto the glare of a virtual sea of such reflectors in a new solar housing subdivision, to say nothing about the urban heat island effect in an urban setting. Geothermal power also has its downsides.

One drawback with geothermal power using injection technology from imported recycled water is swarms of daily local earthquakes. It is not unusual to experience hundreds of low level (3.0-4.0) earthquakes in the Geysers.

The Geysers Pipeline also had to obtain pipeline easements across land with sensitive conservation easements.

Another environmental issue with geothermal plants is land subsidence. Steam harvesting leads to a drop in land elevation.

And there is also the issue that by exporting recycled water that local urban water basins will eventually become depleted. So a byproduct of cheap electricity may be greater reliance on expensive imported water that degrades the Sacramento Delta or other watersheds. The 2004 Recycled Water Plan for the city of Santa Rosa actually indicated that “direct discharge” was the highest the best use of recycled water over Geyser’s recharge. It is little wonder that California is perpetually facing a water crisis when it is depleting its local water basins under the rationale of Green Power. The Geysers produces affordable electricity, albeit with massive covert subsidies, but at the expense of local groundwater basins and the Sacramento Delta.

Mothballing Green Power

The story of the Bottle Rock Power Plant is symbolically reminiscent of the infamous movie “Chinatown,” with the L.A. Times Chandler Trust indirectly involved with land speculation, hidden payments on a $283 million bond issue that bails out politicians from failure and subsidizes “get rich quick” schemes, a $250 million recycled water pipeline that recharges the Geysers steam field with questionable benefit to water and sewer ratepayers in the city of Santa Rosa, and the near takeover of Lake County for geothermal plants. Only unlike the infamous takeover of Owens Valley by William Mulholland and the Los Angeles DWP circa 1905, all this has been done in the name of Green Power.

The legacy of how a geothermal steam plant supplying power to northern California cities ended up subsidized by Southern California water ratepayers to the tune of $283 million is likely to be associated with Jerry Brown as he was the one who spearheaded the plan to build the Bottle Rock Plant as his political legacy. And how water and sewer ratepayers of the city of Santa Rosa ended up paying for a $205 million recycled water pipeline to mostly benefit private energy companies and surrounding cities will also likely be associated with Brown’s policies as he was the governor who originally kicked off the green energy revolution in California as well as planning the Bottle Rock Plant. Why MWD and Santa Rosa would both undertake large financial burdens for little to no benefit has never been explained sufficiently.

A metaphor for the Bottle Rock Power Plant is a Hollywood horror movie where the ghosts that haunt a house come back to life. The Bottle Rock Plant is no longer a “ghost plant” but has been re-opened and renamed as “sustainable green power.” But there still are ghosts in the pump house of the Bottle Rock Power Plant that may come back to haunt Jerry Brown’s third bid as the governor of California and with him Assembly Bill32 – The California Global Warming Act – proposed to be mothballed by Proposition 23 on the November ballot.

Key Dates

| December 2024 | MWD last payment on bonds for Bottlerock Power Plant |

| November 2010 | Jerry Brown third run for Governor |

| September 2008 | Energy Commission approves restart of Bottlerock and ownership transfer |

| August 2006 | U.S. Renewable files to repower Bottlerock Plant |

| January 2007 | Jerry Brown elected Attorney General |

| December 2003 | Geysers Pipeline Project operational |

| 1998 | City of Santa Rosa begins planning Geysers Pipeline |

| 1992 | Jerry Brown’s third presidential campaign |

| December 1990 | MWD begins paying off $283 million bonds on Bottle Rock Plant buried in water rate increase |

| November 1990 | Power plant production ends; plant placed into cold shut down state |

| February 1985 | Bottlerock Plant begins operations |

| 1985 | Tim Quinn, former Brown campaign manager, become Vice-President at Metropolitan Water District of So Cal |

| 1980 | Jerry Brown’s second presidential campaign |

| November 1980 | Original application approved by Energy Commission |

| July 1979 | Original plant application filed by Dept. Water Resources |

| 1976 | Jerry Brown’s first presidential campaign |

| Mid 1970’s | In the mid-1970s, the legislature passed tax credits of a whopping 55 percent for wind, solar, geothermal, and some biomass. A 1978 federal law called the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act also helped. |

| 1975 | Brown appointed Tim Quinn, his campaign manager, to Chairman of the California Air Resources Board |

| January 1975 to January 1983 | Jerry Brown two-term Governor of California |

Related Articles

Smelt suit threatens water markets

On June 11, 2014, a coalition of sports fishermen and Northern California groundwater users filed a lawsuit to stop

Can Gov. Brown pluck federal $ for bullet train?

Successful politicians never accept defeat. So it’s not surprising — but still a little startling — that Gov. Jerry

Do tax hikes fix budgets?

JULY 21, 2010 By JOHN SEILER The U.S. and California economies continue to struggle to push up from the Great