Bureaucratic Octopus Grabs Bay Area

By DAVE ROBERTS

Like a giant octopus grabbing helpless humans in a horror movie, a new bureaucracy is squeezing the Bay Area.

One Bay Area is a plan to push Bay Area residents out of their cars and jam them into pack-and-stack high rises in the coming decades. The goal: cut greenhouse gas emissions and supposedly help save the planet from global warming.

One Bay Area is mandated by SB 375, the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act of 2008. It was passed by the Democratic-controlled Legislature and signed into law by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican. SB 375 is not as well known as AB 32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006. But SB 375 well could affect Californians’ lives more directly.

One Bay Area is supported by the Bay Area’s liberal politicians, planning bureaucrats, environmentalists, social justice advocates and other elites. The plan is scheduled to be approved by the Association of Bay Area Governments and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission in spring 2013.

Fighting Back

Fighting Back

In the meantime, a few folks, many affiliated with the Tea Party, are putting up a fight, despite the long odds. A number of them raised objections last year at the first round of public input meetings in the nine Bay Area counties. And they did so again this month in the second round’s first meeting in San Francisco.

An additional 2 million people are expected to live in the Bay Area by 2040, bringing the current population of 7.1 million to more than 9 million. This will result in a need for an additional 770,000 to 1 million apartments, condos and houses. That’s a jump from the current 2.6 million units. And, theoretically, an additional 1 million-1.4 million jobs will be created to provide employment for them. That’s up from the current 3.2 million jobs.

One Bay Area is designed to accommodate that growth while meeting the SB 375 goal of reducing carbon dioxide, particularly from cars and light trucks, by 7 percent by 2020 and 15 percent by 2035. The five planning scenarios actually fall short of that goal. So more social engineering will be coming, in addition to One Bay Area’s realignment of land use policies.

The plan attempts to thwart individualistic human nature in the name of communitarian progress. Basically, people who live in the suburbs and drive to work are bad. Those who live in apartment/condo buildings above shops in mass transit-oriented villages where everyone walks, bikes and rides buses and BART are good.

Blowback

Sensitive to the blowback from suburbanites who cling to their McMansions and SUVs, Lou Hexter, the moderator at the San Francisco meeting, was careful to emphasize that the plan “will not prescribe what a property owner must do and will not change the authority of local jurisdictions to make decisions.”

But money is power. The Metropolitan Transportation Commission has the ability to determine where to spend the $256 billion that is slated for transportation improvements in the Bay Area in the next 25 years. If the Bay Area’s nine counties and 101 cities toe the transit-oriented infill development line, they are more likely to get a piece of that funding. If they allow more suburban growth, particularly into farms, orchards and open space, they could lose out.

In any case, those who prefer to drive where they want to go, rather than taking a bus to BART and then another bus to their destination, are likely to suffer in the coming decades. Despite an approximate 30 percent increase in population, under current plans roadway capacity is planned to increase by only about 7 percent between 2005 and 2035. The One Bay Area plan likely will not affect that much.

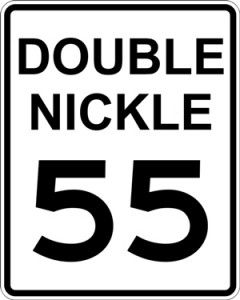

Double-Nickle Speed Limit

On the other hand, mass transit capacity is currently planned to increase by about 22 percent from 2005 to 2035. One Bay Area’s initial vision scenario would increase that to 55 percent.

The idea seems to be to make traffic congestion in the Bay Area, which is already among the worst in the nation, so horrible that tens of thousands of people, perhaps hundreds of thousands, will voluntarily leave their cars at home and instead crowd onto buses, trains and ferries. And if they don’t get sufficiently discouraged from the daily freeway bump-and-grind, the One Bay Area options include increasing parking fees and setting the freeway speed limit at 55 mph (on the rare occasions that such speeds would be possible).

The idea seems to be to make traffic congestion in the Bay Area, which is already among the worst in the nation, so horrible that tens of thousands of people, perhaps hundreds of thousands, will voluntarily leave their cars at home and instead crowd onto buses, trains and ferries. And if they don’t get sufficiently discouraged from the daily freeway bump-and-grind, the One Bay Area options include increasing parking fees and setting the freeway speed limit at 55 mph (on the rare occasions that such speeds would be possible).

In essence, One Bay Area is the San Franciscation of the Bay Area. So it was appropriate that two San Francisco supervisors who also sit on the Metropolitian Transportation Commission provided the opening remarks. They were David Campos (a leader on the board in sponsoring anti-business legislation) and Scott Wiener (who elicited national snickers by requiring nude San Franciscans to place a cloth underneath them before they sit down in public)

“We have to identify what our priorities are to make sure we have effective use of the limited resources, and equitable outcomes so we have a Bay Area that works for everyone,” said Campos.

“We can’t just bury our heads in the sand and pretend we won’t have more people here and don’t need more housing and transit infrastructure,” said Wiener, who touted San Francisco as leading the way in transit-friendly housing. He also put in a plug for High-Speed Rail, “despite the Republican and media feeding frenzy against it.”

Limited Info

The intent of the meeting was to inform the public — or at least the 100 or so people allowed in to each of the nine meetings — about the plan and gain their feedback. But the information provided was limited, general and vague. And public input was mostly circumscribed to fit the pro-urban bias of the plan. Participants were broken into three groups, who then rotated among three rooms that focused on either transportation trade-offs, quality of complete communities or the Bay Area in 2040.

Any doubt on whether the fix was in to turn motorists into an endangered species was dispelled in the transportation room. Participants were asked to select their five most important transportation investments out of nine options — none of which included building more roads. Most of the options focused on mass transit and pedestrian and bicycle paths. Participants were also asked to select “the five most appropriate policies to reduce auto emissions.” The final question asked whether they supported finding ways to improve public transit.

Blood, Sweat and Tears

The presentation on the quality of complete communities was, naturally, skewed in favor of transit-oriented villages on infill land. San Francisco was touted as a model of urban planning by Ken Kirkey, director of planning for the Association of Bay Area Governments. He said, “No place in the region has done more than San Francisco. There’s been a lot of hard work and pain and blood, sweat and tears in the city.”

Not everyone at the meeting welcomed the prospect of sharing or spreading San Francisco’s pain, blood, sweat and tears.

“There are lots of assumptions about complete communities,” said one man. “I hear they will work because we get neighborhood services so people can walk and won’t have to have a car. In my time in San Francisco, the local supermarkets have shut down, corner stores have gone away. People have to drive for services. Nowhere have I seen how those factors are addressed.”

Another man said, “This is one of the most superficial meetings I’ve been to in a long time. Things were skimmed over, videos were at a middle-school level. I’m shocked at the low level of discourse and ideas presented today. We were shortchanged by MTC and ABAG. Let people speak and listen to them.”

Criticism also came from a man who said, “I have a very hard time with this process. This notion of trying to urbanize and turn the Bay Area into Brooklyn seems like madness to me. Forcing people into four-story walk ups. Those are the places people fled from. These are not homes, folks.”

Frankenstein

Frankenstein

One woman warned that One Bay Area could be a Frankenstein’s monster or Pandora’s box. “Whenever you plan and build for two million people, four million people will come,” she said. “Growth has some of its own natural limitations. What you’re doing removes those natural limitations. You are altering things, and there will be many unintended consequences. The densification theories you apply, apply to Europe. They do not apply to the West Coast.”

Despite the fact that nearly three-fourths of the participants live in San Francisco, they were split evenly on whether they support the One Bay Area plan. The tally was 43 percent in favor and 43 percent opposed, according to the electronic polling at the end of the meeting.

They also were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “Changes will be needed in my community and lifestyle to improve the quality of life in the future.” On that question, 47 percent strongly disagreed, which was the top choice. Asked whether the meeting presented the right level of detail on the One Bay Area plan, 62 percent strongly disagreed.

Ironically, for a process touting the virtues of mass transit, at the beginning of the meeting the moderator announced that the shuttle to the BART station would stop running in 20 minutes. “If you need a ride, see us,” said Hexter. “We want to make sure you don’t have to sleep in the auditorium.”

Similar meetings have been scheduled in the coming weeks in the other Bay Area counties:

Regional Advisory Working Group

Tuesday, February 7, 2012

9:30 a.m.

Housing Methodology Committee

Thursday, February 23, 2012

10:00 a.m.

The Housing Methodology Committee meets on the fourth Thursdays of the month at 10:00 a.m.

Related Articles

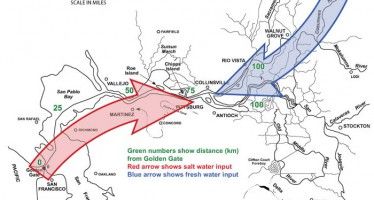

False River dam could halt Delta saltwater surge

California climatologists such as Jeffrey Mount, Peter Gleick and the California Climate Change Center have predicted for some time

Mass transit for poor frowned on in Bay Area

There’s plenty of research that shows that bus rapid transit is far the most cost-effective type of mass transit, with

Boxer’s claim of 56 percent reduction in gun violence includes suicide, accidental death

U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer made the day of conservative media outlets when, in the wake of the San Bernardino massacre,