Govt. Fights Citizens' Right to Know

By TORI RICHARDS

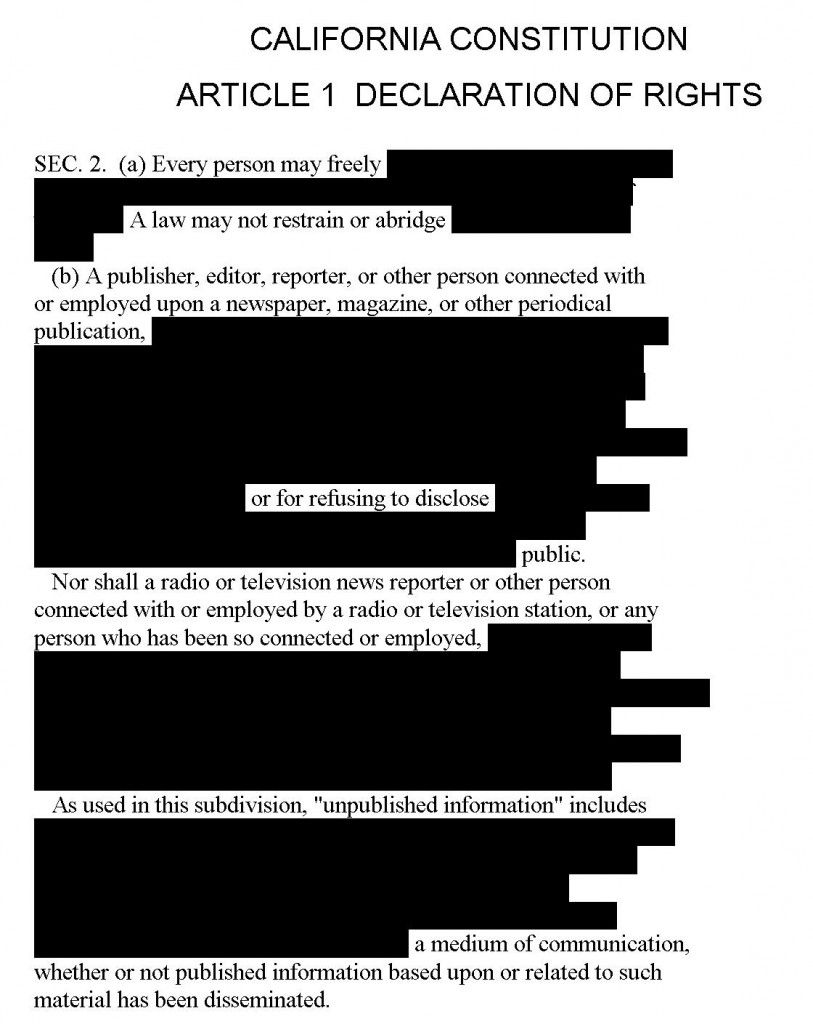

A recent appellate court decision could have far-reaching impact on whether citizens can successfully fight government agencies for documents under the California Public Records Act.

Attorneys battling for public records only have one big hammer — attorneys’ fees upon winning in court. Now this important element has been curtailed in a recent court opinion. This will make government agencies less likely to produce records in a timely manner and not fear lawsuits that would normally come out of their budgets.

Said Paul Boylan, an attorney who specializes in CPRA lawsuits:

This case in particular shows that the citizen will not be awarded fees and costs unless the citizen can affirmatively and definitively prove that the governmental agency delayed or withheld information in bad faith — an evidentiary burden that a citizen is unlikely to be able to meet.

In the face of such a daunting burden of proof, no attorney will agree to represent a citizen in such a case unless they receive payment up front, and very few common people can afford what it would cost. And that means that governmental agencies can violate the CPRA without fear of being ordered to pay a petitioner’s fees and costs if they make it look like they were acting in good faith — which is easy to do and hard to disprove.

The California Public Records Act clearly spells out the legal right to obtaining government records. In reality, it often takes a lawsuit to enforce this.

“Ordinary citizens and most media outlets don’t have the legal expertise and resources to fight these types of cases,” said Chris Farrell, a director at Judicial Watch, which fights government waste. “The government routinely stalls record releases for months and years, and engages in procedural gamesmanship as techniques to jack up legal fees and discourage requesters.

No doubt about it, attaining public records is a rich man’s endeavor. Government agencies often drag cases out for years, leaving requesters with no other option than suing. Delays equal money as the two parties spend endless hours in court arguing over what is public and what is not. This racks up attorney fees unaffordable to most citizens and many media outlets.

“There is an incredible range of response time with [California] government agencies,” said attorney Roger Myers, a partner with Holm Roberts & Owen and legal counsel for the First Amendment Coalition, a watchdog group. “Some are very responsive, others are not and you don’t get anything unless you pester, holler, and scream.”

Crews v. City of Willows

In the decision Crews v. City of Willows, filed Nov. 23, 2010, the California 3rd District Court of Appeal carved out an exception that isn’t specifically detailed in the language of the CPRA. But the opinion is not published, meaning it is non-binding statewide.

However, any judge deciding whether to award fees could be swayed by this opinion, especially if their court is within the 3rd Appellate District.

The exception allows for government agencies to produce documents after the 10-day deadline if they put forth a “good faith effort” to comply with the request during the original deadline. Agencies which have shown such an effort aren’t liable for attorneys’ fees if the requester decides to sue to enforce their demand.

The law mandates attorneys’ fees for a winning party and often the threat of having to pay such an award is the only hammer requesters have in getting compliance. But in this appellate opinion, the requester didn’t “prevail” because the government in question was planning on releasing the documents anyway.

The lawsuit stems from a 2009 request that publisher Tim Crews of the Sacramento Valley Mirror newspaper made for job applications to a government post in the rural city of Willows. The documents weren’t produced until after the paper sued. Glenn County Superior Court Judge Peter Twede refused to grant attorneys’ fees and the matter was appealed.

“In the city of Willows case, Judge Twede behaved no differently than many other judges by stretching the law to find a reason — any reason — to prevent a prevailing party from recouping their fees and costs,” said Boylan, the attorney representing the Mirror.

Boylan said Twede went out of his way to side with Willows — even making arguments on behalf of the city that its own attorney didn’t make. In the end, the judge ended up applying a California doctrine pertaining to attorneys in general cases, when he should have been looking at the language of the California Public Records Act, Boylan said.

“This is an example of a widespread and growing hostility toward those seeking to enforce the CPRA,” Boylan said.

In the underlying case, Mirror publisher Tim Crews requested applications to a Planning Commission vacancy. The city clerk provided redacted copies the following day. The clerk testified that the city attorney was not available to review the request, so out of caution she redacted the applicants’ personal information.

When the 10-day deadline passed without the release of the unredacted versions, the paper sued. The documents were released a month after the lawsuit was filed. The city told the court that the Mirror never requested unredacted versions, so they thought they had complied with the request.

The appellate court sided with Twede in a 34-page opinion, which said:

Under the unique circumstances of this case, where the undisputed evidence shows the City reasonably believed the redacted documents satisfied the request and did not know of any pending request for unredacted documents at the time the lawsuit was filed, appellant cannot claim a litigation success.

The standard test for determining whether someone has prevailed under the CPRA for purposes of recovering attorney fees is whether or not the litigation caused a previously withheld document to be released.

An Expensive Endeavor

In the end, it’s the taxpayers who lose on several fronts. If the request takes the form of a lawsuit, it’s often years before the records are relinquished, if at all. By then, the information could be of little value to the requester, especially if it involves a news story where the issue is no longer prevalent.

In normal cases, government agencies on the hook for paying the winners’ fees and also rack up expenses on their own end — all funded by taxpayers.

It’s too soon to see the impact of the Crews v. City of Willows case. Previously, the various agencies appeared to be more cautious in their appeals because they didn’t want the embarrassment of losing in an era of budget cutbacks and scrutiny, critics say.

Added Jim Ewert, legal counsel for the California Newspapers Publishers Association, added:

They are playing with Monopoly money because it’s not their money. Now that the resources are more limited, it is starting to enter their economic analysis.

The California Attorney General’s Office issued a statement saying it promptly informs requesters if a decision is made to extend the 10-day rule for compliance with the CPRA. They receive an average of 35 requests a month.

“At DOJ, we make every effort to comply with every PRA request within the statutorily prescribed time frames, regardless of requestor,” spokeswoman Debbie Mesloh said.

Half a million dollars in fees

So if the courts intervene, how much would it cost in attorneys’ fees?

“You’d be lucky to get away with only spending $10,000, and it can go up to half a million,” said Myers of the First Amendment Coalition. “To go through the first level and get a ruling from the trial court can cost $25,000 to $50,000 or more. Most are not appealed because of the risk that it could increase the fees.”

But those that are appealed have racked up some mind-boggling expenses. The First Amendment Coalition litigated a case that is believed to be California’s largest award for attorneys’ fees: $500,000. It involved a lawsuit against Santa Clara County over access to a database. The Coalition filed the case in 2006 and won on the trial level, then the county appealed and lost three years later.

Attorney Boylan had represented citizens and media organizations in public records cases on a contingency basis. He has had a wide range of awards, mostly under $100,000.

One example on the lower end of the scale is the small Northern California city of Fortuna. City officials wanted to put in a new water system and one citizen thought it wasn’t warranted and a waste of money. She requested a schematic of the city’s water system.

“They said no, on behalf of national security grounds, because terrorists would use it to bomb the water system,” Boylan said. He was awarded $21,000 in fees.

But the king of all cases is believed to be Judicial Watch’s “Chinagate” Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against the U.S. Commerce Department during the Clinton era. The organization was asking for records of illegal 1996 campaign donations that were made in exchange for disclosing military secrets to China.

Four different lawsuits ensued, spanning a decade, in which the Commerce Department was found to have destroyed evidence and falsified testimony. The defendants lost on appeal and a judge ruled in favor of Judicial Watch, ordering the Commerce Department to pay $900,000 in attorneys’ fees.

According to the watchdog groups, government agencies have figured out which requesters have a track record of suing, and that enters into the agencies’ analysis of whether or not to comply.

“If an agency knows they are dealing with a requester with a capacity to file a lawsuit and a record of doing so, they are going to be much more compliant with the law,” said Peter Scheer, director of the First Amendment Coalition.

Farrell of Judicial Watch agreed. “These agencies know who they are and they know who will sue them. They would rather not go in front of a judge and explain why they are not obeying the law,” he said. “The average citizen gets jerked around much more; they know they can grind the citizen down.”

Related Articles

Young women text while driving

Katy Grimes: OMG – do ya think? Like, that is totally wrong. The California Automobile Club announced that texting by

Trouble at Developmental Services

AUGUST 25, 2010 By ANTHONY PIGNATARO This should sound familiar to many people. “(T)here is not really any communication between

LAO: Bullet train could increase greenhouse gases by 2020

Gov. Jerry Brown’s plan to spend the lion’s share of cap-and-trade auction revenue on the high-speed rail project won’t