In San Fernando rail showdown, echoes of Chavez Ravine

In the San Fernando Valley, there’s been intense opposition for years among its 1.7 million residents to having the state’s bullet train project cut through middle-class and poor neighborhoods and equestrian areas. Civic leaders, activists and property owners view the project as bisecting the valley into two communities because of how difficult the high-speed rail line would make it to move easily from one side of the tracks to the others as it went from Palmdale to Burbank.

In the San Fernando Valley, there’s been intense opposition for years among its 1.7 million residents to having the state’s bullet train project cut through middle-class and poor neighborhoods and equestrian areas. Civic leaders, activists and property owners view the project as bisecting the valley into two communities because of how difficult the high-speed rail line would make it to move easily from one side of the tracks to the others as it went from Palmdale to Burbank.

That’s why Los Angeles County Supervisor Michael Antonovich, who represents much of the affected region, has long pushed rail officials to build a 15-mile-long tunnel under the San Gabriel Mountains for the Palmdale-Burbank link. Rail officials have agreed to consider the request, but no one familiar with the project’s finances considers that feasible because of the extreme cost. Underground rail lines built in recent years around the world cost from $400 million to $600 million per kilometer — or about $650 million to $975 million a mile. And that’s for projects that are far less daunting than tunneling through a mountain in an area of frequent seismic activity. Such a tunnel would balloon the project’s present $68 billion estimated cost.

But local opposition grew even stronger a year ago this month when state officials pushed up construction plans for the Burbank-Palmdale link. This was hailed by former Assemblyman Richard Katz, a Los Angeles Democrat, as a “game changer” that would build support for the project: “The visibility will make it real and people can see where their tax dollars are being spent.”

Elected officials lead furious protest

The decision may indeed have been a “game changer” — but not in the way Katz expected. At a raucous community hearing last week in the city of San Fernando, rail authority officials were overwhelmed by the vehemence of community opposition. This is from the Los Angeles Times:

Protestors … took over an open house meeting held by the California High-Speed Rail Authority. They demanded that state officials answer questions about the project’s impact on their community.

But unlike typical protests, this one was led by elected officials. Seventy people, headed by the city’s mayor pro tem and other current and former city officials, marched into a city auditorium and set up their own public address system.

With their Police Department on hand, they confronted state officials with anger that has not been seen even in the virulent opposition to the project in Northern California or the Central Valley.

“The bottom line is you are not really welcome,” Mayor Pro Tem Sylvia Ballin told state officials, whose plans call for bisecting the small working-class city with high sound walls that the city fears will become an eyesore and magnet for graffiti.

“We will lose in the city $1.3 million annually as a result of your brilliant planning,” she said, referring to projected losses of tax revenue when businesses shut down. “We are here to tell you we will not accept it quietly, not one bit.” …

Protesters rip refusal to answer questions

San Fernando Valley residents’ objections went far beyond the California High-Speed Rail Authority’s plans.

Stunned state officials stood stone-faced at the protest, refusing to answer questions that Ballin and other city officials and residents asked.

“The route would destroy this community, splitting it north to south,” City Manager Brian Saeki said in an interview. …

Protesters said they would not accept the state’s way of conducting meetings on the project, which includes refusing to allow residents to ask questions during an open forum.

“We say no,” San Fernando Councilman Jaime Soto told state officials from his microphone. “This is not your regular meeting. You are a guest here.”

‘You are not going to displace our families’

The intensity of the opposition isn’t the only factor that Gov. Jerry Brown, the California High-Speed Rail Authority and the trade unions backing the project have to fear. It’s the likelihood that this fight will be framed as David vs. Goliath — specifically Latino David vs. white, establishment Goliath. The cities of San Fernando and Pacoima have been hotbeds of the most intense opposition to the project. San Fernando is nearly 90 percent Latino; Pacoima is 86 percent Latino. Activists like Xanaro Ayala characterize the fight as being a continuation of the indignities Latinos have faced: “We have seen this before when they’ve built the freeways and divided up our community. We are saying, “[No to the state government], you are not going to displace our families,” he said at the rail authority open house.

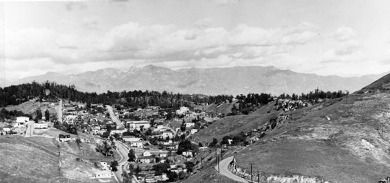

This framing and rhetoric touches on an open wound in Los Angeles’ civic history: What happened in the 1950s some 20 miles southeast of San Fernando in the then-semi-rural Chavez Ravine community, a scenic area of rolling hills just south of Elysian Park. Beginning in 1950, the city started using eminent domain to clear out the 1,000 mostly Latino families in the community to allow construction of a federal public housing project, with promises that they would have the first chance to move into the new units when they were built.

This framing and rhetoric touches on an open wound in Los Angeles’ civic history: What happened in the 1950s some 20 miles southeast of San Fernando in the then-semi-rural Chavez Ravine community, a scenic area of rolling hills just south of Elysian Park. Beginning in 1950, the city started using eminent domain to clear out the 1,000 mostly Latino families in the community to allow construction of a federal public housing project, with promises that they would have the first chance to move into the new units when they were built.

But in 1958, the Dodgers moved from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, and team owner Walter O’Malley thought Chavez Ravine was an ideal site for a new baseball stadium. This led L.A. officials to renege on their promise of a public housing project with homes for displaced Latino families, clearing the way for the construction and then the 1962 opening of Dodgers Stadium — prompting years of bitter protests and creating what is widely seen as one of the darkest chapters in L.A. history.

This history is likely to be invoked regularly by residents of San Fernando, Pacoima and other mostly Latino communities in fighting a state project that they believe would destroy their way of life.

Chris Reed

Chris Reed is a regular contributor to Cal Watchdog. Reed is an editorial writer for U-T San Diego. Before joining the U-T in July 2005, he was the opinion-page columns editor and wrote the featured weekly Unspin column for The Orange County Register. Reed was on the national board of the Association of Opinion Page Editors from 2003-2005. From 2000 to 2005, Reed made more than 100 appearances as a featured news analyst on Los Angeles-area National Public Radio affiliate KPCC-FM. From 1990 to 1998, Reed was an editor, metro columnist and film critic at the Inland Valley Daily Bulletin in Ontario. Reed has a political science degree from the University of Hawaii (Hilo campus), where he edited the student newspaper, the Vulcan News, his senior year. He is on Twitter: @chrisreed99.

Related Articles

High speed rail slows down

APRIL 30, 2010 Is it possible that the push for high speed rail in California could be slowing down? Recent

Filner’s fate: The warring conventional wisdoms

There are two conventional wisdoms about Bob Filner, San Diego’s embattled pervert of a mayor, and they can’t both be

Death Row Loses Another Inmate

Anthony Pignataro: Well, another condemned prisoner has died on California’s notorious Death Row. Not by execution — don’t be silly