Delta tunnel is a big drain compared to bullet train

By Wayne Lusvardi

Who could have guessed it? A proposed water conveyance tunnel through the Sacramento Delta is a greater economic boondoggle than the California High-Speed Rail Authority.

That’s the conclusion of Jeffrey Michael, director of the Forecasting Center of the University of Pacific Eberhardt Business School. Michael’s conclusion comes from a preliminary cost-benefit study of the proposed Bay Delta Plan he conducted without any outside funding source.

The benefits-to-cost ratio of the California High-Speed

Rail Authority is five times higher than the proposed Bay Delta water conveyance tunnel. The Delta tunnels would be a loser generating only $1 in benefits for every $2.50 in costs, compared to $2 in benefits to $1 in costs for the bullet train boondoggle (according, at least, to train proponents).

The money tunnel

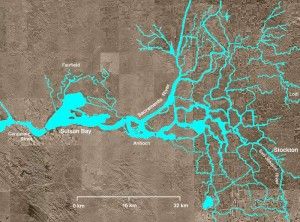

The “Through-the-Delta Tunnel” is a proposed project to convey water directly through the Sacramento Delta in a massive underground tube, rather than around the Delta in a Peripheral Canal.

In wet years, the tunnel would bring water to reservoirs and underground water banks for use by farms and Southern California cities in dry years. The tunnel has been designed to be very large in order to convey a huge volume of excess water during wet years.

Local Delta farmers, fishermen and environmentalists don’t want a surface canal around the Delta. So a subsurface tunnel project through the Delta was proposed. But, at $14 billion, a tunnel is the most costly alternative. Have farmers and cities been compelled to pursue the most costly alternative for the project, only to have the tunnel option blamed as economically infeasible?

Voters shot down the proposed Peripheral Canal in 1982. Thirty years later, this has resulted in California only having about a half-year of water storage in the combined state and federal water systems in California to weather a drought. Southern California cities have had to learn to manage water by conservation rather than water storage.

Should the project be built at all?

Given his conclusion of the lack of economic feasibility, Michael asks the question: “Should the Delta project be built at all?” But this also raises the question: Is it too late to stop it?

Michael’s cost-benefit study may be too late because AB 39, the Delta Reform Act, has already been signed into law. An official cost-benefit study by economist David Sunding of the University of California won’t be released until the Bay Delta Plan is in final form. This is unlike the high-speed rail project that has released updated cost-benefit studies as the project has evolved in its planning phase. Thus, Michael has taken it upon himself to do an up-front cost-benefit study for the benefit of the public.

The Delta Reform Act is based on the “co-equal” goals of the conservation and management of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta ecosystem and improving the current supplies and reliability of water conveyed through the State Water Project and the federal Central Valley Project. The Delta Plan would not “restore” the Delta because the Delta was originally an occasional inland sea that created flooding and havoc on the economy.

By adopting the co-equal goals of the Delta Plan, the state Legislature and governor have inadvertently nearly eliminated any ongoing economic consideration of the project. The proposed Through Delta Tunnels are estimated to cost about $14 billion. The rehabilitation of the Delta ecosystem is estimated to cost about $4 billion. But the net economic feasibility — comparing costs and benefits — is about $500 million in net benefits and $1.25 billion in net costs, according to Michael’s rough study. That means that the costs of the proposed through-Delta tunnel are about 2.5 times the benefits to both water users and to the Delta ecosystem.

Michael points out that the original Bay Delta Plan in 2006-7 called for a “$3 to $4 billion canal that would ‘restore’ water exports up to 6.5 million acre feet on average.” An acre-foot of water is enough, for one year, to supply two urban households; or irrigate one-third of an acre of farmland. Now, he says in emails to me: “The cost has increased 3 to 4 times, it yields one million acre feet less water in the best case scenario and water demand is declining — and planners have finally gotten real about the long-term demand trends.”

“It is completely logical that people who supported the (Delta) vision 5 years ago would oppose the plan now. Anyone who isn’t seriously reconsidering their position in light of changed facts isn’t being rational,” says Michael. “I am not saying that I necessarily support the idea that Southern California should write a multi-billion-dollar habitat check, either. I think taxpayers and ratepayers deserve to have an alternative explored.”

Scare tactics instead of economics

Michael further says that sloganeering and scare tactics can’t substitute for sound economics: “For four years I have said I will support a canal if the state can demonstrate that it makes sense in a real statewide benefit-cost analysis. I would tell the Delta folks it is for the greater good of California.

“But canal and tunnel supporters just state that it is for the greater good of the state with slogans (’25 million new people’) or scare tactics (‘an earthquake will rupture the Delta levees and cause the economy to run dry!’). Maybe, but a canal or tunnel doesn’t protect energy, transport, etc.

“They — the Delta Stewardship Council — have refused to conduct or at least release a cost-benefit analysis. Taxpayers should be outraged by that, no matter where they live.”

Are ‘co-equal goals’ and cost-benefit compatible?

Mike Wade, head of the California Farm Water Coalition, believes that the above cost-benefit study ignores that policy makers have already passed laws requiring the “co-equal goals” of reliable water supplies and ecosystem protection for the Delta.

In response to Michael’s cost-benefit study, Wade left the following comment online:

“A closer look at the two reports by UC Berkeley’s David Sunding and UOP’s Jeffrey Michael reveals that the study Sunding provides is an in-depth analysis on the economics of California water and the benefits that result from an enhanced water supply. This water supply, along with a restored Delta ecosystem, is the basis for the work currently being conducted by the Bay Delta Conservation Plan. Unfortunately, the report by Jeff Michael fails to assign any value to meeting either of the co-equal goals, which is the entire basis for the existence of BDCP.”

Of course, why have an economic cost-benefit study at all if every square peg has to fit into the round hole of “co-equal goals”? And if it doesn’t fit, then some contrivance such as “regulatory assurance” must be invented to make it fit.

‘Regulatory Assurance’

Both the Delta tunnel and ecosystem rehabilitation would probably be funded with a revenue bond paid for those who would use the water (rather than a statewide general obligation bond tapping the state general fund). A revenue bond would pay for the Delta ecosystem upgrades and tunnel by raising water rates for farmers and cities. This is why the Delta Reform Law has “co-equal” goals. There must be “co-equal” goals for a) Delta conservationists and b) Central Valley farmers and Southern California cities. The Delta would supply the habitat and the water; the farmers and the cities would supply most of the revenue.

To provide the revenue, however, farmers and cities have demanded “regulatory assurance.” “Regulatory assurance” is a bureaucratic term meaning that water deliveries to farmers would not be interrupted or cut back by environmental lawsuits or surprise water shut offs to save some threatened species. Farmers need assurance that their water supplies won’t be cut back over the term of any agricultural loans. And Southern California cities need the assurance of water deliveries before they invest further in water conservation. Cities surrounding the Delta may also need greater assurance if they are to be forced to pay to clean up Delta water pollution due to urban runoff.

But is ‘regulatory assurance’ a ploy?

Michael says that “regulatory assurance” has emerged as a fictional device to make the tunnel project seem economically feasible.

Economist David Sunding says that, to make the tunnel project feasible, an $11 billion value has been assigned to “regulatory assurance” to close the gap between costs and benefits.

Michael suggests that it would be less costly if the Delta Tunnels were dropped from consideration altogether and the $4 billion ecosystem restoration costs were completed separately and reduced to $2 billion. As Michael puts it:

“The BDCP envisions $4 billion in habitat investments paid for by federal and state taxpayers. So my question is: ‘could a similar $4 billion investments in habitat in a “no conveyance” alternative merit a comparable regulatory assurance from the Fish and Wildlife Service? What about $2 billion?’”

But if ecosystem rehabilitation were funded separately, there would no longer be “co-equal” goals. It would be back to Northern California wanting to fund only Delta ecosystem rehabilitation and farmers — and Southern California cities only wanting to fund a tunnel for greater reliability of water deliveries in dry years. And who would pay for stand-alone ecosystem rehabilitation if the state and federal governments are both broke?

But stand-alone ecosystem rehabilitation would lower costs even if it didn’t produce greater reliability of water deliveries to farmers and cities. But then would the project unravel politically?

Of course, if the ecosystem rehabilitation costs were lowered to, say, $2 billion, perhaps it could be funded regionally instead of statewide.

But then we’re back to the problem of what to do about the thin water storage in the state. California has already popped for $18.7 billion in water bonds since 2000 that haven’t developed any added water storage. These water bond projects may have been intended as a way to pre-mitigate the impacts of the Delta tunnel, mostly to Northern Californians.

The cost-benefit studies of the Delta tunnel/ecosystem rehabilitation do not consider these prior water bonds. Nor does it consider the cost of removing dams along the Klamath River in Oregon and Northern California to restore salmon runs as part of the costs or benefits.

To fund or not to fund, that is the question

Michael’s question — “Should the Tunnels be funded at all?” — should include whether the Delta habitat rehabilitation funding should be continued as well.

Slow population growth is another issue that Michael has perceptively raised.

California’s slow 0.6 percent average annual population growth over the past five years — the slowest in more than 200 years — may not be a short-term trend. California needs to be reminded of what happened when the Washington Public Power Supply System planned to build five nuclear power plants in the 1970’s and 1980’s. By 1983, some of the projects were cancelled due to a lack of population growth and poor management. WPPSS ended up defaulting on the bonds and went bankrupt — WHOOPS!

Gov. Jerry Brown wants a massive Delta tunnel and ecosystem rehabilitation project. Brown has delayed a vote on the $11 billion proposed state water bond until the 2014 election. But that bond has no funding for the Delta tunnel or ecosystem in it. It’s another “waterless” water bond going down the proverbial drain. Maybe Brown was right long ago when he embraced a “small is beautiful” political philosophy?

The only hypothetical economically feasible way to get more reliable water supplies to Southern California might be in tanker cars on the proposed bullet train.

Related Articles

Will Warren Buffett’s hydro prevent CA electricity crisis? — Part 1

This is the first of two articles. Part 2 is here. California is trying to create what officially is called

U.N. and CA environmental activists push agendas

April 1, 2013 By Warren Duffy In 2009, President Obama was preparing to attend a U.N. Conference in Copenhagen. The

State injects millions of new patients into ailing Medi-Cal

Nov. 20, 2012 By Dave Roberts California’s Medi-Cal managed care programs have an abysmal track record. So, naturally, state officials