Do high taxes cost state jobs?

AUGUST 30, 2010

By JOHN SEILER

It’s become a commonplace among many Republicans, conservatives and libertarians that California’s high-tax climate kills jobs. The jobs are either destroyed, driven to other states, or not created here in the first place.

A different view comes from some work done by the Public Policy Institute of California, a think tank that claims to have no ideological tilt yet which seems to lean to the Left. Jed Kolko, PPIC’s associate director and research fellow, has written in an article, “California loses few jobs to other states”:

A recurring complaint about California – and one revived again recently – is that states with lower taxes and fewer regulations are luring businesses, and the jobs they generate, out of state. But the reality is that California loses very few jobs to other states. Business relocations are highly visible when they happen but are a misleading guide to the state’s economic performance. Businesses rarely move out of or into California, and on balance, the state loses just 11,000 jobs a year. That’s just .06 percent of the state’s 18 million jobs. Far more jobs are gained or lost because businesses launch, expand, contract and close.

I checked with several sources on this topic. Esmael Adibi is director of the A. Gary Anderson Center for Economic Research and Anderson Chair of Economic Analysis at Chapman University. Chapman’s bi-annual economic forecasts generally are the most accurate on California and Orange County.

“It’s very difficult to get those numbers,” he told me of jobs leaving California because of high taxes and regulations. The problem, he said, is that most firms don’t advertise why they quit California. And many firms that stay here expand in other states or countries. But because they keep their headquarters and other operations in California, they don’t want to antagonize local people by explaining why jobs were created elsewhere.

“Firms are leaving,” he said. “It’s definitely not good. But there’s no hard data.”

Jonathan Williams, director of the Tax and Fiscal Policy Task Force for the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), agreed that it’s difficult to get exact data on whether taxes, or some other factor, is directly hurting California’s business climate. “It’s hard to break out” the specific factors, he said. But he pointed to ALEC’s recent study, “Rich States, Poor States,” which found that 1.4 million Californians left the state from 1999-2008.

When I brought this up, Kolko told me that “one should not look only at a small set of economic activity.” He said that California has been hit especially hard by the real-estate collapse of recent years because real estate and construction “form a larger part of the economy than in other states.” He added that, “over the past 30 years, unemployment losses have been more severe in California than in the United States overall.”

For jobs losses, Kolko said, “the vast majority are not due to relocation. Relocation is a very small part of economic activity. Nearly all jobs losses are due to existing businesses contracting or shutting down, not moving out of the state. Looking at the firms that may have picked up and moved is not the whole story. It misses the vast majority of jobs in California.”

He said that, “even during the technology boom” of the 1980s and 1990s, “unemployment in California was around one percentage point higher than for the nation. That’s even when California is growing as fast as the United States.”

My own work here at CalWatchDog.com, such as my Jobs Gap calculation, has found that the the gap between California and U.S. unemployment varies with California’s tax and regulation climate. (See also here and here.)

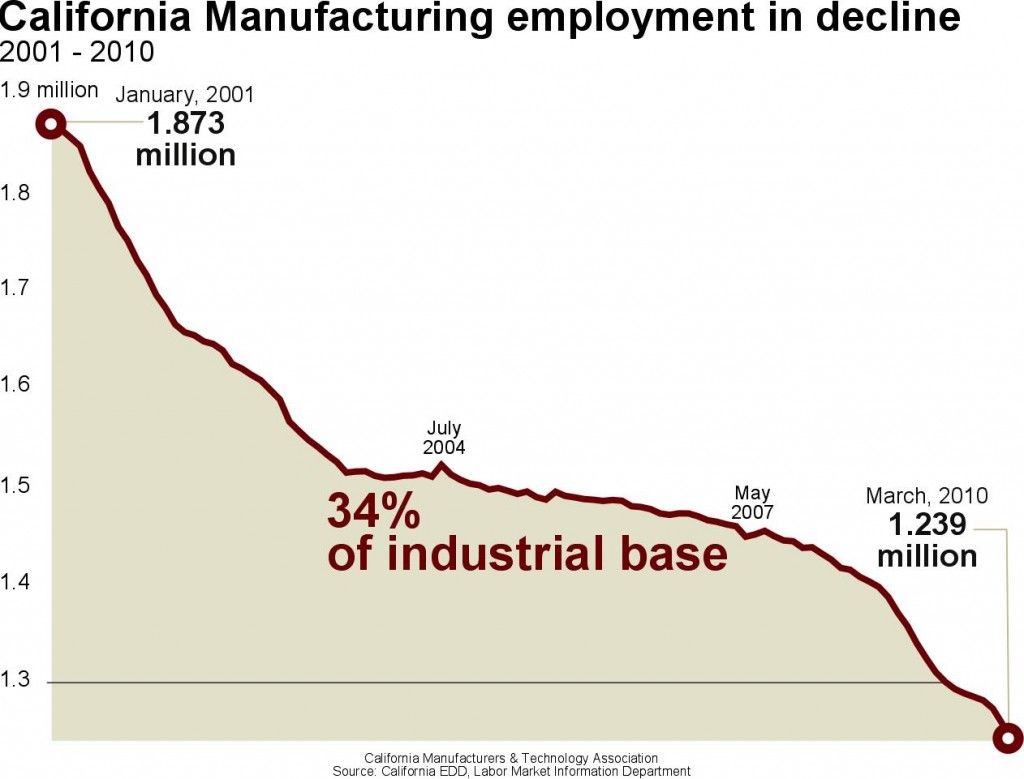

Jack Stewart is the president of the California Manufacturers & Technology Association. “We don’t have anything exactly on high taxes,” he told me. “But manufacturing jobs losses in California, since 2001, have been 634,000. We believe a large reason is high taxes and California’s aggressive regulatory atmosphere.”

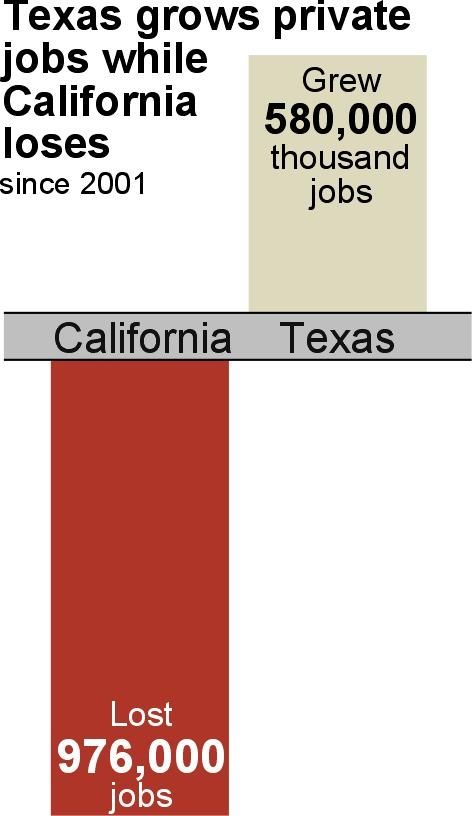

Stewart said to compare California, with its 10.55 percent top income tax, with Texas, which has no income tax. “If people don’t think that taxes matters, since 2001, California has lost 976,000 jobs” overall — not just manufacturing jobs, but all jobs. “During the same time, Texas has grown 580,000 jobs.”

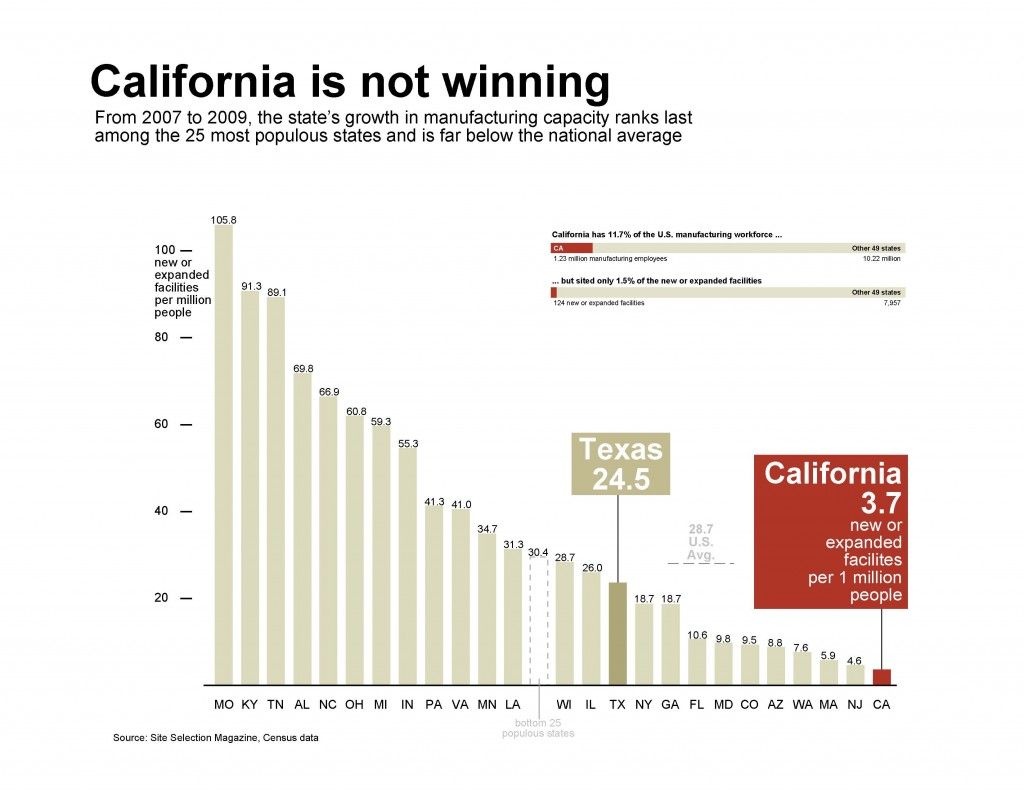

Another comparison, he said, is business “start-ups and expansion.” California currently has 3.7 start-ups or expansion per million people, way below the 28.7 national average. “California has 12 percent of the U.S. population, but 1.5 percent of industrial start-ups,” Stewart lamented.

An “economic state of emergency”

Things seem to be getting worse, according to Joseph Vranich, the Business Relocation Coach. Although his information also is anecdotal, he wrote:

In just two days in July, California lost three company headquarters – Globalstar, Inc. will depart Milpitas for Louisiana, eEye of Irvine will move to Arizona, and TriZetto Group will leave Newport Beach for Colorado – which means this year we are seeing a stunning increase in company disinvestments in California.

In just the first half of the year, there have been 85 such events, nearly double what occurred through all of 2009. An “event” includes instances where companies have closed factories down, moved their headquarters or facilities to another state or country, or targeted locations elsewhere as better places to grow and therefore sent billions of dollars in capital out of state or out of the country….

The exodus of known capital and jobs is the “tip of the Iceberg.” The losses are deeper than are recorded here. California is in an “economic state of emergency” that will only get worse because the state government shows no signs of being less hostile to business and because more companies will be leaving. To the degree I know about some of those companies, under Non-Disclosure Agreements there is no way I can discuss them in advance. In any event, the exodus has reached such an alarming point that California ought to declare a “state of economic emergency” just as we have emergencies resulting from floods, fires and earthquakes. Raising taxes or creating new regulations should be out of the question.

One of our best analysts of California is the well-known author Joel Kotkin. In his August 8, 2010 article, “The Golden State’s War on Itself,” he wrote:

Between 2003 and 2007, California state and local government spending grew 31 percent, even as the state’s population grew just 5 percent. The overall tax burden as a percentage of state income, once middling among the states, has risen to the sixth-highest in the nation, says the Tax Foundation. Since 1990, according to an analysis by California Lutheran University, the state’s share of overall U.S. employment has dropped a remarkable 10 percent.

Those where the years after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger was elected in the 2003 recall election to “terminate” the state’s problems and “blow up the boxes” of government waste, fraud and abuse.

Middle class under assault

In a “Just the Facts” backgrounder on “Are the Rich Leaving California?”, Kolko of PPIC found:

INCOME TAXES AREN’T DRIVING AWAY THE HIGHEST-INCOME HOUSEHOLDS. If high income taxes were chasing away rich Californians, high-income households would be more likely than low-income households to move to states without income taxes—but they aren’t. How come? States without income taxes are cheaper than California in other ways—housing costs, for example—that matter to all types of households, not only to those with the highest incomes. In other words, California does lose people to lower-tax states—but not just because of income taxes.

(Kolko wrote something similar here.)

Kotkin had a different explanation for that: That California, once the welcome home for a large middle-class, and upwardly mobile poor moving up to the middle-class, now has a typical Third World structure: An upper-class that enjoys the bounties California has to offer; a small middle class; and a large and growing lower class that, if it wishes to move into the middle class, leaves the state for opportunity elsewhere. He wrote:

What went so wrong? The answer lies in a change in the nature of progressive politics in California. During the second half of the twentieth century, the state shifted from an older progressivism, which emphasized infrastructure investment and business growth, to a newer version, which views the private sector much the way the Huns viewed a city—as something to be sacked and plundered. The result is two separate California realities: a lucrative one for the wealthy and for government workers, who are largely insulated from economic decline; and a grim one for the private-sector middle and working classes, who are fleeing the state.

What about the “New Economy” of high-tech, eco-friendly jobs? Kotkin reported:

Silicon Valley, for instance—despite the celebrated success of Google and Apple—has 130,000 fewer jobs now than it had a decade ago, with office vacancy above 20 percent. In Los Angeles, garment factories and aerospace companies alike are shutting down. Toyota has abandoned its Fremont plant.

Kotkin also is pessimistic about California’s future because of AB32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, which mandates cutting greenhouse gas emissions in California by 25 percent by 2020. Enacting the law means “virtually assuring that California’s energy costs, already among the nation’s highest, will climb still higher…. [T]he legislation seems certain to slow any future recovery in the suffering housing, industrial and warehousing sectors and to make California less competitive with other states.”

An initiative to suspend AB32 until the unemployment rate drops to 5.5 percent or lower for four consecutive quarters, Proposition 23, is on the November ballot. According to Ballotopedia, Prop. 23 sponsor Assemblyman Dan Logue contended, “The primary issue here is jobs. We need to concentrate on creating jobs and economic prosperity now.”

Opposition leader George Shultz, the former U.S. secretary state, insisted, “While some companies in California have said they’re worried about the cost of the planned greenhouse gas limits, the new regulations will boost the state’s economy by creating ‘clean-tech’ jobs.”

Voters will decide the matter, and the future of California jobs, on November 2.

Related Articles

Municipal Bankruptcy Stalks Stockton

FEB. 27, 2012 By WAYNE LUSVARDI Stockton, California’s 13th largest city, may be moving from “Fat City” to “Mudville.” Both

Pot initiatives join forces

Skittish at the thought of divided loyalties leading rival pot initiatives to defeat, two major marijuana legalization groups united behind

Politics driving CA pension investments

Oct. 5, 2012 By Joseph Perkins The California State Teachers’ Retirement System announced this week that it is sinking $42.8