Noted Lawyer Slammed in Judicial Gulag

By RICHARD TRAINOR

When I met Richard Fine in the summer of 2001, he was riding high. Shortly after that he was rotting in jail.

A prominent attorney with a thriving practice in Beverly Hills, in the sunny days of 2001 Fine was a political insider with powerful connections to U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein, Rep. Henry Waxman and political commentator Arianna Huffington.

Fine fought and won important cases, such as one in 1997 against the sale of the Long Beach Naval Air Station to the Chinese Overseas Shipping Company. He was most famous in California for taking on the governor and the Legislature in 1997 for paying state employees before a budget had been passed. In 2003, the California Supreme Court found in favor of Fine when they ruled that employees couldn’t be paid without a budget in effect. That action gained Fine considerable notice and public notoriety as news outlets poured in to cover the story. Both the Los Angeles Times and the Sacramento Bee ran extensive coverage on Richard Fine from 1997 until 2003.

In 1998, Fine took on a case involving property owners in Marina Del Rey. What grew out of this is either “the biggest case of judicial corruption in the history of the United States,” as Fine claims it is, and that he became a political prisoner as the result of it; or it was a personal vendetta being staged by Fine over spilled milk, as his detractors claim. The answer to that is still being debated.

Kenneth Ofgang of the Metropolitan News Enterprise reported at Fine’s disbarment hearing before the State Supreme Court on February 12, 2009, “The hearing judge [Richard Honn] said Fine ‘engaged in what amounts to an almost never-ending attack on anyone (including attorneys and judicial officers) who disagreed with him or otherwise got in his way’.” Fine, Honn said, “kept digging himself into deeper and deeper problems” and failed “to appreciate the harm he has imposed on so many people and on the court system.”

National Review’s Alex Alexiev saw the Fine case as political repression. When Fine’s appeal to overturn his disbarment and was denied by the Supreme Court, Alexiev wrote, “On April 23, 2010, the Supreme Court of the United States denied the petition for ‘stay of execution’ by attorney Richard I. Fine in the case of Richard Fine v. Leroy Baca, Sheriff of Los Angeles County (09-1250). In doing so, the highest court of the land has refused to rectify a clear-cut case of judicial corruption in the state of California.”

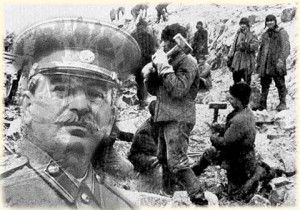

California Gulag

Alexiev saw the case as reminiscent of the Soviet gulag. As he wrote, “[T]he judicial machine moved to get rid of Fine once and for all by having the California State Bar disbar him for ‘moral turpitude,’ a course of action reminiscent of the Soviet Communist regime’s practice of declaring political dissidents criminally insane and locking them up in psychiatric wards.”

On February 26, 2009, Fine addressed a town hall meeting in downtown Los Angeles. Dressed in his trademark diplomat-formal blue suit and one of the colorful bow ties he favors, Fine begins an address to the crowded room, “We have three branches of government here in California: the executive branch, the legislature, and the judiciary. What’s happened in California is that the judiciary has gone bad.”

Fine hardly looks the part of a rabble-rousing revolutionary. He’s more like an academic don you picture from the novels of Saul Bellow or Vladimir Nabokov. Fine was educated at the University of Chicago, where he obtained a doctorate in law in 1964, the London School of Economics and Political Science for another Ph.D. in International Law and the Hague’s Academy of International Law. When we met was also the Honorary Counsel to Norway. He lost that position when he was incarcerated.

Two days after the town hall meeting, Fine held a rally on the steps of the Los Angeles County Courtroom and delivered essentially the same message. Three days after that, Fine was hauled away to jail where he sat in solitary confinement for a year-and-a-half before he was released without charges by the very judge who sent him there and had him disbarred from the practice he’d excelled in for 42 years.

Trust Buster

A former U.S. Justice Department attorney in Washington, D.C. under the legendary Robert Morganthau, Fine headed up the anti-trust division there from 1968-1972 and later went on to specialize in class action litigation when he opened a private practice in Los Angeles in 1974.

In 1998 Fine, took on the case that grew into his crusade to expose judicial corruption. To understand how that grew into such a contentious battle, it is necessary to go back in time to the case that prompted it.

After years of legal maneuvering on a class-action litigation, on June 14, 2007, Fine filed a petition for writ of mandate in the case of Marina Strand Colony II Homeowners Association vs. County of Los Angeles, LASC Case No. BS 109420, as the attorney for the Marina Strand Colony II Homeowners Association. The petition sought to overturn the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors’ approval of an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) in favor of the redevelopment of an apartment complex in Marina del Rey.

Fine’s petition alleged that the EIR violated the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Among the numerous other complaints was Fine’s allegation that Los Angeles County did not receive any positive financial benefit from the project, as required by CEQA. Los Angeles County was the Respondent in the case.

L.A. County won the case.

The judge who ruled in favor of the county was Superior Court Judge David Yaffe, who resigned from the bench in September 2010. Yaffe was also a Los Angeles County employee being paid $47,000 a year in addition to his $176,000 state salary as a Superior Court Judge. He couldn’t fairly judge the case, Fine reasoned, because he had a conflict of interest. The county was paying his salary, and Yaffe was ruling for the county.

Double Dipping

Fine said the judges were guilty of double-dipping by drawing the county salaries. In addition to their voter-approved salaries of $176,000 per year, the L.A. County judges, commissioners and supervisors were also receiving an additional $47,000 per year in salary, retirement and medical insurance. No, these were “benefits”, according to Los Angeles County and the California State Legislature.

No, they weren’t, countered Fine; they were bribes. “They were bribes being paid to judges to throw the case whenever a case came up involving Los Angeles County,” thundered Fine in a videotape from his jail cell with the Full Disclosure network. “Between 2005-2008, not one of the 827 cases involving LA County decided by a Los Angeles County Superior Judge ever went against the county. In 2008, there might have been two that they lost, but we’re not sure because of the way the cases were reported. Any way you look at it, it’s one hell of a track record: 827 to 2, or 829 to nothing.”

In 2008, Yaffe ordered Fine to reveal his assets and pay $46,000 to the county in order for Fine to receive his legal fees on the Marina Strand case. Fine refused and Yaffe threw him in jail.

The Fine-Yaffe tug-of-war might be dismissed as a nasty personality clash that grew into dysfunctional proportions if it didn’t involve such basic questions as due process, habeas corpus, and the passage of ex post facto laws by the state legislature.

In fact, it does: Fine was held for a year without charges, ergo the habeas corpus question. And Fine brought an action against L.A. County for the illegal payment of county employees deciding public cases, including the Board of Supervisors and L.A. County judges. At the time, such payments were prohibited under the state constitution.

Silent Mainstream News Media

During his incarceration, the Los Angeles Times and the Sacramento Bee were notably silent. Instead, Fine’s case was taken up by a woman named Leslie Dutton who posted a number of videos of Fine on Full Disclosure.

The L.A.County Sheriff, Lee Baca, was threatened with a lawsuit before Dutton was allowed access to Fine. Judicial Watch, the public interest law firm, filed the suit on her behalf in late 2009. As Judicial Watch’s Connie Ruffley talked to me about Ernie told me about the actions of Ernie “Stirling” Norris, “When Ernie, the lead attorney for Judicial Watch in California, was contacted by Sheriff Baca, he was asked, ‘What will it take to make this go away?’ Ernie said, ‘Let Leslie Dutton in to tape some interviews with Richard Fine’.”

The judges had their defenders, too. Shaun Martin, a professor of law at the University of San Diego, posted this comment on the California Appellate website on October 15, 2008 when Fine won an appeal against the judges for the dual salary question: “It’s bad enough that your investments are plummeting, your house is worth only a fraction of what you paid for it, and your retirement accounts are completely tanking. But, in the midst of all of this, the Court of Appeal publishes this opinion…. which reverses the trial court and threatens to take away a large amount of money from state court judges not only in Los Angeles, but across the state as well.”

Then Martin waxed prophetic. “Moreover, as a practical matter, at the end of the day, I think it very likely that state court judges don’t have much to worry about from this one, since there’s …a strong likelihood that, if nothing else, the Legislature will step in to clean this problem up and make sure that judges get their benefits.”

Retroactive Immunity

In the summer of 2009, the Legislature passed a bill giving the supervisors and judges retroactive immunity from judicial prosecution, civil liability and disciplinary action, ergo the ex post facto question for the dual salaries. When Senate President Pro Tem Darrell Steinberg, D-Sacramento, was asked about it, he said, “Yeah, we passed a bill restoring their benefits.”

Steve Ipsen, a deputy district attorney with Los Angeles County, seems deeply troubled by some of the precedents he sees in the Fine case. As he told Dutton in an on-camera interview, “When the employer [Los Angeles County] is paying the judge who is making the decision regarding the employer, any appearance of impropriety must be avoided. If even the perception of pressure is there to decide favorably for the county, it’s a very grave danger.”

Richard Fine is now working as an independent strategic consultant for a private firm in Los Angeles. He is keeping a low profile, at least for the time. He is planning his own strategy of getting his license to practice law restored. Whatever chance he might have of doing so and bringing an action against the judges who jailed him for exposing their dual salaries is unclear. Although the limelight around him may have dimmed considerably since the days when he regularly won his cases, the reflected light of Fine’s lonely battle burns bright.

Related Articles

Being CalPERS means never having to say you’re sorry

Jan. 20, 2013 By Chris Reed So CalPERS is found to allow ridiculous, outrageous double-dipping by salaried employees that boosts

iPads in LAUSD just small part of CA school bond scandals

The GOP assemblyman who’s upset about the misuse of 25-year borrowing to pay for hundreds of millions of dollars worth

Cal State Presidents Receive Perks and Benefits Worth 50% of Base Pay

MARCH 26, 2012 By JOHN HRABE California State University presidents receive perks and benefits worth as much as 50 percent