Ending water wars could spark tax wars

Phil Isenberg wants to end California’s water wars. The member of the Delta Stewardship Council and its past chair wants to connect the cost of water more closely to its users.

Phil Isenberg wants to end California’s water wars. The member of the Delta Stewardship Council and its past chair wants to connect the cost of water more closely to its users.

According to a report by the California Economic Summit, he points out that the cost of water is about $30 billion a year for the state. And it breaks down to 4 percent from federal spending, 12 percent from state spending and 84 percent from water users.

Yearly Water Spending in California by Source (2008-2011) in $ billions

| Local | State | Federal | Total | |

| Water Supply | 14.77 | 1.60 | 0.477 | 16.857 |

| Water Pollution Control | 9.45 | 0.434 | 0.222 | 10.114 |

| Flood Management | 1.32 | 0.574 | 0.254 | 2.152 |

| Fish & Recreation | 0.25 | 0.405 | 0.241 | 0.671 |

| Debt Service on GO water bonds | — | 0.689 | — | 0.689 |

| Total Spending | 25.58 | 3.70 | 1.193 | 30.480 |

| Percent | 84% | 12% | 4% | 100% |

| Source: PPIC, Paying for Water in California, March 2014 (paid for by S.D. Bechtel Foundation) | ||||

Result

The result, Isenberg said:

“Well for one thing, because this is directly contrary to popular perception and most of the recommendations of interest groups who come to Sacramento — or at least the ones who talk to us. … Most of the water decisions about what to build and who pays are made locally in California — and grumpy ratepayers pay the majority of the cost.”

He noted that only $1 billion of that $30 billion the state spends on water comes from bond funds. Yet California spent about $25 billion on five voter-approved statewide water bonds since 2000.

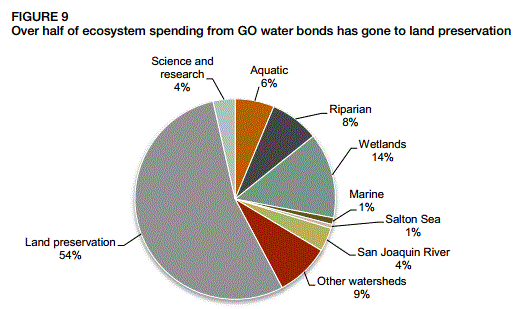

The state hasn’t derived a drop of water storage from these bonds to lessen the impacts of the current combined drought and man-made water shortage; 54 percent of that funding went for open-space acquisitions. Another 14 percent went for restoring wetlands. None went for water storage, as shown by the graph below, from p. 47 of the recent study, “Paying for Water in California,” by the Public Policy Institute of California.

.

.

Because these were statewide bonds, there was no link required between the funding and any water services provided as there is in local water projects under Proposition 218.

Local taxes

The problem leads the PPIC study to the following analysis:

“The flip side of the cost challenge is shrinking revenue alternatives. A series of constitutional reforms adopted by the state’s voters, starting with the landmark Proposition 13 (1978) and followed by Proposition 218 (1996) and Proposition 26 (2010), have made it increasingly difficult for local water agencies to raise funds from local ratepayers, and they have also set up higher hurdles for new local and state taxes to support this sector.”

The PPIC report concluded the tax reforms approved by voters for the local level are “impeding efficient and equitable funding of California’s water system.

Isenberg concurred. “Some provisions like Prop 218 are just nutty, but they serve another goal of the public, which is to reduce costs for themselves,” he said.

In the California Economic Summit summary, “He believes any changes to Prop. 218 will have to show they’ll provide something the public wants just as much: ‘A regular supply of cheap water.’”

The specific reforms sought by the PPIC include:

- Provides that reviewing courts must uphold a public agency’s determination of a need for a tax or rate hike over the objections of any citizen initiative or petition to the Public Utilities Commission or water board;

- Allows “service fees” that don’t service those paying the fee;

- Specially carves out water projects from the two-thirds vote requirement of Proposition 13 so that only a majority vote would be required. In other words, there would be no Proposition 13 for water projects.

The PPIC also wants to use “regulatory fees,” which are limited under Prop. 26 as a source of funding for water projects. This would provide an incentive for government agencies to declare benign environmental substances as toxic as a way to end-run voter review of taxes for water projects.

For example, PPIC proposes a regulatory fee on the agricultural and residential use of fertilizer, which they say contains nitrates that contaminate water. There have been a number of previous attempts to justify taxing fertilizer to fund water projects in California, including the non-existent “blue baby syndrome.” This has compelled agricultural researchers to find ways to escape such taxes by genetically modifying crops to take nitrogen out of the air, as sugar cane does, rather than from the ground.

Tax wars

However, ending California’s water wars might only spark tax wars.

If Prop. 26 were gutted to remove the provision requiring a tax or regulatory fee to benefit those who are taxed, it might undo a recent water rate court decision. Last month a Sacramento judge ruled, based on Prop. 26, that the water rates of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California would overcharge the San Diego County Water Authority by $2 billion over 45 years. Without Prop. 26, the court may have had to rule differently.

Finally, any attempt to change Prop. 13 would be met with string resistance from anti-tax groups, such as the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association. Such groups contend that any weakening of Prop. 13 might lead to gutting the whole proposition, leading to much higher property taxes for homeowners.

Related Articles

Supreme Court Rebukes Crony Capitalism

The following first appeared in City Journal California. JAN. 6, 2012 By STEVEN GREENHUT On December 29, 2011, the California

Court hears objections to high-speed rail

This is Part 2 of a two-part series. Part 1 is here. The first article in this series on the crucial

Solar power causing problems with electricity grid

One theme CalWatchdog.com has covered is how solar power can cause problems to the state’s existing electricity grid. An investigation a year