Funds for Moonbeam's sick buildings

SEPT. 2, 2010

By WAYNE LUSVARDI

California newspaper editorials cry out that it is “outrageous” and “unacceptable” that almost a year after Congress granted California $25 million in Stimulus Funds to make state buildings more energy efficient that only one percent of the money has been spent thus far.

That it typically takes a year or more to prepare the drawings and plans for retrofitting buildings with energy improvements is probably beyond comprehension by the public or journalists. And what if government employees need to be relocated during re-construction, how long will it take to arrange that and who is going to pay for that when the state government is broke? And just how many jobs can be created when the paltry $25 million in funds must go toward administrative overhead, engineering assessment and design, possible permit fees, let alone new heating and cooling equipment and building redesign and re-insulation?

Putting the complexities of implementation aside for the moment, the public seems to have a case of amnesia when it comes to the history of building energy improvements in California. Californians need to remember the epidemic of “sick buildings” that followed implementation of California Title 24 building energy standards in 1975 adopted under former Gov. Jerry “Moonbeam” Brown, now running for a third term for governor.

For example, in 1981 the state of California opened the Bateson Building in Sacramento as a model for Title 24 energy conservation standards. Within a year the monument to energy efficiency was the focal point of a $500,000 class action suit on behalf of 1,200 state employees who worked in the building. A wave of sick building syndrome cases and lawsuits followed and continue.

In a 1999 study conducted by the EPA a correlation was found between photocopiers and mucous membrane related symptoms. Photocopiers work best in temperature and humidity controlled and sealed rooms – see here: http://eetd.lbl.gov/IE/pdf/LBNL-42698.pdf

Alice Ottoboni, PhD, staff toxicologist with the California Department of Public Health for 20 years, aptly summed up the situation in her book The Dose Makes the Poison: “Fuel is saved, but people are made ill.”

Indoor air quality did not exist as a public policy issue until government enacted building energy efficiency standards in the 1970s in response to the “oil crisis” of that era. After the enactment of such standards 29 members of the American Legion who attended a convention in 1976 at the Bellevue Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia died of a form of pneumonia that was later dubbed “Legionnaire’s Disease.” The outbreak was traced to a bacterium (Legionella pneumo-phila) in the hotel’s air conditioning system.

The media and science were mostly silent about the role that newer building energy efficiency standards had to play in such lethal events. It was only until such standards mandated “energy tight buildings” with sealed windows and the replacement of interior wall partitions with office cubicles so that conditioned air could flow over the cube walls that what was called “sick building syndrome” began to appear. Building energy standards are an example of economist Tom Sowell’s statement that “there are no solutions, only tradeoffs.”

A cross-sectional study of 2,678 workers from 41 office buildings in Helsinki, Finland definitively showed that “sick building syndrome” highly correlated with office buildings with mechanical ventilation compared with natural ventilation. Office workers in older buildings with movable windows and ceiling-to-floor walls experienced dramatically less sick days than those in “energy efficient buildings.”

Older commercial buildings were designed to allow open windows, cross ventilation and walled-off offices, oftentimes with window air conditioners. In order to retain heat or cooled air, newer buildings have sealed internal environments, central air conditioning systems, and large open floor plates with half-wall modular furniture permitting a wide variety of toxic agents to circulate in the air.

The general principle of toxicology, “the dose makes the poison,” is that exposure to small doses of trace elements is typically an insufficient cause of ill health or life-threatening diseases. The problem with energy tight buildings is that normal trace amounts of pathogens, allergens, or irritants may be confined, concentrated, or continually re-circulated inside buildings so that their effect is magnified.

This “magnifier effect,” not necessarily the toxin itself, is the mostly overlooked root cause of many building-associated environmental maladies such as radon gas, asbestos, and formaldehyde in carpet, mold, secondhand smoke and even anthrax. As the saying goes: “the solution to pollution is dilution.”

If the past scare about the Bird Flu has any credibility, it is likely that vulnerable populations in nursing homes and schools would be hit first and then healthy adult populations in government and corporate office buildings followed by public commercial establishments like restaurants. Older homes and commercial office buildings with old window air conditioners that do not meet newer building energy standards would likely be the least affected.

It is questionable whether such building energy efficiency standards are that effective in reducing the waste of energy in the first place. As pointed out in Stan Cox’s new book, “Losing Our Cool: Uncomfortable Truths About Our Air Conditioned World,” in places such as California there are probably many days during the year where natural building ventilation would save energy over mechanical ventilation. However, this does not mean that we should totally pull the plug on air conditioning as Cox contends, as it saves lives during heat waves, is needed to preserve fresh food, and is needed for high tech clean rooms for semi-conductor manufacturing.

It is curious how the public puts up with increased sick days from influenzas and mysterious “sick building” epidemics due to working in tight office and government buildings but is outraged at the minor annoyance of tobacco smoke in restaurants or the eating of food with transfats. And the public is not outraged at all about the potential threat to human health that such tight building environments potentially pose due to anthrax or small pox exposure by an act of terrorism, however remote. California’s regulated environmental state is a topsy-turvy social democracy where elected officials hold the people accountable for their incorrect environmental behavior at the potential cost of their health. Energy conservation seems to trump health consumerism.

Politicians won’t dare change the energy regulations that are the apparent root cause of much indoor air pollution. An entire industry of so-called experts has been created in both academia and in the engineering professions with a vested interest in the scientific status quo. Nor will they alter the tort law system to prevent the exploitation of a situation that has been created by government regulations in the first place.

Rational argument tends to be ineffective against such entrenched interests legitimated by scientifically vested ideas and powerful cultural forces of environmentalism. Energy conservation is often used to trumpet the environmental successes of politicians without mentioning the downside.

In 2084, the California Legislature may dedicate a new government building to Edmund Gerald Brown, Jr., former governor of California (it may also be known as the “Moonbeam Building”). By then scientists may have figured out how to power the building with moonbeams, the energy from which can be stored in new state of the art batteries. But there still may be one slight problem: such “green buildings” still may make people sick.

Related Articles

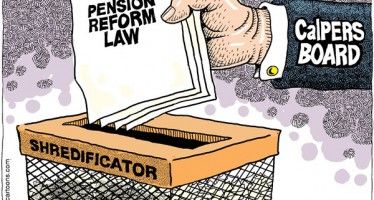

Public pension struggles roil CA

The public pensions crisis has not subsided in California — nor has the conflict that surrounds it. A waves of political,

Silly Bills

Sensitive as I am to the plight of the California legislator during such a difficult economic time, the need to

Alameda County ‘secretary’ will retire wealthy

March 26, 2013 By Katy Grimes Is anyone still buying the idea that government workers are “public servants,” and so