$5 gas in CA? Lack of cap-and-trade price ceiling could bring it

At its October 24-25 board meeting, the California Air Resources Board will reconsider its “Market Based Compliance Mechanisms,” meaning its cap-and-trade program. The program “caps” greenhouse emissions, and has “traded” them in quarterly auctions over the past year.

At its October 24-25 board meeting, the California Air Resources Board will reconsider its “Market Based Compliance Mechanisms,” meaning its cap-and-trade program. The program “caps” greenhouse emissions, and has “traded” them in quarterly auctions over the past year.

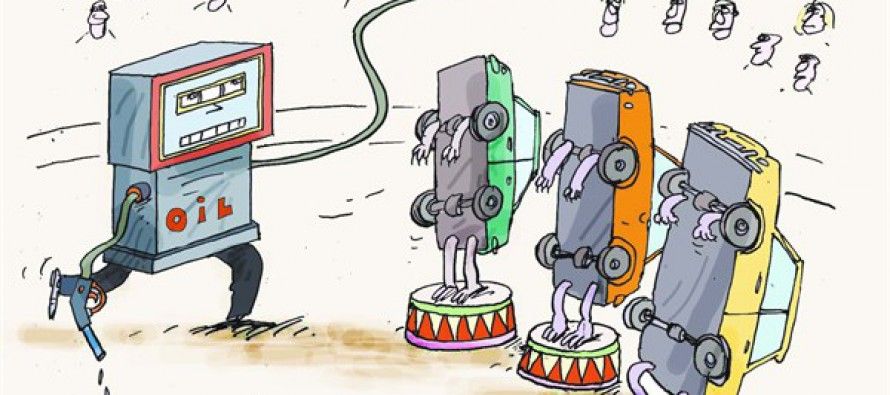

But many Californians would be disturbed to learn that the cap-and-trade program has no cap on prices for industries to buy emissions allowances. Cap and trade puts a cap on emissions but not on prices. Californians would be even more concerned to learn that with no price cap, gasoline prices could rise by over $1 per gallon, to more than $5 a gallon in California; and the stock prices of oil companies could nosedive.

Because of this risk, Severin Borenstein of the UC Berkeley Energy Institute is calling for a “hard price cap” to be placed on bid prices for emission permits. Borenstein’s warning of a need for a price cap has been echoed by Robert N. Stavins of Harvard University and Todd Schatzki of the Analysis Group, economic financial consultants in Los Angeles.

Cap and trade works by creating a scarcity of permits

Cap and trade is a tax on air pollution that is not called a tax but an “emissions allowance or permit.” Cap and trade is a heavily regulated pollution tax market. Cap and trade does not work like obtaining a building or business permit from a city. It works by creating a scarcity of pollution permits and having large oil companies, regulated utilities and municipal utilities bid on them. As California’s cap-and-trade program continues, the number of permits will be reduced each year to compel polluters to reduce emissions, buy offsets, or be forced to pay enormous prices to pollute.

California’s program will increase its emission cap in 2015, when it expands to include municipal utilities and wholesale water agencies. Thereafter, the cap will be reduced about 3 percent each year until 2020, when the cap is expected to be 15 percent lower than the 2012 level.

Without choice, there is no such thing as a market. Where limited choice enters the cap-and-trade program is by allowing polluters to reduce emissions or buy an “offset” instead of a permit. Instead of reducing its own pollution, a company or utility can purchase an “offset” certificate from an independent organization that uses the money to fund a reduction of C02 somewhere else. For example, Southern California Edison could buy an offset by funding the reforestation of areas burned by California’s Rim Fire.

California allows only 8 percent of a company’s or utility’s compliance requirements to be offset by three different types of offsets: expansion of forests and urban forests, methane capture on farms and ranches and the reduction of ozone depleting substances. CARB just began to allow offsets in September.

A problem arises, however, if there is an economic boom resulting in greater pollution, higher costs to abate or control pollution, or offsetting organizations charge holdout prices. CARB’s emission allowance auction “floor price” in 2013 has been about $10 per ton.

Borenstein says it is generally recognized that California could not continue its cap-and-trade program if the price climbed to about $50 per metric ton of C02 in 2013 (then rising 5 percent per year for inflation). Under certain adverse scenarios, pollution allowance prices could increase from $21 to $106 per metric ton (MT) of carbon dioxide emitted. According to Borenstein, an emissions allowance price of $50 per MT would increase gasoline prices about 50 cents per gallon. Raising allowances over $100 per MT could result in gasoline prices rising over $1 per gallon.

CARB contains prices with reserve allowances

The way CARB currently curbs auction prices is by its “Reserve Policy.” CARB can flood the market with extra allowances in an emergency so that the supply of permits exceeds the demand and, thus, prices would fall.

However, as Stavins points out:

“Nevertheless, the possibility remains that as a result of unanticipated changes in the market (such as higher than anticipated economic growth in California, slower diffusion than anticipated of low-cost abatement technologies, etc.), the current reserve structure could lead to excessively high allowance prices if the reserve is exhausted.”

Borenstein recognizes another insidious problem of not putting a cap on cap-and-trade auction prices per ton of pollution: market uncertainty. As he puts it:

“Market participants can only speculate at how the state would put the brakes on an allowance market with skyrocketing prices. And that’s part of the problem. Regulatory uncertainty undermines market credibility, especially in times of extreme outcomes.”

We can’t know with certainty how fast the economy will grow. And often accurate data on economic growth take years to produce.

Borenstein acknowledges the probability of an emergency scenario could be 10 percent or more. But such low odds were also prevalent during the California Energy Crisis of 2001 and the recent “Black Swan” event of the Mortgage Meltdown and Banking Crisis of 2008.

CARB has recognized that there is no price containment within its auction rules. It has proposed staggering permit allowances from prior years to be shifted to earlier years if prices got too high. One cap-and-trade market participant described this proposed system as “trying to fill a bathtub by taking water from one end of the tub and pouring it into the other.” Borenstein writes that CARB’s proposal isn’t enough to protect against a 2001 Energy Crisis-type scenario:

“While the proposed changes are a small step in the right direction, they don’t go far enough to address the fundamental risk to the market from a surge in emissions that could cause the price of allowances to skyrocket.”

Cap-and-trade advocates claim that setting a price ceiling, as Borenstein advocates, would ruin the “environmental integrity of the program.” But Borenstein says that there would be no impact if prices stayed below the price ceiling. And if government has to “step in” during an emergency, then “environmental integrity” would be lost anyway.

CARB amendments not enough

As mentioned, at its October board meeting CARB will reconsider its “Market Based Compliance Mechanisms.” Economists like Borenstein, Stavins and Schatzki are warning that CARB needs to put a price cap into cap and trade.

Borenstein indicates this is not just a concern of big oil companies and utilities. A price cap is needed to contain gasoline price spikes for all Californians and stock market crashes for investors. That includes the California Public Employees' Retirement System, which is heavily invested in petroleum-related stocks.

Editor's Note: From an earlier version, Stavins' name was corrected to “Robert.”

Related Articles

Draconian water plan unveiled

MAY 3, 2010 By SUSAN M. TRAGER Water is the lifeblood of California. Throughout the state’s history, it has formed

Good news: Lantern brings Internet to everybody

Some good news. A new pocket-sized, solar-powered device, Lantern, brings the Internet to everybody — including the poorest people who

Rail Series: Medium-speed train tracking costs less than high-speed rail

This is Part 4 of a series on Medium-Speed rail alternatives to California’s High-Speed Rail project. Click to read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part