UFW strong-arms its own employees

By Katy Grimes

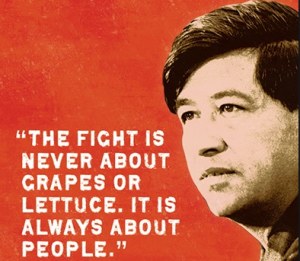

What would Cesar Chavez say? The iconic co-founder of the United Farm Workers union organized across California to improve farm laborers’ pay, benefits and working conditions. Cesar Chavez Day is a state holiday on March 31.

Now the UFW is resisting its own employees’ efforts to improve their situation. In the middle proudly stands longtime UFW ally, Assemblyman Luis Alejo, D-Salinas, who has tried to intervene and mediate for the two sides. But the union bosses are rebuffing his attempts to mediate another neutrality agreement.

UFW split

Last month, farm workers in the Salinas and Watsonville area protested in front of the UFW’s Salinas headquarters over the firing of several organizers, and charged that farm workers were inadequately represented. Joining the protest were some UFW employees, who charged the UFW management and bosses with preventing the employees from forming or belonging to their own union separate from the UFW. For now, the protesters have no official organization or Web site.

Claiming that some of the UFW employees (not the protesters) had been threatened and harassed, the UFW asked a judge to put a halt to such protests. The UFW successfully filed a restraining order on its own employees to keep them from protesting in front of the UFW office, and from organizing, according to the Inland Valley Daily Bulletin. It took an appeal by the UFW employees for the restraining order to be overturned by a higher judge.

Luis Alejo

Luis Alejo

I talked with Alejo about the union split and whether he would intervene. The son of Salinas farm workers, while giving speeches and in Assembly floor debates Alejo expresses impassioned concern for farm workers and their families.

Alejo told me he had been asked by both sides of the UFW to mediate for them last fall. He said he mediated 11 hours one day, 14 hours the next, and helped the two sides hammer out a neutrality agreement. That’s a contract between a union and an employer under which the employer agrees to support a union’s attempt to organize its workforce. In this case, the contract involved the UFW and its employees.

UFW employees speak

The road to organization within the United Farm Workers union has been wrought with obstacles and roadblocks for the UFW employees.

I interviewed two of the organizing UFW employees. Both said they had been so harassed by the UFW for participating in the organizing that they would not allow their names to be used in the story out of fear of future targeted harassment. One of the UFW employees said that, after months of harassment and trumped up workplace discipline, he was fired by the UFW. The second employee still works for the union and fears for her job.

The first employee did not speak English, and used a translator for our discussions. He said he was a field worker for many years, and worked for many good employers, but the UFW was not one of the good ones.

He said the fight between UFW management and UFW employees was only because the employees wanted their own union contract. But the request was met with so much vehemence, the 33 original UFW employees who requested the union contract have been whittled down to 21. Twelve have been terminated or felt they were forced out.

On October 12, 2012, the 33 UFW employees approached three UFW board members after a board meeting, and told them they wanted a union contract.

“We were told, ‘We are the employer, you are the workers,'” the second UFW employees told me. “We thought the union had an understanding of our rights to want a contract,” she said. “They have done this for 50 years [negotiating with large food companies employing farm laborers]; they should have known better.”

Alejo now a ‘contra’

UFW employees heard one UFW director tell Alejo, “I’d tell you to go f*** yourself if you weren’t a legislator.”

“They no longer care about the worker; they are blinded by greed and power,” she added.

“Luis’s role is pro-worker,” she said, referring to Alejo. “He has seen the injustice we’ve gone through. He has been neutral, but stands up for the worker. The UFW now looks at him as a ‘contra.‘ In the eyes of the UFW, he’s the enemy.”

Capitol politics

In a surprising turn of events, earlier this month a controversial labor union bill, SB 25, by Senate President Pro Tem Darrell Steinberg, D-Sacramento, was killed in the Assembly Labor and Employment Committee. Usually, the Senate leader’s bills sail into passage.

Sponsored by the UFW, SB 25 would make numerous and dramatic changes to the mandatory mediation process added to the Agricultural Labor Relations Act in 2002. It would have permitted an agricultural union to serve a request for mandatory mediation upon an agriculture employer to demand bargaining immediately, and forego existing requirements in the law currently used to invoke the mandatory mediation process.

In other words, the UFW would have been granted rights no other labor union has.

Alejo did not vote on the bill, which caused quite an uproar in the already split UFW in Salinas, Alejo’s home turf.

Alejo told the Salinas Californian he had concerns about the bill and had reached out to the union prior to the hearing. “We had a meeting set up for Tuesday [prior to the vote] and [the UFW] canceled,” Alejo said. Shortly after the vote, the UFW was protesting at Alejo’s Capitol office.

UFW bosses’ salaries

UFW bosses’ salaries

The ironic battle between the UFW management and its employees is at the heart of the legal challenges. The UFW employees said Cesar Chavez was a volunteer, and only received a stipend for expenses. But today’s UFW Board of Directors are paid generous salaries.

“UFW President Arturo Rodriguez is paid $105,000 a year,” the UFW employees told me. “Sergio Guzman, the union secretary, makes even more — $110,000 a year.” The UFW offices would not confirm the salaries.

But I was able to independently confirm the UFW Salinas salaries through the California Office of Labor. And UnionFacts reports Rodriguez made $88,379 in 2012. But in 2010 he was paid $125,000, and $105,000 in 2011.

Guzman was paid $105,000 in 2010, and $110,000 in 2011. In 2012, Guzman was paid $85,661.

Union vs. employees

Patrick Semmens with the National Right to Work Committee said it’s not all that uncommon to see a union turn against its own employees when they want to organize. “It shows the hypocrisy that goes on,” Semmens said. “Any possible opposition or skepticism of unions is seen as union busting. But when the shoe is on the other foot, they are the ones calling the horrible names.”

Semmens said unions demonize employers and talk about employee choice, but finds it hypocritical that the UFW won’t let its own employees organize. “This shows they are really only after the dues,” Semmens said.

“They’ve lost focus,” the two UFW employees from Salinas told me. “UFW workers used to do the jobs for the injustice — for farm workers. Now it’s big business.”

Related Articles

Stockton leads tsunami of Calif. bankruptcies

Aug. 27, 2012 By Troy Anderson During Vallejo’s bankruptcy, which began in 2008, the city cut the number of police

Backlash bill would block eminent domain for underwater mortgages

Sept. 14, 2012 By Wayne Lusvardi Will Americans be protected from eminent domain abuses? Eminent domain is where the government

The Gaines emerge as GOP heroes

CORRECTED VERSION Steven Greenhut: The redevelopment lobby — those various corporate-welfare types, bond dealers, consultants, advocates for central planning, assorted