Justice Brandeis brings light to U.S., CA privacy controversies

LOS ANGELES — Revelations about the federal government’s data mining through PRISM, the clandestine electronic surveillance program operated by the National Security Agency, have prompted a debate about possible government overreach and intrusion. The question about privacy is hardly new, but as we continue to create a de-facto surveillance society through every online purchase and Twitter post, intrusion has only become easier and expected.

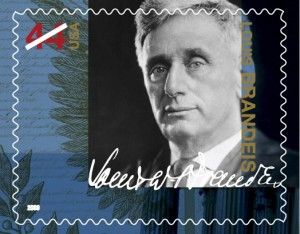

In 1890 Louis Brandeis, a future Supreme Court justice, and Boston attorney Samuel Warren published an article, “The Right to Privacy,” in which they argued U.S. law should recognize privacy as a right and impose liability for violations of privacy. Brandeis and Warren, who decried the “yellow journalism” of the day, found much support because the public was learning to cope with new forms of technology. In a passage sounding as if it were written today, they explained:

“Now that modern devices afford abundant opportunities for the perpetration of such wrongs without any participation by the injured party, the protection granted by the law must be placed upon a broader foundation.”

An explicit right to “privacy” does not actually appear in the U.S. Constitution. There are, however, clear constitutional limits to intrusion into a person’s right to privacy.

The Fourth Amendment of the Constitution guarantees:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

Due to Supreme Court recognition, the Fourteenth Amendment also provides considerable due process right to privacy.

Trade secrets

The Supreme Court also recognizes rights in trade secrets and non-published literary materials, irrespective of whether or not those rights are intentionally or unintentionally infringed upon. Further, the court has no regard for the value these materials may have.

Brandeis and Warren contend that the recognition of this right stems from the protection of a private individual’s “thoughts, sentiments, and emotions, expressed through the medium of writing or of the arts.” These items are described as private diaries or letters that need protection from unwarranted searches. The authors quote a Supreme Court case that considers a violation of privacy on these items to be a “breach of confidence” and an “implied contract.” In other words, individuals who send letters have an expectation that the letters will remain private.

The Supreme Court also defines violation of this idea as a breach of trust, because one person has trusted another not to publish private writings, pictures, or art, without their consent. The court, the authors write, attempts to protect an individual from having “facts relating to his private life, which he has seen fit to keep private” published by another, whether for personal gain or another intention.

As early as 1834, the United States Supreme Court is quoted recognizing that a “defendant asks nothing — wants nothing, but to be let alone until it can be shown that he has violated the rights of another.” This idea is paraphrased as “the right to be let alone.”

Louis Brandeis also used the phrase “the right to be let alone” in his famous dissent in Olmstead vs. U.S. in 1928, the first wiretapping case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled in favor of the government in the wiretapping case, but proponents who claim a right to privacy from the government or other entities cite the “right to be let alone” till this day. U.S. Supreme Court decisions, moreover, show that this phrase has come to be associated specifically with preventing the government from invading privacy.

Modern rulings

Modern court rulings have not always abided by these rights. One such court ruling in 1983 permitted police, without a warrant, to plant a tracking device on a person suspected of drug possession to track the suspect without his knowledge. Courts today use the ruling, United States vs. Knotts, as a precedent to lend credibility to unwarranted GPS tracking. A suspect, therefore, does not have a recognized right to privacy in his or her car.

New electronic surveillance technologies over the last century have greatly reduced a person’s “right to be let alone.” Pervasive societal use of video surveillance technologies has virtually eliminated the expectation of privacy in many public locations, while video surveillance systems in private spaces continue to encroach upon rights. Consider, for instance, that some states will record individuals in a clothing store fitting room (to prevent thefts).

In the United States today, “invasion of privacy” is often a basis for court cases and legal pleadings. Modern tort law illustrates four categories that encompass the notion of privacy invasion:

* Intrusion of solitude: physical or electronic intrusion into one’s private quarters.

* Public disclosure of private facts: the dissemination of truthful private information that a reasonable person would find objectionable.

* False light: the publication of facts that place a person in a false light, even though the facts themselves may not be defamatory.

* Appropriation: the unauthorized use of a person’s name or likeness to obtain some benefits.

California privacy

The good news is that some states explicitly recognize privacy. California is among these states. For instance, Article 1, Section 1 of the California Constitution describes privacy as an “inalienable right.” California’s SB 1386 goes further to guarantee that, if a corporation exposes a California resident’s information, this exposure must be reported to the citizen. Other states, such as Montana, have come up with similar measures in the privacy protection arena.

However, the state’s acknowledgement of privacy can only go so far.

On May 9, a California district court dismissed with prejudice a complaint against Delta Air Lines filed by California Attorney General Kamala Harris that alleged violations of the California Online Privacy Protection Act. The case, concerning Delta’s mobile app, was dismissed due in large part to the federal Airline Deregulation Act, which preempts Delta from adhering to California’s privacy law because the app constitutes a “service” that “is related to price, route, or service of an air carrier.”

California continues to pursue privacy policies, especially with wearable computers (particularly with regard to mobile apps). In January, Harris issued guidance on expectations of privacy from mobile applications.

But, as made clear the in the case with Delta, there are exemptions.

New threats

New threats

The new threat to privacy is going to be linked to wearable computers or devices carried on one’s person, such as Google’s Glass. These technologies constantly record and store information. Currently, there are no statutes or decisions directly regulating a wearable computer’s intrusion into personal privacy rights.

Brandeis and Warren called for new laws to catch up with new forms of technology and their infringement on privacy in the 1890s. More than 100 years later, the same concerns remain. Computers, mobile phones, online applications and CCTV cameras are just a few of the widespread technological innovations that raise questions about privacy.

Most phones boast touch display menus, wireless Internet dating networks, GPS sensors, voice recognizers and cameras. There are no laws that prevent companies from sharing information about a person’s browsing habits, telephone calls and locations.

Rory Cohen is an award-winning Los Angeles-based journalist and the assistant deputy editor of the Commentary section at the Orange County Register. Her work has been published with the Register, The Guardian, KCET and the Scientific American.

Related Articles

CA Democrats challenge Lt. Governor Newsom on gun control

Seeking to bolster his early-bird campaign for governor, Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom forged ahead with a controversial ballot initiative

Driver’s license bill races through Legislature

April 23, 2013 By Katy Grimes SACRAMENTO — Driver’s licenses for illegal immigrants is back on the table and making

Hillary's July 4 conversion

Steven Greenhut: Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, during her tour of Eastern Europe, warned, “[W]e must be wary of the