Dam-busting plan shrouded in mystery

March 4, 2010

By WAYNE LUSVARDI

Reading about the recent signing of Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement by Governors Ted Kulongoski of Oregon and Arnold Schwarzenegger of California, and U.S. Department of Interior Secretary Ken Salazar, reminds this writer of the tourist traps advertised on huge roadside billboards which are meant to lure motorists that tour the redwoods on U.S. Highway 101 in Northern California and Southern Oregon. One such tourist venue is the “Vortex of Mystery” that is described as a “glimpse of a strange world where the improbable is the commonplace and everyday physical facts are reversed” – see here: http://www.oregonvortex.com/

Environmentalists have dubbed the Klamath River, that runs 250 miles from the volcanic Klamath Lake in Southern Oregon to an ocean outlet near Del Norte in Northern California, the “upside-down river.” This is because it unnaturally drains water from lakes and rivers to irrigate 200,000 acres of farmland and provides electricity for 70,000 homes in Portland and Seattle. But the Klamath River might be termed upside down for very different reasons if California’s proposed water bill is passed on the November ballot.

The proposed water bill package meant to build new dams for drought relief in California contains a weird and paradoxical provision to fund $250 million for part of the demolition of four dams. It is weird because the dams to be demolished are on the Klamath River in Southern Oregon. And it is paradoxical because it would eliminate clean hydroelectric power on the Klamath River and replace it with costly natural gas-fired power plants that pollute the air and allegedly contribute to “global warming.”

You might ask how a so-called California water bill that was meant to combat drought by building two new dams in California end up demolishing four dams in Oregon? And how could a water bill touted as being so “green” end up so brown? And why would so-called urban elites in Portland and Seattle not more strongly oppose the resulting air pollution from the dam removal project equal to 102,000 cars?

To answer these perplexing and mysterious questions we have to first understand what the Cal water bill package on the November ballot is and how it proposes to partly fund the Klamath Basin Restoration Project and Hydropower Settlement Agreement along the Klamath River that proposes to restore the Klamath to a “wild river.”

Dam Removal as a “Lose-Lose” Proposition?

In response to a “normal” three-year drought and a two-year court-ordered shut-down of water deliveries from the Sacramento Delta to Southern California, California legislators have responded with a flotilla of water bills (SB1, SB2, SB6, SB7, SB8 all in 2009) that have been rolled into a water bill package that will be on the November ballot. Included is an $11.1 billon water bond. For an expanded analysis of the water bill go here.

The proposed California water bill will paradoxically facilitate the elimination of approximately $1 billion net worth of clean hydroelectric power in Oregon and incur roughly an equal billion dollars in costs to remove dams along the Oregon reach of the Klamath River. On its surface the proposal sounds like a “lose-lose” proposition.

$250 million dollars of the California water bill package is dedicated for partial funding of the removal of four dams along the Klamath River in Southern Oregon including the hydroelectric facilities that accompany the dams. The remainder of the dam removal costs would come from the ratepayers of the Warren Buffett-owned PacifiCorp that owns the dams ($200 million) and the federal government ($500 million plus), extending out to 2020. The four dams are to be removed reportedly because it would cost Pacificorp $300 million to install “fish ladders” on the dams as a condition of renewing their permit to operate the dams.

But $300 million for fish ladders could be a more cost-effective solution than $1 billion in dam removal costs, the elimination of $1 billion net present value in clean hydro power, significant costs to build new polluting gas-fired power plants in Oregon, and wiping out farmers along the Oregon reach of the Klamath. No mention has been made as to whether dam removal is a way to naturally remove costly silt build-up behind the dams, the first of which was built in 1918 and the last built in 1962. But perhaps the mystery behind such a seemingly costly dam removal project can be explained for other reasons as will be elaborated below.

Klamath as “Upside-Down” River

Environmentalists claim that the Klamath River is turned “upside down” by farming and hydro power that is made possible by the four dams along the Oregon reach of the river. Hay and fertilizer contain nitrogen that mixes with river water. The nitrification process pools in stagnant areas above the dams and results in algae blooms and reduced oxygen as water temperatures rise. The result is a warm river water ecosystem that is ecologically unsupportive to salmon and a dam infrastructure that blocks the ocean water salmon from spawning upstream in fresh water lakes and rivers. “Wilding” the Klamath River would result in colder and more oxygen rich water supportive to Coho salmon, suckers and Bull Trout.

Environmentalists have labeled blue-green algae as “toxic algae” and as the culprit created by dams and farms that warms the river water. Blue green algae is nearly a perfect bogeyman for being labeled “toxic:” it forms a scum pond where stagnant water is, it emits obnoxious odors, and is considered a visual nuisance as well as a potential, albeit remote, health hazard.

But all that damming the Klamath did was shift from a food chain that once was conducive to cold-water fish (salmon, trout, suckers) to that which is now supportive to warm-water fish (bass, sunfish, crapple, catfish, yellow perch, and “walleye”). All that happened was a shift from a grazing food chain to more of a detritus food chain that loves to eat garbage and pond scum. If you want a Coho Salmon and you get a Channel Catfish, you call the river “polluted.” Ecologically, the Klamath can be operated either way: as a warm-water ecology or a cold-water ecology. The trade-off from originally building the dams along the Klamath never was the ecology, but economic and aesthetic values that can be sold to the public for other ends. Salmon “die-offs” and ugly “toxic algae blooms” become the media spectacles shown to the public as justification for removing the dams and hydropower plants. But never mentioned is that removing dams will also destroy the listing warm-water ecology and species of fish along the Klamath River. Which ecology is “endangered?”

Reviving Klamath River Diversion Project?

If there is no rational cost or environmental reason for the removal of the dams what else might explain it? We are left with speculation but it is nonetheless intriguing and not without historical precedent.

What seems to have been long forgotten is what was once called the “Klamath Diversion Project” proposed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation during the 1960s. This ambitious project would have diverted the waters of the Klamath River in Oregon and Northern California to arid Southern California. Initially, this proposal would have allowed for other states in the Southwestern U.S. (Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico and Utah) to receive a larger share of waters of the Colorado River by supplanting Southern California’s allotment of Colorado River Water with Klamath River water. A tunnel running most of the length of the state of California was proposed to carry Klamath River water to the Sacramento River, around the Sacramento Delta, and then southward under the Tehachapi Mountains to the Los Angeles metropolitan area.

The Klamath is the second largest river system in California and carries almost as much water as the Colorado River. The original 1960s diversion plan would have mostly destroyed any salmon runs and habitats and, thus, was originally opposed by the Yurok Indian Tribe and commercial fishermen. Interestingly, in the 1960s the city of Los Angeles reportedly viewed the Klamath Diversion as a “ploy to encourage it to relinquish its claim on the share of the river [the Colorado] it considered its own” (Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert, 1984, p. 270).

Removable Dam Removals?

Another quandary is that there is no guarantee within the presently proposed Klamath Basin Restoration Project for removal of the dams. The U.S. Secretary of the Interior holds the final decision as to whether removing the dams is in the “public interest.” Thus, Oregon Wild, the Hoopa Valley Indian Tribe and The Environmental Center in Oregon are opposing the dam removal project.

Approval by farmers, fishermen and environmentalists is contingent upon consent to the Klamath Watersharing Agreement. Moreover, it is not clear what veto power local governments along the Klamath might have. And the litigation potential of this ambitious project is reportedly considered “high.”

Initial minor opposition to the project by affected urban elites in Oregon and Washington can perhaps be explained for other reasons. In 2000, New York Times columnist and pop sociologist David Brooks wrote a book titled Bobo’s in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There. Bobo’s is a shorthand term for a new social class between the “Bourgeois” and “Bohemians.” What Brooks was referring to were the “greenies” in enclaves like Portland and Seattle who pride them selves in “smart growth” and saving rural farmland from urban “sprawl.” Slowing California-style suburbanization, removing dams and restoring the Klamath River to a wild condition seems justification enough to Bobo’s living in their coastal urban villages in Portland and Seattle.

Water Ouija Board

On its face, the Klamath River dam removal project makes no sense economically or environmentally. What the Klamath River dam removal project indicates is that the California water package bill is possibly larger in scope than we have been led to believe. Everything seems to be in play on the giant regional water chessboard if the California water package bill is passed. The bill would apparently turn “upside down” the entire existing water system in the southwestern U.S., whether it is dam removals in Oregon, the Colorado River Quantification Settlement Agreement (QSA) which divvies up the river water to nearby states; and even perhaps puts on the negotiating table the infamous Sacramento Delta Peripheral Canal Project. As a sign says at the Oregon Vortex amusement in Oregon: “We know practically nothing about anything” (Charles F. Kettering).

Related Articles

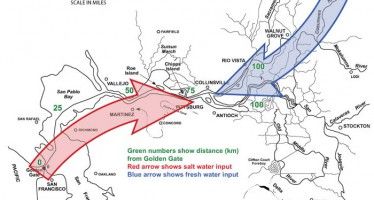

False River dam could halt Delta saltwater surge

California climatologists such as Jeffrey Mount, Peter Gleick and the California Climate Change Center have predicted for some time

How To Do Business With The State

At an event I attended last week, I received a brochure titled “How to do Business with California State Government:

Lawsuit may slow high-speed rail

July 11, 2012 By Dave Roberts With legislative passage last week of $4.7 billion in bonds for the California High-Speed