The Return of Bilingual Ed Plague?

By JOHN SEILER

Bilingual education may be creeping back in California. Yesterday’s Los Angeles Times included an op-ed by Ruben Martinez, a professor of literature and writing at Loyola Marymount University, about a new bilingual ed program at the public school his children will attend.

He wants his twins to grow up bilingual. So he spoke to them in Spanish, while his wife spoke to them in English. Most of the other people in his kids’ lives also spoke to them in English. He was advised on this method by “my colleague Rebeca Acevedo, a linguist and professor of Spanish at Loyola Marymount University.” Martinez writes:

These thoughts weren’t much on our minds when we moved to Mount Washington, a neighborhood with a top-ranked elementary school at the top of the hill. But then we heard that Aldama Elementary School in neighboring Highland Park had recently inaugurated a dual-language immersion program. Maybe I’d finally get some backup for Spanish — and in a public school classroom, no less.

Programs like Aldama’s combine “English learners” with “English proficient” students. Half the day’s lessons are in English, and the other half in the so-called target language. The Los Angeles Unified School District has dual-language programs in Spanish, Korean and Mandarin, and they are increasingly popular; the average growth rate of four or five new programs each year has doubled this year.

But Prop. 227 bans such programs at public schools, Lance Izumi told me; he’s Koret Senior Fellow in Education Studies at the Pacific Research Institute, CalWatchDog.com’s parent think tank. “I see people who are trying to skirt Prop. 227 all the time,” he said. “They’ve been trying to do it since the initiative passed, bringing in bilingual education under the cover of ‘dual immersion’.” That’s the phrase Martinez write is used of Aldama Elementary’s program.

Izumi pointed to a 2008 study of his, “Bilingual Ed Not Dead,” which found pockets of resistance across the state to Prop. 227’s implementation.

I’m all for parents teaching their children however they wish. That’s why there are private and parochial schools, as well as home schools. But public schools, which are funded by taxpayers, are supposed to follow the law, in this case Prop. 227.

As a professor at a major university, Martinez is in the upper-middle class. His children are growing up in an environment that encourages learning. They probably will attend major universities themselves.

Izumi pointed out that bilingual ed — or dual immersion — was allowed for Prop. 227 with a parental waver, but only for one year. “Even dual immersion is supposed to be overwhelmingly in English,” he said. “Even then, it’s a transition. Under Prop. 227, kids who are English-language learners are supposed to become English-only after a year.”

Prop. 227 Raised Test Scores

A genuine improvement in California politics in recent decades was the demise — mostly — of bilingual education becuase of Ron Unz’s Proposition 227 in 1998. It was called the English for the Children initiative. According to Ballotpedia, Prop. 227:

Requires California public schools to teach [Limited English Proficient] students in special classes that are taught nearly all in English. This provision had the effect of eliminating “bilingual” classes in most cases.

According to a 2009 report in City Journal:

Hispanic test scores on a range of subjects have risen since Prop. 227 became law….

Two broad observations about the aftermath of Prop. 227 are incontestable. First: despite desperate efforts at stonewalling by bilingual diehards within school bureaucracies, the incidence of bilingual education in California has dropped precipitously—from enrolling 30 percent of the state’s English learners to enrolling 4 percent….

Second: California’s English learners have made steady progress on a range of tests since 1998. That progress is all the more impressive since school districts can no longer keep their lowest-performing English learners out of the testing process. In 1998, 29 percent of school districts submitted under half of their English learners to the statewide reading and writing test; today, close to 100 percent of the state’s English learners participate. Despite this, the performance of English learners has improved significantly, from 10 percent scoring “proficient” or “advanced” (the top two categories) in 2003 to 20 percent in 2009. Similarly, on the English proficiency test given to nonnative speakers, the fraction of English learners scoring as “early advanced” or “advanced” (the top two categories) has increased from 25 percent in 2001, when the test was first administered, to 39 percent this year.

(This City Journal article also includes a concise history of the bilingual ed boondoggle, as well as reasons why obtaining more exact data on student achievement is difficult.)

Trendy Yuppies

Here’s Martinez describing how the upscale parents pushed for the program:

The initial push didn’t come from working-class immigrant parents but from middle-class newcomers. Courtney Mykytyn, a local mother with a new doctorate in medical anthropology, led the charge for Aldama’s dual-language program. Mykytyn refers to herself and other middle-class, professional parents at the school as the “hummus people,” because that is what they bring to parent potlucks — in contrast to the Doritos or tamales others would bring….

Establishing the program at Aldama took a lot of time and political effort, the kind of time that hummus people tend to have more of. But, Mykytyn says, eventually there was also buy-in from working-class families attracted by promises of higher achievement and cultural pride.

Except, as noted above, bilingual ed does not bring “higher achievement.” It likely doesn’t affect the upscale kids who take it. It’s the “working-class families” who suffer, as always, from schemes like this. Remember the “Whole Language” and “New New math” fads of two decades ago that decimated educations across California until they were jettisoned?

My fear is that these programs will grow into a resurgence of bilingual ed for all students for whom English is not the first language. Bilingual ed teachers get extra training and extra pay, encouraging school districts to advance bilingual ed to get more money.

The programs also enjoy the promotion of groups such as the California Association for Bilingual Education. Here’s how it describes itself:

The California Association for Bilingual Education (CABE) is a non-profit organization incorporated in 1976 to promote bilingual education and quality educational experiences for all students in California. CABE has 5,000 members with over 60 chapters/affiliates, all working to promote equity and student achievement for students with diverse cultural, racial, and linguistic backgrounds. CABE recognizes and honors the fact that we live in a rich multicultural, global society and that respect for diversity makes us a stronger state and nation.

CABE’s vision: “Biliteracy and Educational Equity for All”

The problem is that bilingual ed, after decades in use, failed to deliver the educational achievement that was promised.

Certainly, learning a second or even third language is to be encouraged. But the traditional way of teaching each language by itself, which is followed everywhere else in the world, is the proper method, not bilingual ed.

Poor Kids

Most kids in California schools, of course, do not have a professor as a parent. Many often come from poor backgrounds. Their best hope of making it in American society is learning English, by far the main business language both of the United States and the global economy. When German and Southern Korean business executives get together, they speak English.

That was the reasoning behind Prop. 227: At least get the kids to learn English at a decent level of proficiency. That’ll be a good start. A second language can be taught on top of that.

Another problem is that of funding. As I reported last year, the L.A. Unified School District spends an incredible $30,000 a year per student. Yet the district’s high-school graduation rate is just 40.6 percent, the second lowest in the country after Detroit’s rate. There’s a strong disconnect between cost and performance.

As usual, a government system — in this case, the public schools — doesn’t perform well and costs too much. If the bilingual ed program Martinez is touting spreads to other schools, performance will drop even further.

Kids at the lowest rung of the educational ladder will suffer as a result. Their one chance at making it in America, learning English, will have been taken from them.

“We need to constantly keep an eye on this stuff,” Izumi warned. “It’s amazing how much slips through the cracks.”

Related Articles

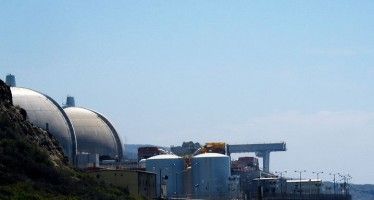

NRC leaves lump of coal in San Onofre’s stocking

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission this week cited Southern California Edison for failing to check the design of steam generators

CA GOP eyes asset forfeiture reform

After sailing through the state Senate, a key criminal justice reform bill with bipartisan support faced its first test in

Studies flunk class-size reduction

(Cross-posted from Union Watch.) Oct. 17, 2012 By Larry Sand It’s time to “just say no” to the small class-size