Underappreciated Prop. 13 fact: It protects vulnerable in housing bubbles

As the push builds in Sacramento to undercut Proposition 13 by weakening its limits on how fast business property taxes can increase, it’s worth making two basic points in defense of the 1978 initiative — one of which doesn’t get the attention it deserves even from fans of Howard Jarvis’ measure.

As the push builds in Sacramento to undercut Proposition 13 by weakening its limits on how fast business property taxes can increase, it’s worth making two basic points in defense of the 1978 initiative — one of which doesn’t get the attention it deserves even from fans of Howard Jarvis’ measure.

The first has to do with its allegedly devastating effect on revenue.

It didn’t turn off spigot

There’s something about Proposition 13 that induces derangement among the political and media establishment in California. You can make an argument, as Joe Mathews has, that using direct democracy to shape key state policies is a formula for straitjacketed government. But then the argument should apply to lots and lots of props, not just 13, starting with 1988’s Proposition 98, which made permanent teachers unions’ dominance of state spending and budget decisions. Why should one result of direct democracy bear the blame for other exercises in direct democracy?

But to argue that capping one source of taxes has ruined the state, as the Peter Schrags and the George Skeltons of the world like to do, is bizarre. By any measure, tax revenue in California has gone up far faster than inflation plus population growth since Prop 13’s adoption in 1978. By any measure, California has among the nation’s highest sales, income and gasoline taxes and the highest corporate taxes in the West. Only in property taxes are we in the middle of the 50 states.

We have enough to live within our means. The only reason it sometimes seems like we do not is because of political decisions that place the interests of public employees ahead of the interests of the public, in pay, benefits, job protections and more.

This is pretty well understood among libertarians, conservatives and small-government advocates.

Not just about limiting taxes; it’s about protecting homeowners

But the second grounds for offering a vigorous defense of Prop 13 is often not appreciated enough by people across the California political spectrum — including its admirers. The measure was drafted and passed in a landslide for a very specific and powerful reason: to protect people from losing their homes or suffering financial disaster because of housing bubbles.

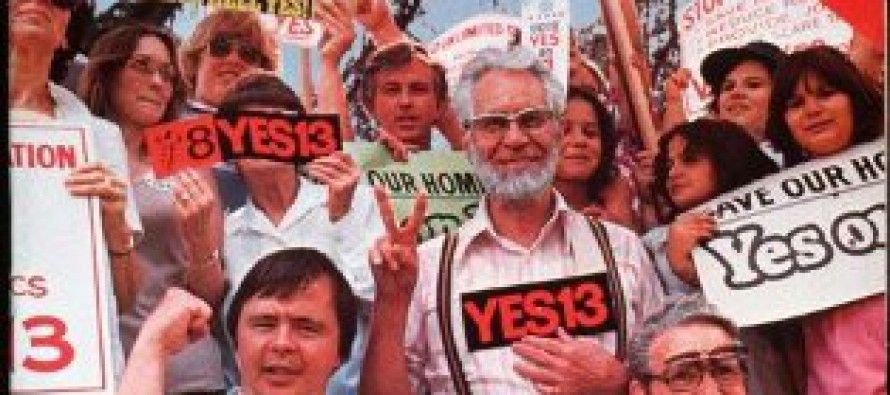

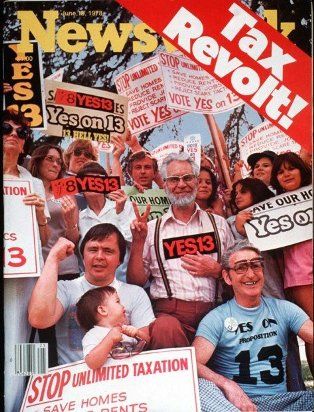

This is from a June 5, 1978, Newsweek story about the mood in California on the eve of Prop. 13’s adoption:

“Shaken homeowners and landlords wobbled out of the country assessor’s office in Los Angeles last week with rebellion in their eyes. In the suburb of Palos Verdes, Don Johnson, a certified public accountant who earns $25,000 a year, returned dumbstruck to his four-bedroom ranch home. When he and his wife, Ellen Ann, bought the home in 1959 — for $33,900 — their tax bill was $600 a year. But inflation ballooned the assessed value of the home, and by last year, the Johnsons’ taxes were $1,593. Last week, the tax man released the latest listings. Overnight the assessed value of the Johnson home has soared to $135,000 and the Johnsons’ taxes threatened to skyrocket to $4,139.

“At the assessor’s office in West Los Angeles, an ashen-faced husband emerged to give similar bad news to his wife, a woman in a matronly blue dress. ‘Sam, Sam, don’t tell me,’ she cried. ‘I’m going to have a heart attack right here.'”

Why can’t members of the political-media establishment (including occasional contrarians Joe Mathews and Dan Walters) grasp that we’d have seen a wave of such stories during the housing bubble from 1998 to 2006 without Proposition 13?

Home prices in some markets nearly tripled over that span.

Retirees, those living on fixed incomes and middle-class families with big mortgages would have been devastated if their property taxes had nearly tripled. We’re talking about millions of people.

So while we are used to seeing Prop. 13 as an artifact from a distant era, we don’t realize it remains an enormous protection TODAY for current homeowners who can barely make ends meet and who would be ravaged by a huge tax hike.

This may not be central to the fight over whether businesses should be exempt from Prop 13’s caps on how fast property taxes can increase. But it should be central to the broad debate over whether Prop 13 is bad or good for California. During the latest housing bubble, as in all the housing bubbles that preceded it, Prop 13 did far more to protect regular Californians from financial disaster than any other single factor.

That should matter much more than it seems to.

Related Articles

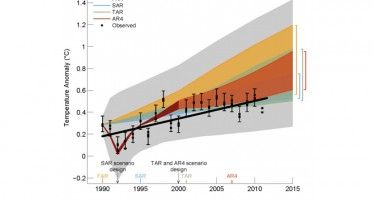

Now UN says global warming exaggerated

On our site and elsewhere, global warming/climate change defenders say almost 100 percent of “climate scientists” maintain global warming/climate change

Do you think you are free?

Aug. 9, 2012 By John Seiler With inflation gearing up again, there’s one safe way to protect your money that’s

Sale of State Properties On Hold

Katy Grimes: Finally someone is listening — the sale of the 11 state properties appears to be finally off, at