Would another Burns-Porter Act resolve the Delta revuelta?

By Wayne Lusvardi

Mark Twain wrote, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” California is replaying its original political power struggle for passage of the State Water Project that had to be resolved by the Burns-Porter Act of 1955 and the Delta Protection Act of 1959.

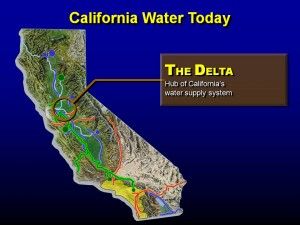

The recent reaction by Northern California against California’s proposed Bay-Delta Conservation Plan might be called a “Delta revuelta.” A revuelta is organized opposition or a conflict in which one faction tries to wrest control from another.

The current revuelta, however, is odd since no vote of the electorate or Legislature is needed to proceed with the Twin Tunnels component of the Delta Plan. Without a vote, there is no political legitimacy to undertake the Plan. A statewide vote for the California Water Bond on the 2014 ballot is only needed to fund the fish habitat restoration component of the plan.

Engineering fix for regulatory problem

The Bay Delta Conservation Plan would bring no extra water for Central Valley farmers or Southern California cities. As Steven Greenhut describes the project, it is an engineering fix for a political and regulatory problem. Water deliveries to farmers and cities have been shut down for frivolous lawsuits to protect freshwater fish. Ninety-three percent of these fish end up eaten by predator fish anyway. Instead of fixing this regulatory overkill problem, a $25 billion entire re-engineering of the Delta is being sought. Thus, there is no public legitimacy for the project based on either cost or fish habitat restoration.

The unacknowledged problem is one of political legitimacy — the justification of authority not by coercion, but by consent — that is, consent by the people, or by a substitute consensus of legislators, the governor and the courts. The central problem of the Bay Delta Plan is that it has vainly sought legitimacy by regulatory, scientific, legislative and judicial authority.

How did original State Water Project gain legitimacy?

Since history is repetitive, how did the original construction of the State Water Project in the late 1950s find sufficient political legitimacy to proceed?

Just as today, the costs and engineering feasibility were contentious. Dividing lines were drawn between North and South. Both opposed the project. Northerners felt the State Water Project was a water grab despite the County of Origin Statute of 1931 protecting their water demands. Delta and Bay area communities wanted their waterways, levees and sunken Delta islands protected.

Southerners didn’t want to pay the greatest share of the cost without guarantees of a certain allocation of water and controls over costs. Delta farmers were the clearest supporters of the project. Unions and engineers joined them. But small farmers wanted an acreage irrigation limit to protect family farms.

An attempt at an amendment to the California Constitution to protect every major stakeholder interest failed. Finally, the state legislature came up with the Burns-Porter Act as a way to reconcile the differences. The Act was named after Fresno Assemblyman Hugh Burns and Compton Assemblyman Carley Porter, who chaired the Assembly’s water committee at the time. Both were Democrats.

A part of the package of laws that made up the Burns-Porter Act was the Davis-Grunsky Act that assured Northern counties the water and money to build future projects. The Burns-Porter Act confirmed the County of Origin and Watershed of Origin Acts. Northerners were concerned that the contractual amount of water the Southern part of the state would get would be open-ended. Southerners got the assurances they wanted of a firm water allocation enshrined in the state constitution and funds specified only for projects in the Act.

The Delta Protection Act of 1959 promised adequate water and water quality for Delta users.

To increase public legitimacy, an engineering firm and a financial firm were brought in to review the feasibility of the project. They cut costs because of a concern that future monetary inflation would reduce the purchasing power of the bonds.

The Burns-Porter Act, Proposition 1, was placed on the ballot and narrowly passed in 1959 by 3 percentage points of the voters. It not only found political legitimacy but it maintained it by controlling costs.

State Water Project had NO cost overruns

According to the Department of Water Resources Financial Statements for 2012, of the $1.75 billion of general obligation bonding authorized for the State Water Project, only $1.58 billion were issued up to 2012. Only $362 million remained unpaid as of the end of the 2012 fiscal year. Despite the public’s current outcry that a doubling of costs are inevitable for the new Bay-Delta Plan, there were no cost overruns in the initial State Water Project. And there was only $2,427,356 in unpaid revenue bonds for State Water Project hydropower plants as of 2012.

Do Burns-Porter and Rendon-Bigelow Rhyme?

The modern-day counterparts to former Assemblymen Burns and Porter are Assemblymen Anthony Rendon, D-Lakewood, and Franklin E. Bigelow, R-Madera County, who respectively are chair and vice-chair of the Assembly Water, Parks and Wildlife Committee. Rendon has a PhD from U.C. Riverside. Bigelow is a former Vice-President of Ponderosa Telephone Company and was a Madera County Supervisor.

California will be lucky if history not only repeats itself with no cost overruns for the proposed Bay-Delta Twin Tunnels project. But it will be really lucky if the project finds any political legitimacy even if Assemblymen Rendon and Bigelow change their names to rhyme with Burns and Porter. Otherwise, Delta will still rhyme with revuelta.

Related Articles

Wired is "tired"on Cali mass transit

Wired magazine runs a “wired/tired” feature, in which they judge new technologies as being “wired” — up-to-date, hip, cool, etc.

Is there ever any positive news about the bullet train?

April 4, 2013 By Chris Reed Is there ever any hard, legit good news about the California High-Speed Rail Authority’s

AG Kamala Harris ensures she won't go down with bullet-train Titanic

The saga of the California bullet train took a twist on Friday that at first seems strange but at second